LACMA recently received a gift of six works of Chinese contemporary art from donor Dick Ting-Chung Chen, by Fu Xiaotong, Taca Sui, Wu Jian’an, Guo Hongwei, and Yan Shanchun. They represent different generations, styles, and subject matter: from meditative black and white photographs to subtle, dream-like landscapes, these works engage with different aspects of Chinese history.

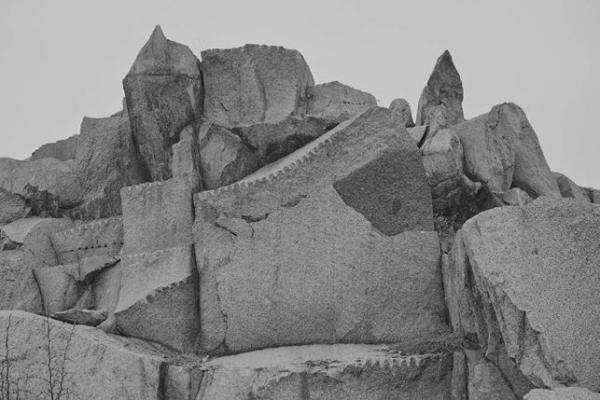

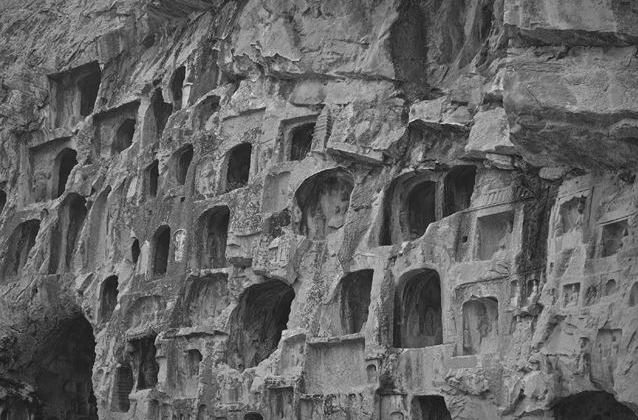

Taca Sui was born in Qingdao, China, in 1984, and has studied in both China and the United States. Both his Mount Jian (2015) and Longmen (2015) are part of a series of works titled Steles, in which the artist set out to document the places written about in the diaries of the late-Qing Dynasty imperial bureaucrat Huang Yi (1744–1802). Huang was a painter, poet, calligrapher, and amateur archaeologist, known for his study of stone steles. He recorded his studies in two diaries: Diary on Visiting Steles near Mount Song and the Luo River and Diary on Visiting Historical Steles from Jining to Tai’an. Taca Sui uses these diaries as written maps, searching for the places described by Huang and photographing them in the present day.

Fu Xiaotong (b. 1976) has developed an artistic practice that shapes paper into pieces that can be seen as both 3-D sculpture and 2-D wall-hanging artwork. The artist employs an awl to repeatedly pierce sheets of thick xuan paper—a traditional type of mulberry and hemp-based paper (often given the misnomer of “rice paper”) favored by historical and contemporary ink painters alike. By piercing the paper from multiple directions, Fu creates different textures, and raises and lowers her ground. She emphasizes her labor-intensive process by titling each work after the number of holes she creates. In this piece, she’s pierced her paper 518,580 times; although this is an immense number, it is typical of her work—Fu’s largest pieces feature millions of individually-poked holes.

Though he was born in 1980, one could posit that Wu Jian’an’s artistic practice is already nearly 40 years in the making. The artist’s work recalls experiences in his early childhood, which have shaped—literally and figuratively—his practice since he began committing himself to creating paper cuts in the early 2000s. Directly after the artist began making paper cuts, the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic broke out. Wu stayed safe by hiding out in his apartment, making figures to keep himself company. He recalls surrounding himself with cut figures as he sat on the floor of his apartment, feeling safe and protected.

Guo Hongwei’s (b. 1982) paintings have a near photo-realistic quality. He draws inspiration from varied sources, including childhood photographs, botanical illustrations, and objects from around his studio. Guo has a particular interest in stones, exposed to various geological materials in his youth, when his father held an administrative position at a mining company. The artist has also created works that capture shards of plastic from a painting plant near his studio, as well as inexpensive, man-made items. While some of his pieces appear similar to a wunderkammer or curio cabinet, others remind us of the wall of a natural history museum, arranging different specimens out in a grid, sometimes loosely sorted by size or color.

Although Yan Shanchun (b. 1957) lives in the same city as his main artistic subject, West Lake in Hangzhou, China, he chooses to paint his landscapes from memory. This puts Yan’s work in dialogue with the historical Chinese painting tradition of the imagined landscape—the creation of a landscape reflecting the personal interpretation of a place as opposed to a photorealistic rendition of nature. In a mode similar to European fresco painting, he starts with a layer of wet glue and plaster powder, creating a putty out of the two materials. After sanding down the surface, he paints with ink and cinnabar pigments, gamboge resin, or tea. Usually, he will repeat this process three or four times, adding new layers of putty, before sanding his ground and painting anew.

Although these works are not currently on view, LACMA is excited by these new additions to our swiftly growing collection of Chinese contemporary art. We look forward to exhibiting these works in the future, as part of an ongoing endeavor to bring contemporary Chinese art to Los Angeles.