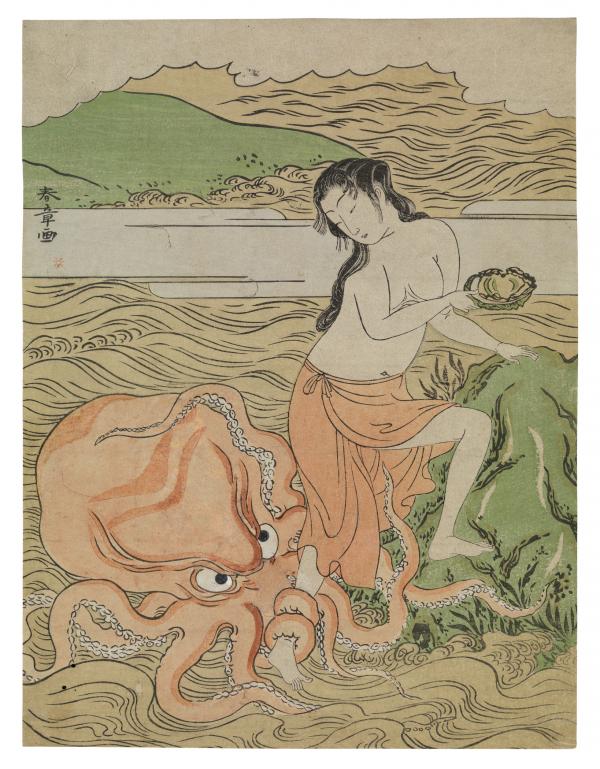

This Japanese woodblock print, Abalone Fishergirl with an Octopus (c. 1773–74) by Katsukawa Shunshō, was selected for inclusion in an upcoming touring exhibition titled Every Living Thing: Animals in Japanese Art. The exhibition is co-organized by the National Gallery of Art, the Japan Foundation, and LACMA, and co-curated by Robert Singer, curator and department head of Japanese Art at LACMA, and Masatomo Kawai, director of Chiba City Museum of Art. It will feature works of art in a broad variety of media, dating from the 6th century to the present day.

Prior to any exhibition or loan, conservators at LACMA assess an object’s condition and determine whether or not it will require treatment before going on view. In most cases, these kinds of treatments are minor stabilization efforts, such as mending small tears or consolidating flaking paint, the kinds of interventions that do not noticeably alter the appearance of an object. In contrast, Abalone Fishergirl presented an aesthetic problem that required careful consideration and a more involved treatment.

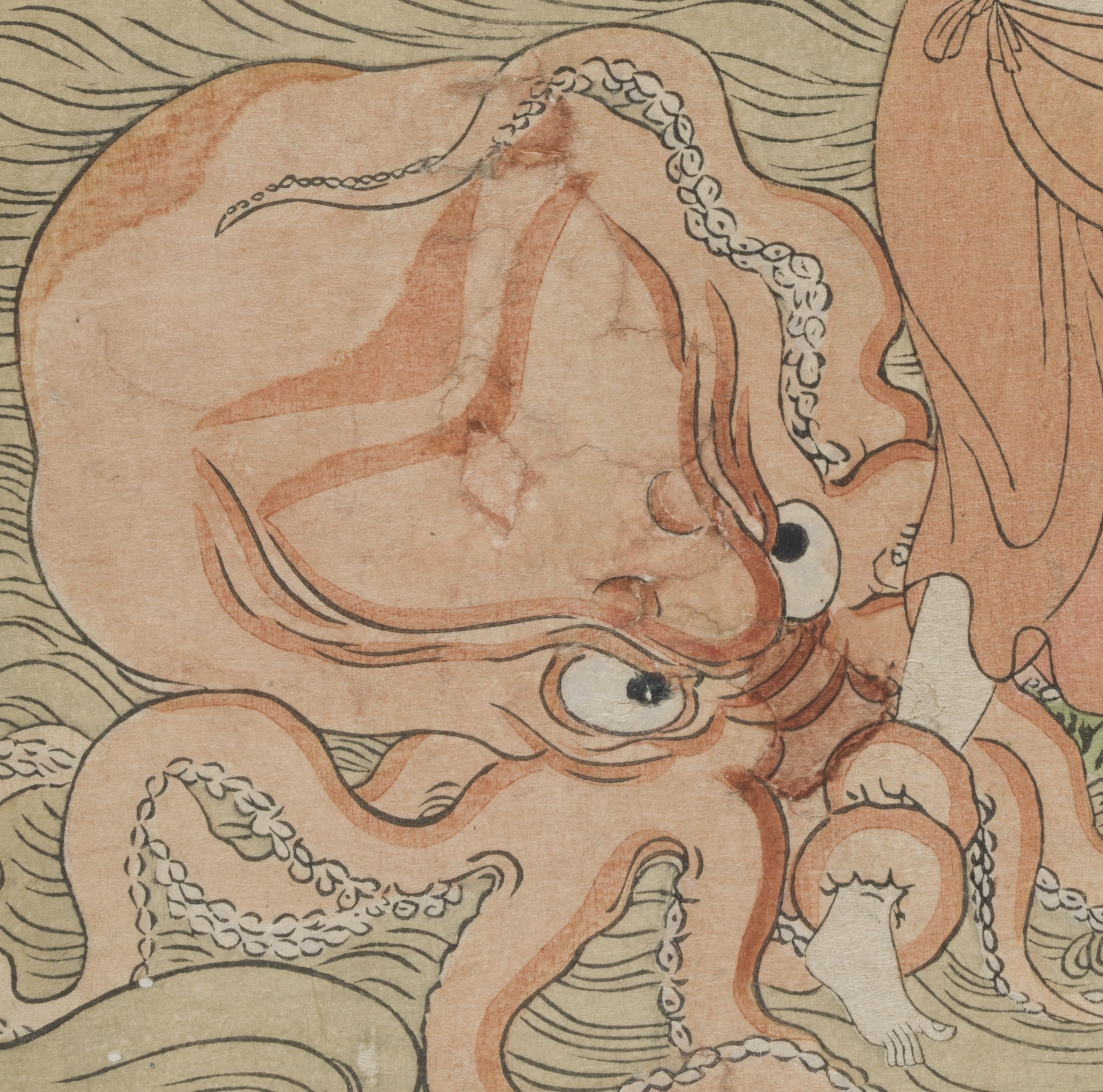

At some point in its past, the print had suffered damage in the form of tears and losses in the area of the octopus’s head. This damage was later repaired by lining the print overall with a second sheet of paper, and painting in the lost areas of the image. It was in this state that the print was acquired by LACMA in 2003. The print was structurally sound and the media stable, but the retouched area was problematic. It drew attention away from the rest of the image, and didn’t appear to correspond to the original design of the print. The paint was too dark, and in some cases, completely new design elements had been painted over the original. The overall effect was confused and visually disturbing. The octopus appeared battered and bruised, and its expression was simultaneously maniacal and inscrutable. I discussed the print with curators and my conservation colleagues, and there was a general consensus that the old repairs were distracting enough to warrant their removal.

Prior to beginning treatment, we deliberated about how I would fill in the missing image areas. The best option, we agreed, would be to find another, intact impression of the print that would clarify what the original design had been. This proved to be more difficult than anticipated. My colleagues and I scoured auction catalogs and online museum catalogues, and reached out to curators and art historians both in the United States and Japan. In the end, we came up empty-handed. The print seems to be quite rare, and every image available is of LACMA’s impression.

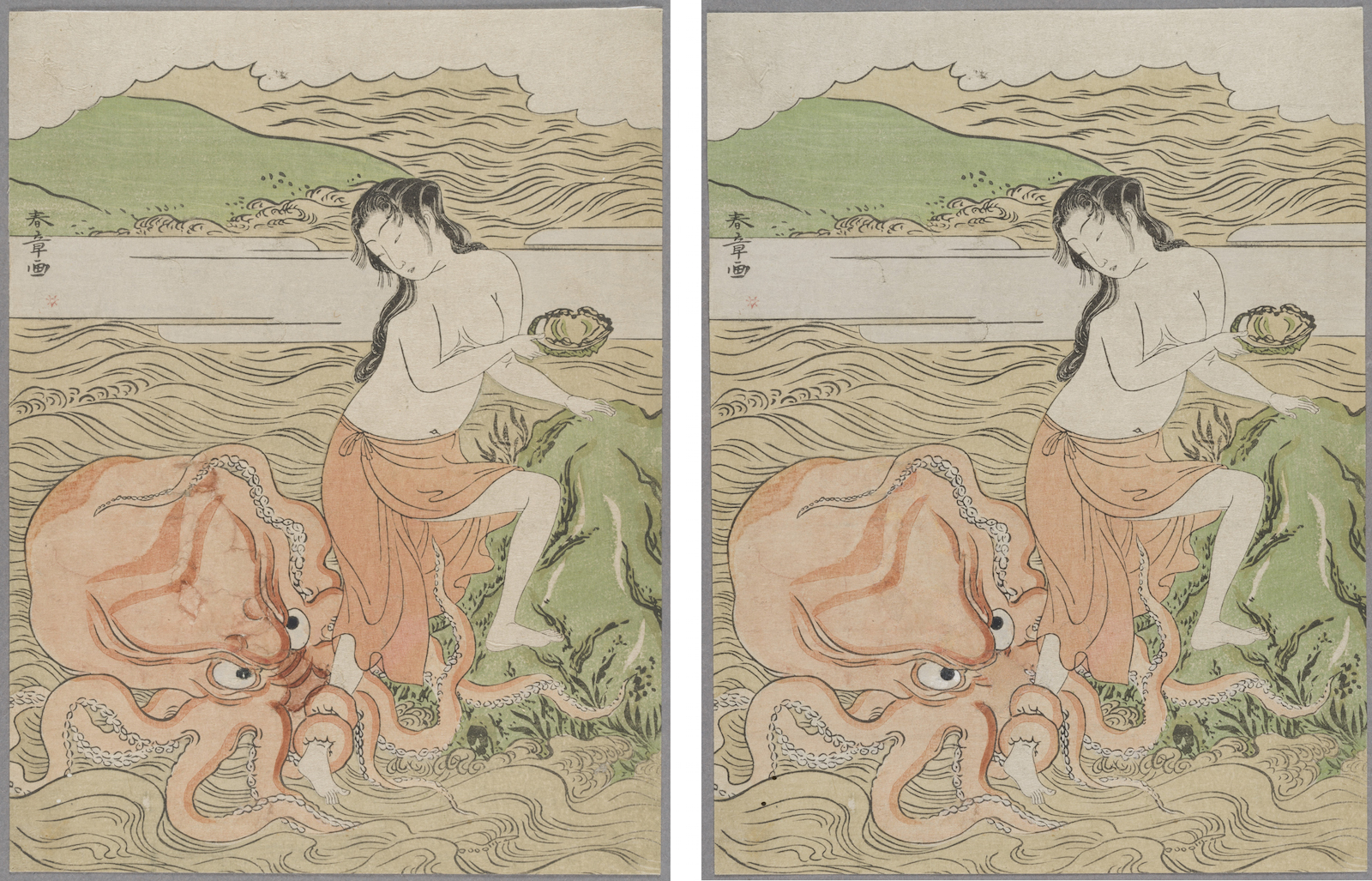

Somewhat deflated, I returned to the drawing board. I considered recreating the design of the existing fills, but the more I examined the print under the microscope, the clearer it became that the painted areas were a fabrication that had no relationship to the original printed image. Instead, with the approval of the curator, I decided on an approach that would reduce the visual impact of the damaged area while leaving the missing features intentionally vague.

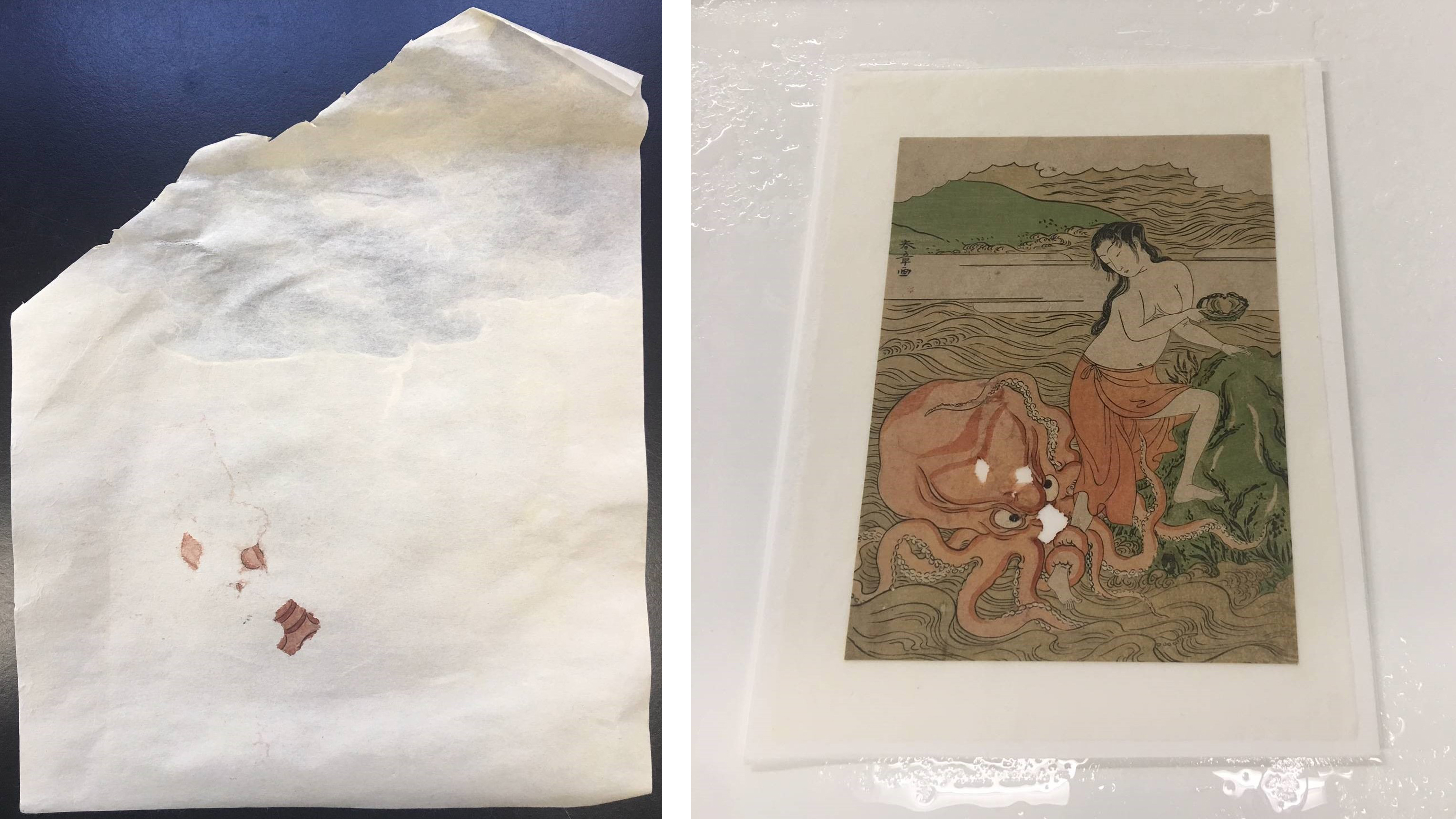

The treatment was performed in several steps. I did some selective surface cleaning and tested the inks for solubility in water. I then humidified the print overall, and wetted it up to soften the lining adhesive. Next, I peeled the lining paper away, and washed the print on a wet blotter to draw out minor discoloration and reduce residual adhesive from the lining.

After the print was dry, I used a scalpel and a microscope to carefully reduce areas of overpaint. Losses in the paper were subsequently filled with pieces of Japanese paper adhered with wheat starch paste, which is easily reversible with water. Very small Japanese paper overlays were also adhered over the most disturbing tear lines to reduce their appearance. Finally, the fills and overlays were in-painted with watercolors, using a very fine brush.

As planned, this treatment reduced the visual impact of the damaged area of the print enough for it to be exhibited, while still allowing it to be “read” as incomplete. For now, this is the most satisfying result that could be achieved. It is my hope that in the future, another impression of this print will surface, and we can learn what Shunshō originally intended for his octopus. At that point, the missing information can be added, or if necessary, the Japanese paper fills I created can be removed with a little water and replaced altogether. Art conservation is always a work in progress.

If you have information about another copy of this print, please contact LACMA’s paper conservation lab! Every Living Thing: Animals in Japanese Art will be on view at LACMA in September 2019.