In May, our Tuesday Matinees series will continue its journey taking a look back 50 years ago at the state of American cinema, specifically the years from 1969 to 1972. The coming month’s focus will spotlight one of the oldest and certainly the most iconically American of all film genres: the Western. It was during this era that the Western evolved into one of the more interesting and creatively daring genres ever seen in American cinema. By leaning into and wrestling with the mythology of the American Western, the genre became a reflection of the times and began to question its own character.

What originally set the Western apart from other genres was how entwined it was with the advent of cinema as we know it in 1895. The 1890s saw the twilight of Westward Expansion, the depravity of the Wounded Knee Massacre, and the last of the exoticised Buffalo Bill’s Wild West tours. As America was transitioning into a new century, it channeled its nostalgia for this near past into film, just as the medium itself was also transforming from a technical curiosity to a new artform that would become its own industry. Over the next 60 years, Westerns would evolve and remain a staple of nearly every studio, creating and sustaining a uniquely American iconography. The Western’s roots grew from a romanticized history of mythic proportions to a platform for all-American rugged individualism. That all changed with the rise of the counterculture in the late 60s. The genre became less about once set-in-stone ideals and took a shift toward open-ended questioning and doubt.

This partly stemmed from the decades of near non-stop wars and the expansion of American influence since the 1890s, and also as a result of how differences in opinion across the generational divide affected the changing interpretations of American values. New audiences no longer believed or wanted classical Westerns that presented an idea of America within a morally black-and-white world. In the era of Vietnam and Nixon, the genre took on a new existential grittiness and confusion that mirrored the cultural rot of the time. The assured swagger of old mainstays like John Wayne was passé and a new ethos of earnest questioning by rising stars such as Robert Redford would begin to shift the genre. This was a genre questioning its own DNA, digging deep into quandaries of what it means to be free, and confronting the national shame of the Native American Genocide and the toll of America’s legacy of violence. This was the Western’s last great era and it was finally facing itself.

May 7 | True Grit

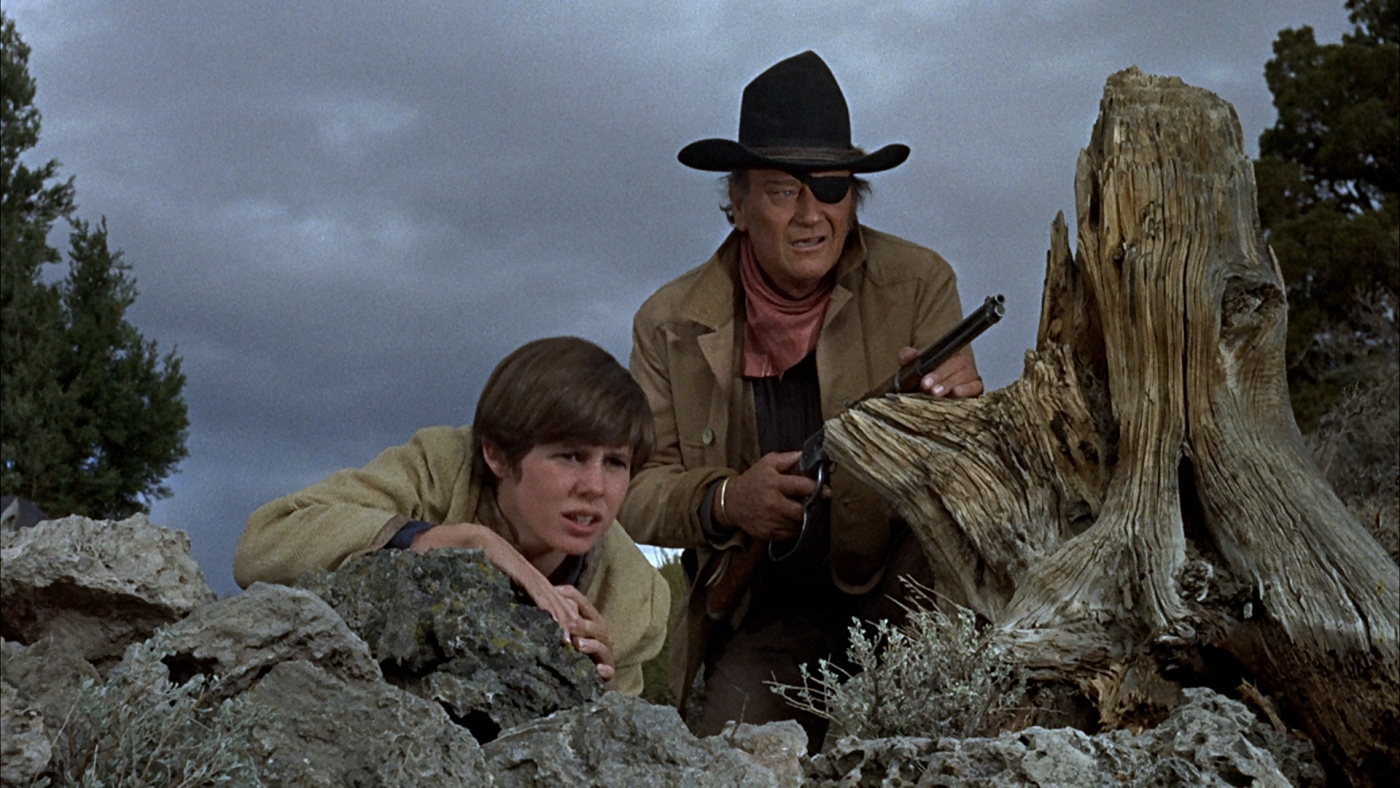

1969, 128 minutes, DCP | Directed by Henry Hathaway; produced by Hal B. Wallis; written by Margeurite Roberts; with John Wayne, Kim Darby, Glen Campbell, Robert Duvall, Jeff Corey, Dennis Hopper, Strother Martin, and John Fiedler

After hired-hand Tom Chaney (Jeff Corey) murders the father of 14-year-old Mattie Ross (Kim Darby), she seeks vengeance and hires U.S. Marshal "Rooster" Cogburn (John Wayne), a man of "true grit," to track Chaney into Indian territory. As the two begin their pursuit, a Texas Ranger, La Boeuf (Glen Campbell), joins the manhunt in hopes of capturing Chaney for the murder of a Texas senator and collecting a substantial reward. The three clash on their quest of bringing the same man to justice.

May 14 | Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

1969, 110 minutes, 35mm | Directed by George Roy Hill; produced by John Foreman; written by William Goldman; with Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katharine Ross, Strother Martin, Jeff Corey, and Henry Jones

The true story of fast-draws and wild rides, battles with posses, train and bank robberies, a torrid love affair, and a new lease on outlaw life in far-away Bolivia. It is also a character study of a remarkable friendship between Butch—possibly the most likeable outlaw in frontier history—and his closest associate, the fabled, ever-dangerous Sundance Kid.

May 21 | Ulzana’s Raid

1972, 103 minutes, 35mm | Directed by Robert Aldrich; produced by Carter De Haven Jr.; written by Alan Sharp; with Burt Lancaster, Bruce Davison, Richard Jaeckel, Jorge Luke, and Joaquín Martínez

When word arrives that Apache warrior Ulzana has assembled a war party and left the reservation, the United States Army pegs veteran tracker McIntosh (Burt Lancaster) and Apache Ke-Ni-Tay (Jorge Luke) to lead a young, prejudiced lieutenant's (Bruce Davison) troops to find Ulzana. Outmaneuvered and unfamiliar with the terrain, the cavalry struggles to stop the long-mistreated and raging Apaches from destroying everything in their path in what initially seem like senseless acts of violence.

May 28 | The Last Movie

1971, 108 minutes, DCP | Directed by Dennis Hopper; produced by Paul Lewis; written by Stewart Stern; with Dennis Hopper, Stella Garcia, Don Gordon, Julie Adams, Sylvia Miles, Peter Fonda, Henry Jaglom, Michelle Phillips, Kris Kristofferson, Dean Stockwell, Russ Tamblyn, and Tomas Milian

Consciously self-reflexive and co-written by Hopper and Rebel Without A Cause screenwriter Stewart Stern, The Last Movie follows a Hollywood movie crew in the midst of making a western in a remote Peruvian village. When production wraps, Dennis Hopper, as the baleful stuntman Kansas, remains, attempting to find redemption in the isolation of Peru and the arms of a former prostitute. Meanwhile, the local Indians have taken over the abandoned set and begun to stage a ritualistic re-enactment of the production—with Kansas as their sacrificial lamb.

Join us each Tuesday at 1 pm for these classic screenings. Our June listings will explore crime films from this era.