The legacy of Charles White spans multiple decades and three cities: Chicago, his birthplace; New York, where he grew in prominence as an artist and joined social causes; and Los Angeles, where his art and activism coalesced during the civil rights movement.

LACMA celebrates White’s legacy in a pair of exhibitions currently on view. Charles White: A Retrospective provides a long-overdue examination of White’s career and impact on the cities where he lived and worked. A companion exhibition, Life Model: Charles White and His Students, explores his role as an empowering teacher and mentor through the work of the students who revered him. The latter is presented at LACMA’s satellite gallery at Charles White Elementary School, which occupies the former Otis Art Institute campus in MacArthur Park, where White was a faculty member.

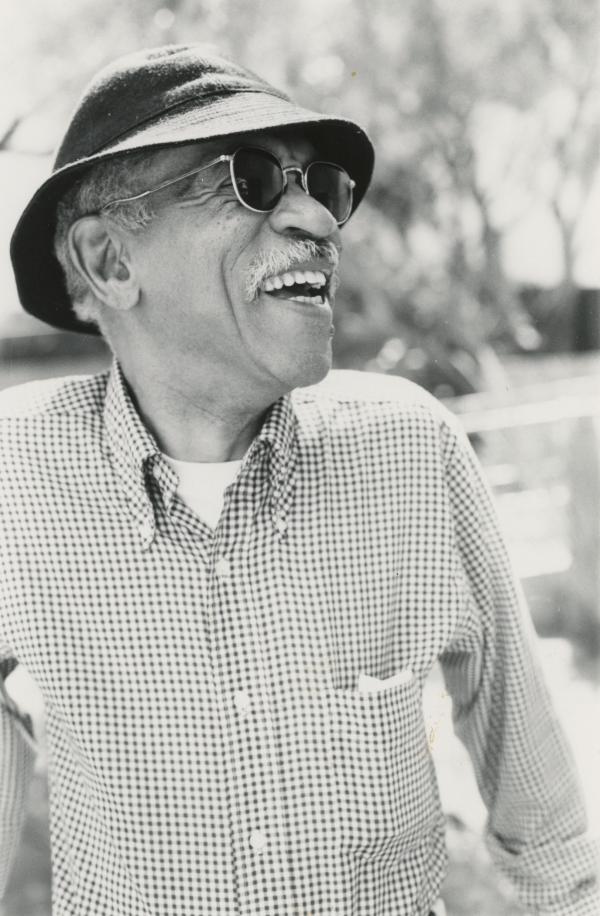

White and his wife Francis moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1956. At the time White was already an established artist in New York, but Los Angeles is where he became a leading figure in the African-American arts community, as well as a significant cultural voice who helped transform the city into a notable place for art making.

L.A. is also where White produced some of his most well-known and strident political artworks that speak to his evolution as a cultural activist. Since the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s, the Whites had supported the nonviolent resistance of Martin Luther King Jr., which aligned with the artist’s humanistic ideals and the dignity he bestowed on the African Americans who populate his drawings, paintings, and prints. This positive, optimistic perspective resulted in works like the drawing Birmingham Totem (1964), a response to the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four young girls. In a talk given at LACMA in 1969, White said of the drawing: “Instead of trying to re-create an event, I put a reaction on paper...I drew a picture of a crouched male figure holding a plumb line over the rubble. The symbol and the statement were intended to suggest that perhaps destiny has chosen blacks to be the catalyst for change in our society. The crouched figure was symbolic of the architect who would help to do the planning in creating a new society.”

White quickly made inroads in the L.A. art scene, which in the late 1950s was still smaller and distinct from those in other major cities. His art remained figurative and resolutely focused on people, while the East Coast avant-garde gravitated toward Abstract Expressionism and, later, Pop Art and Minimalism. As the civil rights movement progressed, White’s art began to reflect his growing impatience with the pace of social change—namely in J’Accuse (1966), a group of 12 charcoal and ink-wash drawings, and the Wanted Poster Series, begun in 1969.

The title J’Accuse is a reference to the 1898 letter by Émile Zola to the French president exposing the political injustice of the Dreyfus Affair (when Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, was falsely accused and imprisoned for spying). All 12 of the drawings were on view at the Heritage Gallery for a 1966 show when, just before the opening, White changed the titles of every piece to J’Accuse. His repeated use of this title “echoed the federal government’s recurring inability to recognize black humanity,” according to Ilene S. Fort, curator emeritus of American Art, who organized the LACMA presentation of the retrospective.

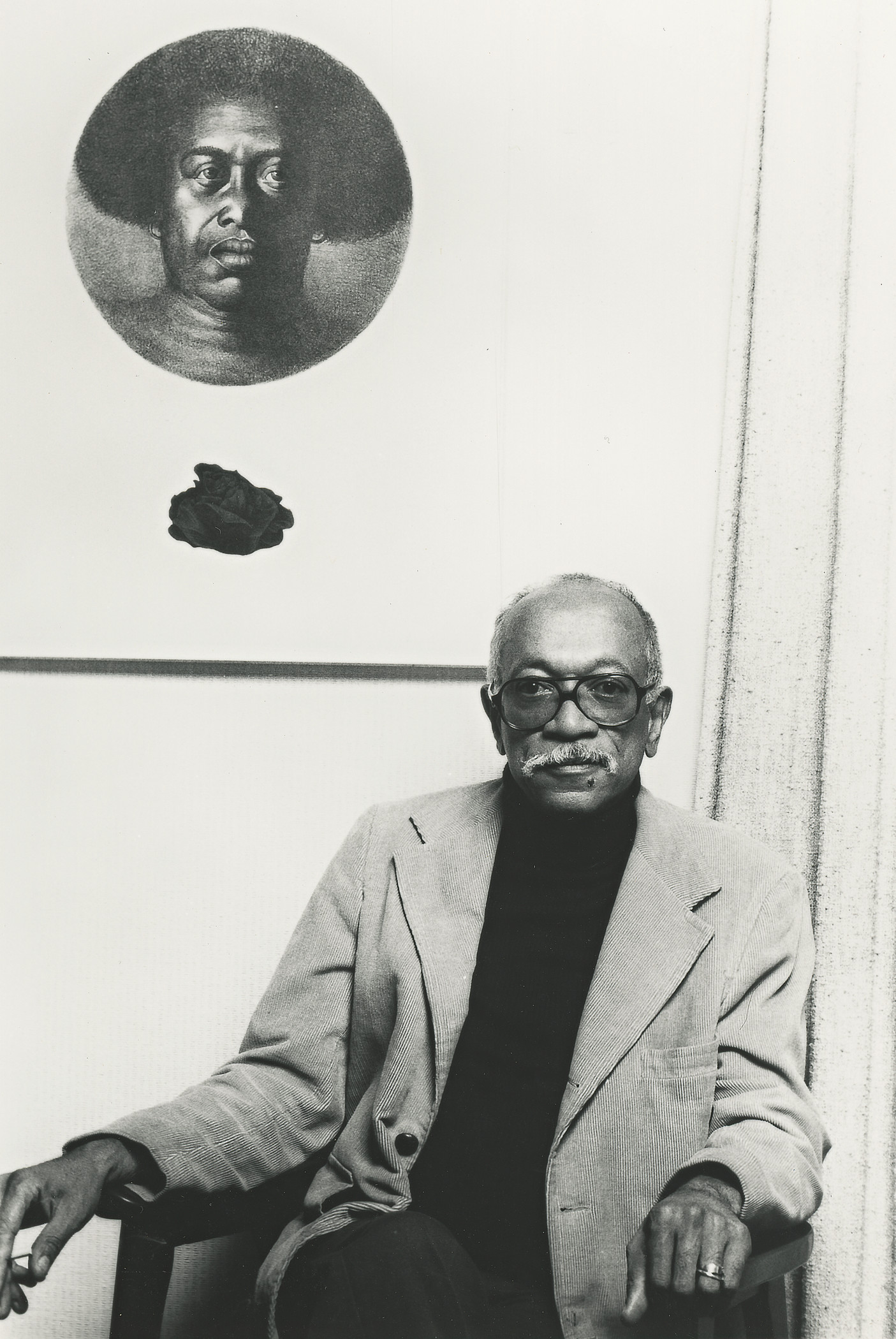

The Wanted Poster Series, drew both its subject matter and visual treatment from a collection of 19th-century newspaper advertisements for auctions of enslaved people and wanted posters for those who escaped. As White explained in his 1969 talk at LACMA, “We are all fugitives.” The faces and figures in the series are set against or framed by backgrounds of fractured planes that produce the effect of crumpled or creased paper—an effect that White transferred to many of his later works. The figures are accompanied by faint texts, numbers, and images like pointing hands that recall the historical source material. By appropriating that vocabulary and deploying it in a contemporary context, White asserted that the country’s history of slavery still reverberates through the lived experience of African Americans in the present day.

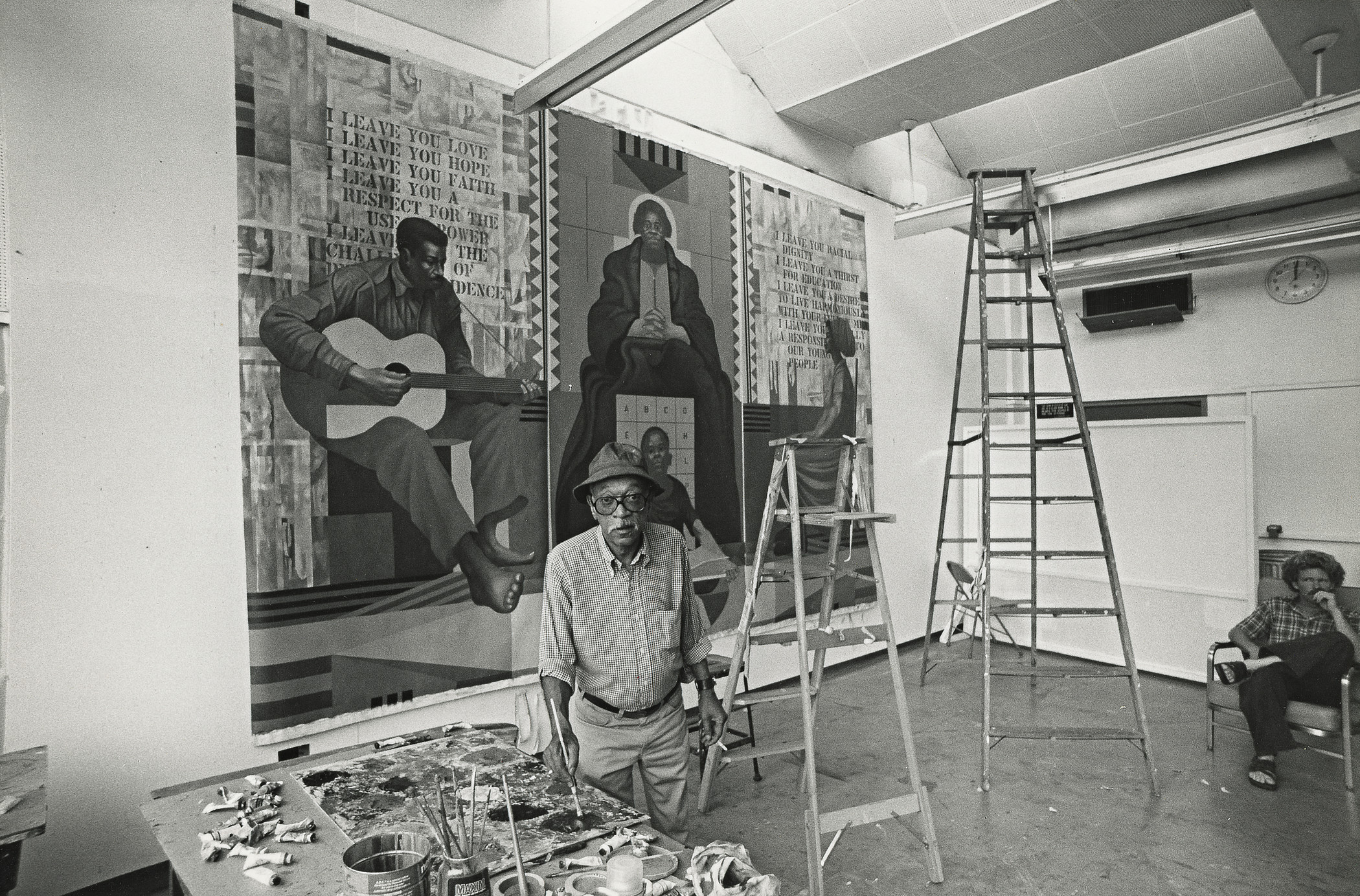

In 1965, White began teaching at Otis Art Institute as the first African-American member of the school’s faculty. Teaching and encouraging young artists was as integral a part of White’s career as his own practice. As he wrote in 1943, “I feel that in advancing my ideas in the art field, I will have to spend much of my time teaching and encouraging young Negro art students. We have the opportunity to make a great contribution to American culture, but it will have to be a group effort rather than an individual contribution.”

Life Model: Charles White and His Students at Charles White Elementary features work by many of White’s students, including David Hammons, Judithe Hernández, Kerry James Marshall, and Kent Twitchell, alongside sketchbooks, photos, and archival footage that illuminate White’s pedagogy. In White, these students found a role model carving out a place in a racist art establishment, as well as strong encouragement for making socially engaged art. In addition to teaching technical skill, he urged them to become “thinking artists” guided by their own individual perspectives.

“He had a profound influence on a generation of artists who have gone on to produce some of the most incisive social commentary in contemporary art, and I think the amazing variety of art in this exhibition says a lot about his respect and care for each of their unique voices,” says C. Ian White, the artist’s son, who co-curated the Life Model exhibition. “It’s incredibly meaningful to present this show in the very place where he taught.”

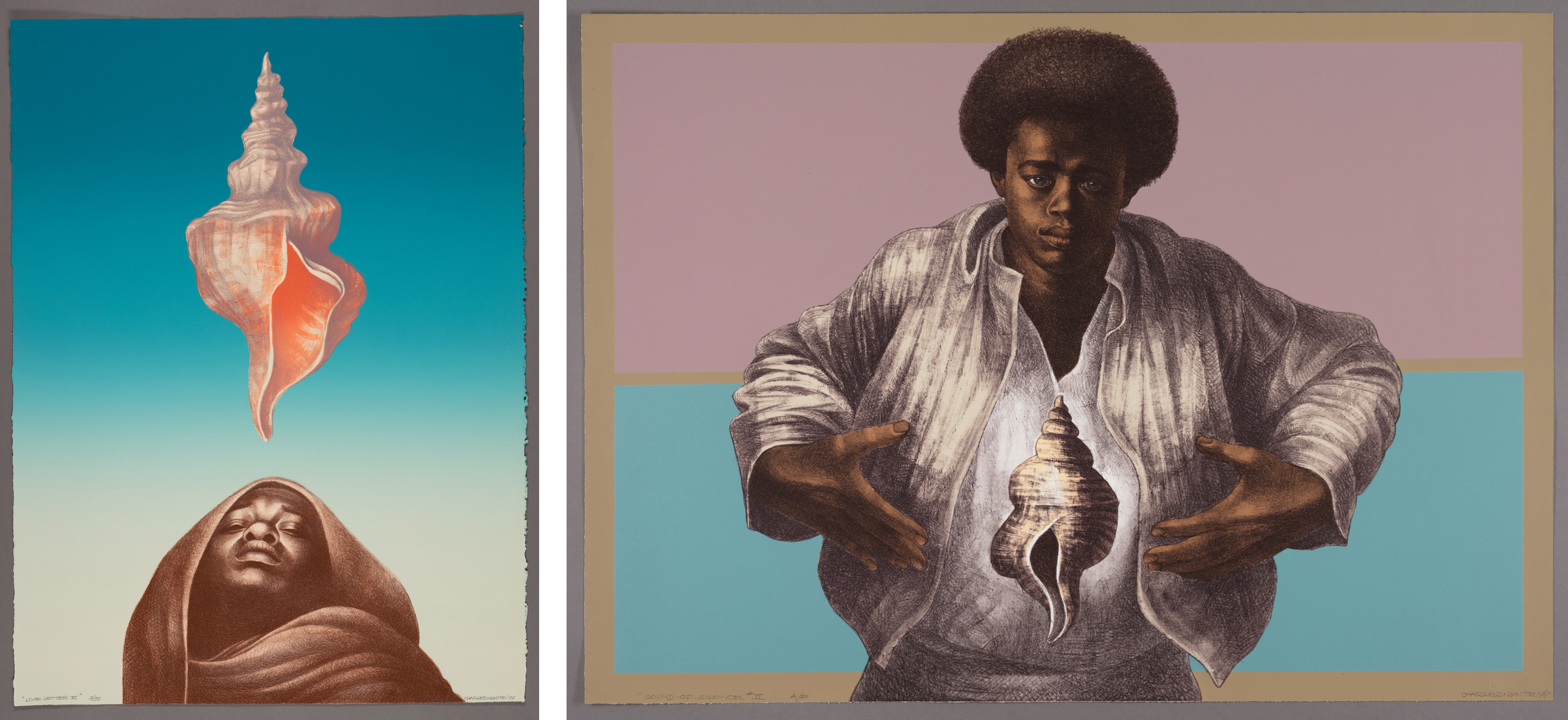

White’s work was exhibited at LACMA for the first time in 1971, when the museum organized Three Graphic Artists at the urging of the Black Arts Council, formed in the late 1960s by LACMA staff and local artists. Alongside works by Timothy Washington and his former student David Hammons, the show featured examples from White’s J’Accuse and the Wanted Poster Series, as well as the large ink drawing Seed of Love, which LACMA acquired for the permanent collection.

By then White was a nationally recognized figure in the black arts movement, known not just for his art but also as an activist and important public speaker. While some criticized the grouping of work by such a senior figure with that of two lesser-known local artists, White had no objection, showing his deep commitment to nurturing other African-American artists and increasing the visibility of black art.

White would later serve on the advisory board of L.A.’s California Museum of Afro-American History and Culture (now the California African American Museum), and was involved in the planning of LACMA’s landmark 1976 traveling exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art. In addition to eight of his works in the show, White created a lithograph for the museum, I Have a Dream, which was selected by the organizers as the exhibition poster. He insisted that the edition of 125 be sold for just one dollar and distributed free in L.A. public schools.

I Have a Dream appears in Charles White: A Retrospective, more than 40 years after it was commissioned. The image of a mother cloaked in a flowing sheet, ceaselessly cradling her child, encompasses the essential themes that make White’s oeuvre timeless and relevant: the weight of American history, the endurance of the oppressed, and, in her face upturned toward the light, hope for the future.

Charles White: A Retrospective is on view through June 9 in LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion. Life Model: Charles White and His Students is on view through September 15 at Charles White Elementary School in MacArthur Park. This article was first published in LACMA’s Spring 2019 Insider publication. It has been condensed slightly for Unframed.