LACMA’s Decorative Arts and Design Acquisitions Committee (DA²) held its seventh annual meeting in May. Working with the department’s curators, DA² supports the acquisition of outstanding examples of decorative arts and design for the museum’s permanent collection. This year’s meeting was a huge success, and all of the objects presented were acquired! Through the group’s generosity, LACMA was able to add exciting objects in some of our strategic collecting areas, including California furnishings, craft, and graphic design, as well as international modern and contemporary design.

This vase was made at the Arabia factory, the most famous and prolific ceramics manufacturer in Finland. It was part of a line that featured several different forms, all of which were characterized by stylized geometries and a nature-inspired color palette. While the designer of these pieces is unrecorded, many of the patterns came from a series of booklets on Karelian ornament entitled Suomalainen ornamentiikki (Finnish Ornament) that were published by Arabia designer Johan Jacob Ahrenberg from 1878 to 1882 (Karelia was an eastern province of Finland, now part of Russia, regarded as the repository of all that was essentially Finnish). The piece thus represents an effort to visualize Finnish national identity at a time when the country was asserting independence from Russia.

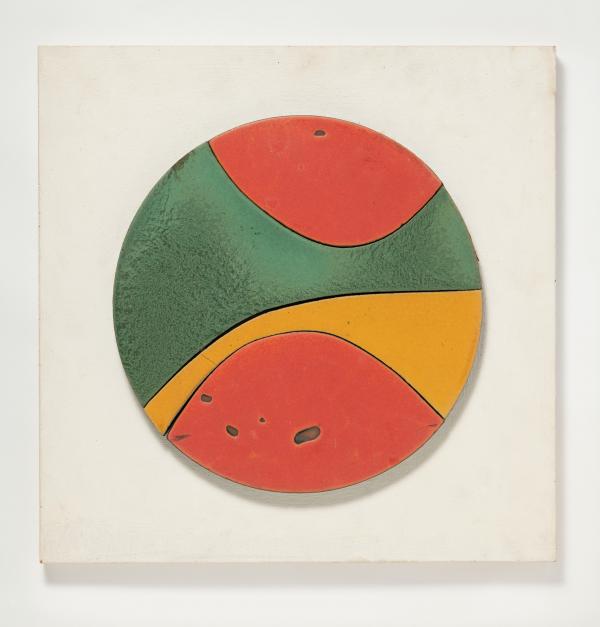

Doyle Lane was a studio ceramist and artist whose work ranged from vessels to large-scale murals. LACMA was able to acquire 11 works that demonstrate Lane’s range in scale, form, and glaze. Lane is known for his wide variety of glazes, many of which are represented in this group. He often manipulated the surface of the clay, creating alluring patterns and gestural effects. Lane also made clay paintings, applying glaze to clay slabs fired under high temperatures that resulted in vivid color combinations and textured surfaces (see top image above). As an African American craftsman working in Los Angeles in the mid-20th century, Lane’s artistic opportunities were often limited—he could not show in the mainstream galleries and did not have access to influential collectors. However, he prevailed over these obstacles, focusing on architectural commissions and producing work like this for exhibitions.

The geometric simplicity of Marcel Breuer’s B5 side chair makes it a quintessential example of Bauhaus design. Breuer became interested in tubular metal as a material for furniture after observing its strength and durability on the bicycle that he rode around the Bauhaus, the avant-garde German art school. The B5 chair demonstrates Breuer’s mastery of orthogonal form while preserving subtle visual detail, such as the parallel front stretchers and rhyming handle and seat. Its simple geometries of a cubic base and perpendicular planes of fabric show how Breuer simplified the chair to its barest minimum.

.jpg)

Spurred by architect Marcel Breuer’s comment that he could not find a single well-designed floor or table lamp for his Exhibition House at the Museum of Modern Art in 1949, MoMA sponsored a lighting design competition the following year. Works by 15 of the winners were included in a "New Lamps" exhibition from March to June, 1951. In collaboration with MoMA, the manufacturer Yasha Heifetz co-sponsored this national competition, and then put 10 of the prize-winning lamps into production.

A lamp by Zahara Schatz and one by A.W. and Marion Geller were two of the lamps sold at progressive design stores throughout the country. We are fortunate to add them to the collection, since lamps from this seminal "good design" project rarely survive in such excellent condition.

This rug and pouf provide an outstanding example of Tejo Remy and René Veenhuizen’s ethos and practice of incorporating “upcycled” materials. It was designed in collaboration with Remy’s wife, the site-specific artist Tanja Smeets. In 2008, the three were commissioned by a foundation in their native Netherlands to create a more pleasant environment for children being treated for epilepsy at the Hans Berger Clinic in Oosterhout. As Smeets explains, they created colorful rugs because: "To minimize the effects of an epileptic fit, you need warmth and softness: an environment with rounded forms and lots of places to sit and lie down. We chose used wool blankets as our basic material.” This solution to the problem of a cold and sterile environment was enthusiastically received not only by the patients and their families, but also by people responding to the intimacy and sheer joy the design invokes and has resulted in many other commissions for the rugs, including the one purchased for LACMA’s collection.

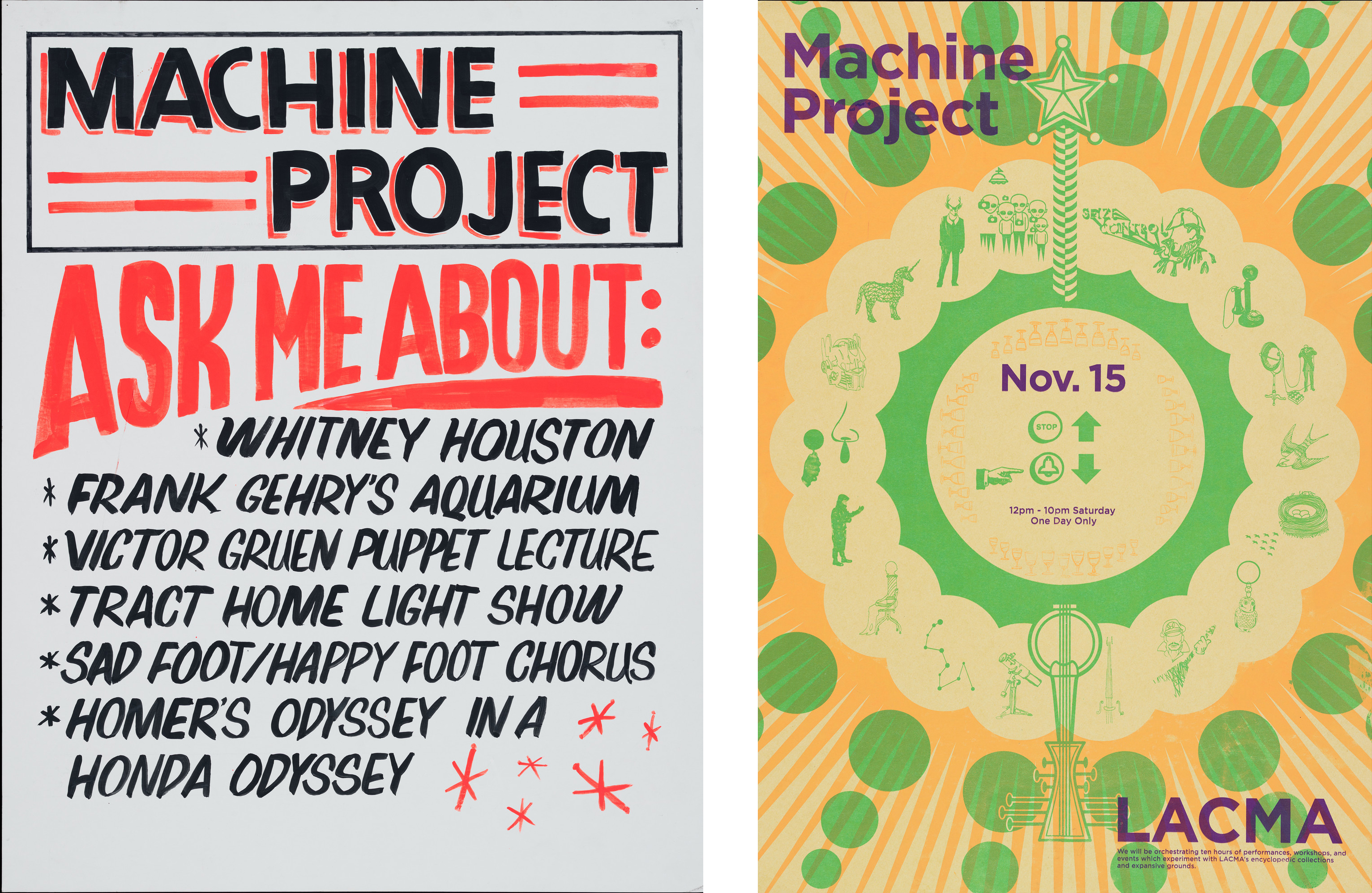

This archive of 247 posters from the Los Angeles art collective Machine Project (2003–2018) documents the wildly inventive workshops, screenings, performances, residencies, and other events that the group organized throughout its 15 years of existence. At the same time, the collection presents a window into L.A. graphic design of the early 21st century, including works by both established and emerging designers. Machine founder Mark Allen provided few guidelines and scant event details to the designers, allowing them ample space for creative experimentation.

Internationally acclaimed California weaver James Bassler adapts textile traditions from around the world, exploring issues of global exchange, politics, and other aspects of contemporary life. In the 1970s, Bassler lived and worked in Oaxaca, where he became deeply engaged with the region’s celebrated indigenous textiles. Huipil takes its name and form from the ubiquitous Mesoamerican tunic. This important early work exemplifies the artist’s cross-cultural melding, incorporating native silks from Oaxaca as well as natural dyes from both Mexico and California.

Los Angeles artist Gerardo Monterrubio describes Puño de Tierra as “a meditation on certain belief systems and rituals related to death.” The muscular porcelain form is sheathed with a muralistic collage of images drawn with underglaze pencil. In this work, Monterrubio layers scenes from his childhood in Oaxaca with funereal iconography from indigenous American cultures, as well as other sources.

In 2005, American-trained architect Bijoy Jain established his award winning practice Studio Mumbai in his hometown. Collaborating with local artisans skilled in traditional materials, the firm has built a reputation for site-specificity and sustainability. The back of the chair of Brick Study III bench is made of many miniature bricks formed from the mud and water at Studio Mumbai. Produced for the Brussels gallery Maniera specializing in artist and architect designed pieces for the home, the bench is part of Studio Mumbai’s first range of furniture.

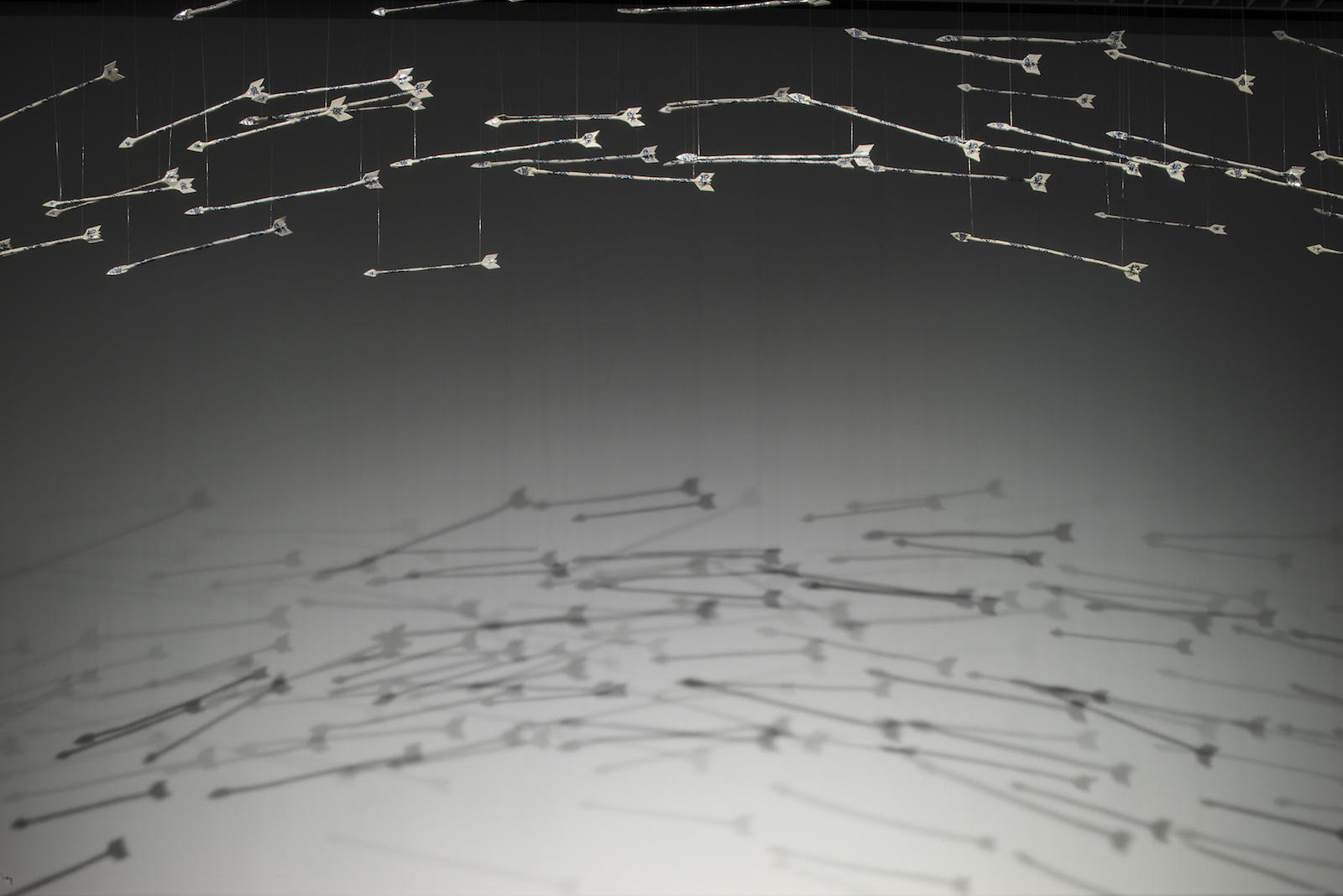

Nicholas Galanin is an Alaskan artist of Tlingit/Unangax̑ and non-Native descent. He calls attention to the restrictions and discrimination that Indigenous people in America still dream of overcoming in his poetic installation I Dreamt I Could Fly. Made from delicate porcelain (a material first imported from Europe and Asia), Galanin’s traditional arrows no longer afford food or protection. Though suspended in mid-flight, they will surely shatter upon impact. This work is on view through September 3, 2018, at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona where it features in his mid-career retrospective Dear Listener: Works by Nicholas Galanin curated by Erin Joyce.