We have recently reinstalled the Korean Art gallery! We invite you to a feast of traditional works from the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), presenting embroideries on badges and seven paintings embracing diverse genres and formats. These embroideries and paintings show the artists’ rich imaginations and symbolic gestures of the time.

In the corridor before the gallery, the embroidered badges, or Hyungbae, greet the viewers. These embroidered badges were patched onto government officials’ uniforms to convey their status and rank. Their titles were identified by the specific animals on the badges such as cranes, tigers, and leopards. Among the badges, an imaginary animal is depicted on Badge (Hyungbae) of Imperial Rank with Mythical Animal (Girin). Girin is one of the four divine animals along with the dragon, the turtle, and the phoenix. It has the head of dragon, the body of a deer covered with scales, the thick tail of cow, the flat hooves of horse, and horns covered with flesh. This mythical creature neither tread on the grass nor harmed any other animals. Because of its benevolence, there is a myth that the girin only appears in the presence of sages. It is said that that the girin appeared when Confucius was born. This myth led people to believe girin as a symbolic creature which brings a benevolent sage like Confucius as well as good fortune to the world. In Korea, girins appear in murals from the Goguryeo Kingdom (37 BCE–668 CE) and on roof tiles from the Unified Silla Kingdom (676–935). The girin on a hyungbae denotes an imperial rank of the prince. The badge on display is similar to the hyungbae of Yi Haeung (1820–1898), in the collection of the National Museum of Korea. Yi Haeung, known as Heungseon Daewongun, was regent to King Gojong (r. 1863–1907), the last king of Joseon and the first emperor of Korea.

Compared to the delicately embroidered mythical creatures like the girin, Korean folk painting, or minhwa, represent creatures in a comical way, as seen in Tiger under Bamboo and Pine Trees in the main gallery space. In Korea, tigers often appear in traditional fairy tales, legends, and the myth of Dangun, the legendary founder of Korea. These stories often start with the phrase “once upon a time when tigers used to smoke,” which shows a close affinity to tigers. In folk painting, the tigers are depicted as friendly, fearful, brave, and even divine. On the other hand, tigers in folk paintings are personified as corrupt officials of the government. Here, the tiger in this folk painting is remarkably rendered with humor and satire shown through its face and pose. Despite its glaring eyes and devious smile, the tiger is still portrayed as a friendly animal rather than a frightening or a sacred one.

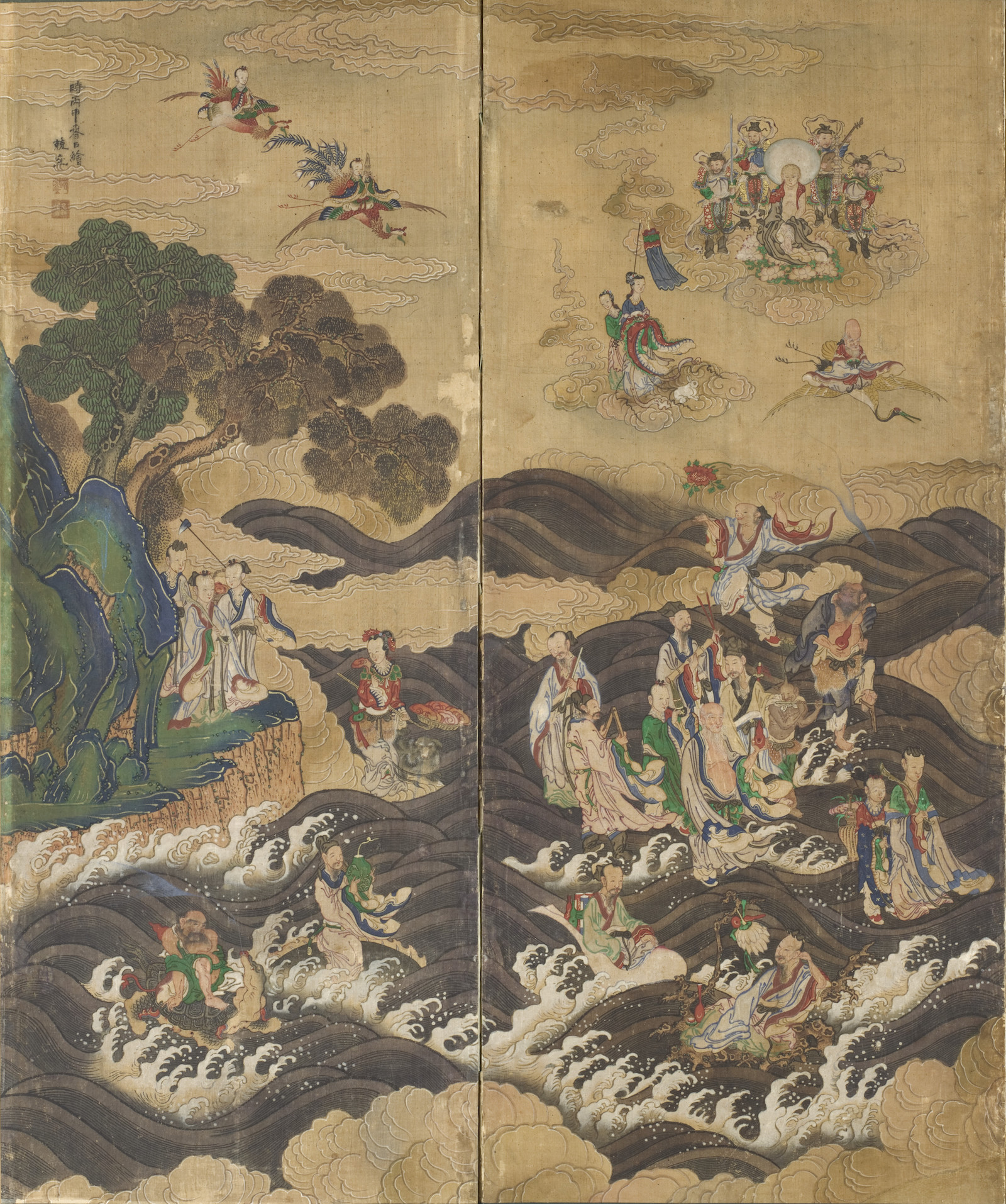

There are also two folding screens depicting imaginary gatherings from Chinese legends. These two meetings were popular subjects in the late Joseon dynasty. In The Banquet of Seowangmo (Ch. Xiwangmu), Queen Mother of the West, the imaginary figure, Seowangmo, is holding a grand banquet that happened every three thousand years when the peach trees blossomed.

.jpg)

Seowangmo is enthroned the middle of the painting, amid ripened peaches. Music and dance are performed by Daoist fairies and phoenixes in front of the queen.

On the left side of the painting, immortals invited to the banquet are descending from the sky and riding the waves to cross the sea.

The painting also depicts Buddhist figures at the top of the second panel from the left; a Buddha with the four heavenly guardians of Buddhism is descending from the sky. It has been suggested that this figure is a character, Seongjin, from a classic Korean novel, A Dream of Nine Clouds by Kim Manjung (1637-1692). The novel tells of Seongjin being reborn as Yang Soyu, relishing his life replete with wealth and honors. Yang Soyu, however, realizes that life is as fleeting as an illusion, and in the end finds that he merely dreamed being Yang Soyu. This novel depicts a fantastical view of the protagonist’s dream journey, but also conveys the profound lesson that life is no more than a mere dream.

There is no doubt that Korean paintings in the Joseon dynasty were greatly influenced by Chinese art of the time. Nonetheless, artists in Korea interpreted the tradition with their own aesthetic perspectives and elaborated on previous iterations of the painting. Explore these classical Korean paintings as well as Elegant Gathering in the Western Garden, Squirrel and Grape by Yi Chun (active c. 1600–1700), Bamboo, and The Sixth of the Nine Bends, Wu Yi Mountain (Ch. Xing Zhong Feng) in the Korean Art gallery, in the Hammer Building, Level 2.