The precursors of many contemporary African-American quilts can be traced back to evidence of quilted textiles in ancient Egypt, and the domestication of cotton in Mali along the Niger River more than 2,000 years ago. More directly, from the mid-17th to mid-19th century, ancestors of African Americans and the aesthetics connecting African and African-American artistic traditions were brought to the Western Hemisphere from West and Central Africa.

The five extraordinary African-American quilts in this collection, dating from the early 1940s to 1992, share salient design qualities such as bright contrasting colors, asymmetry, changes in scale, flexible irregular patterning, and surprising juxtapositions, which often distinguish Afro-traditional quilts from conventional Euro-traditional quilts. Each of the five African American artists represented—Mary Lue (“Mother”) Brown, Effie Jackson, Laverne Brackens, Sherry Byrd, and Rosie Lee Tompkins—chose fabric (often factory scraps or recycled fabric and clothing) that they cut and pieced (usually without measuring) and stitched into original creations, frequently working without a predetermined design in mind. Structural features included the use of pieced strips of fabric, similar to the strip-woven textiles stitched into kente prestige cloths for the Ashanti and Ewe elite; bordering systems that favored non-four-sided arrangements found on many African ceremonial textiles; and improvisational designs that unwittingly made cultural aesthetic connections with West and Central African rhythms of music, dance, and art.

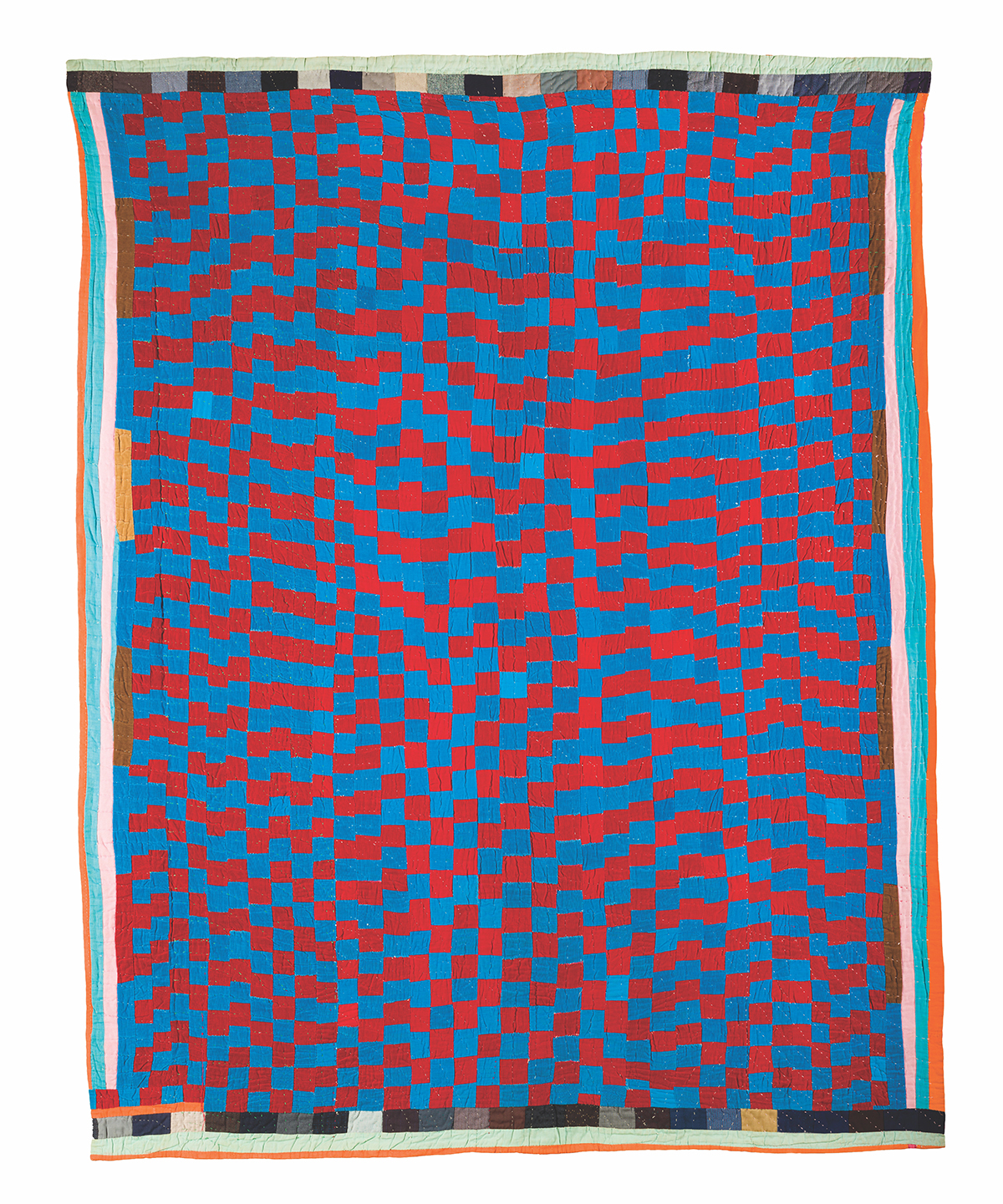

The unbalanced checkerboard pattern of Mother Brown’s Hit and Miss is composed of irregularly sized squares of red-and-blue cotton corduroy stitched into long strips then joined to form the quilt. Squares hit or miss the grid resulting in a pulsating composition.

Effie Jackson stitched rectangular fabric strips together to create a variation of the conventional “double-strip” American quilt pattern, but incorporated a pair of side borders utilizing elongated pattern blocks that relate to African bordering styles.

Laverne Brackens intentionally offset irregularly sized fabric pieces in making Strip, an asymmetrical composition of unevenly sized dark-and-light printed knit fabric. Brackens embraced the misalignments of the strips believing that it challenged her creativity and made the quilt unique. Her daughter, Sherry Byrd, created Roman Stripe Variations without attention to exact measurements because “It just takes the heart out of things.” She improvised the size and number of red, black, and red-and-white modular patches, choosing not to stitch the pattern blocks into straight parallel strips. Together with a central (but off-centered) medallion, blue patchwork lines, and playful manipulation of red-and-white striped knit patches turned in different directions, Byrd produced a dynamic asymmetrical design akin to ceremonial raffia skirts patched with abstract asymmetrical designs by Kuba women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Rosie Lee Tompkins's 1983 Hit and Miss Strip is an impressive amalgam of fragments of velvet and velveteen clothing. As her hands assembled small pieces of cloth, her mind managed the variations of color, shapes, and scale that provided further opportunities for improvisation.

The artistic achievements of these five African American women have been celebrated in exhibitions and publications throughout the United States. Their exuberant improvisational designs suggest their shared cultural heritage and give expression to their individual artistic talents.

During our 33rd Collectors Committee Weekend (April 12–13), members of LACMA's Collectors Committee generously helped the museum acquire eight works of art spanning a breadth of eras and cultures.