The eighth annual meeting of the Decorative Arts and Design Acquisitions Committee (DA²)—which supports the acquisition of outstanding examples of decorative arts and design for the museum’s permanent collection—was held in May. This year’s meeting was a huge success, and through the group’s generosity, everything presented was acquired! We added objects in many of our strategic collecting areas, including modern and contemporary California design, Dutch design, and work that has direct dialogue with art already at the museum. And in accordance with LACMA’s collecting goal for this year, all objects acquired were designed by women! (In a few cases, artworks were executed in collaboration with men.)

The projects of Studio Drift in Amsterdam are among the most adventurous, thought-provoking, and aesthetically alluring in production today. Co-founders Lonneke Gordijn and Ralph Nauta have given new meaning to the term “cross disciplinary”—their work encompasses installation art, design, technology, sculpture, and film, and is made through collaborations with scientists, research facilities, programmers, and engineers. This process results in a profound exploration of peoples’ relationships to both nature and technology.

While their practice is moving more toward large-scale, site-specific installations, Fragile Future 3.13—a light sculpture consisting of three-dimensional bronze electrical circuits connected to actual dandelion seeds—is an outstanding example of their work. Nature’s survival strategies is a particular leitmotif for Gordijn. As she explained: “I wanted to understand what level of awareness on the environment an object could raise. Fragile Future uses the fragility of dandelion seeds as a strength.” The Fragile Future series started as Gordijn’s graduation project in 2005, and was the first project she and Nauta developed together after establishing their partnership. The series has continued to evolve ever since, in permutations including chandeliers and entire room installations.

For over 50 years, New York-based artist Michele Oka Doner has systematically studied the natural world and derived her formal vocabulary from it. She works in a multitude of media including bronze, terrazzo, silver, porcelain, wax, paper, and textiles to produce public art, sculpture, furnishings, costume, prints, drawings, and set designs. She has been the subject of many solo exhibitions—most recently at the Perez Art Museum in Miami (2016)—and books, such as the multi-authored Everything is Alive (Regan Arts, 2017) and Natural Seduction (Hudson Hills, 2003).

While all nature inspires her, the sea—its flora and fauna—is particularly resonant. A childhood spent in Miami Beach led to an intense affinity for myriad forms of marine life and subtropical vegetation. Coral Wave is not only among Oka Doner’s own favorite forms and only one of two chair designs executed in silver, it is also the first example of her work to be added to LACMA’s collection. This representation of the ocean’s bounty conveys Oka Doner’s mission to share both her wonder in our natural surroundings and the urgent need to cherish, protect, and incorporate the increasingly ephemeral world around us.

A stirrup cup is a small alcoholic farewell drink received once mounted on horseback or “in the stirrups,” which came to refer to the cup itself. In the form of a fox’s head, this type of stirrup cup was made specifically for riders departing on a foxhunt.

Developed for the emerging sport, this cup is a distinctively English Neoclassical design inspired by archaeological illustrations of ancient animal head cups from excavations in Southern Italy. It not only highlights the sources 18th-century designers took from antiquities, it also documents women’s participation in England’s industries. Although married women could not own property before 1870, widows could, and they gained recognition through the marking system established to guarantee the purity of silver. This fox’s head stirrup cup is hallmarked for Peter Bateman and Ann Bateman, a brother- and widowed sister-in-law continuing the business Peter’s mother Hester had made successful in her own widowhood.

Zizipho Poswa is co-owner of Imiso (meaning “tomorrow”) Ceramics, located in the regenerated Woodstock suburb of Cape Town. Building on the success of her business, she is now working with gallery Southern Guild in Cape Town’s Waterfront to create large-scale work.

Her Ukukhula series (meaning “growth”) consists of two highly abstracted and monumental sculptural forms. She relates them to her personal history and professional development as she expands her output from functional wares to collectible design. Attributing both masculine and feminine qualities to opposing aspects within each piece, she considers them to be a pair. These new works by Poswa, the first at LACMA by a South African craftswoman, expand the museum’s strong holdings of international contemporary studio ceramics.

Dora De Larios was, in many ways, a quintessential Los Angeles artist. Born in Boyle Heights to Mexican immigrant parents, De Larios was deeply influenced by the diverse city, infusing her work with the ceramic traditions from her Mexican heritage, as well as those of other cultures and modern artistic movements in L.A.

De Larios’s love for art began on a childhood visit to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, where she was deeply moved by the works of her ancestors. She pursued her passion at the University of Southern California, where she studied with important teachers including Susan Peterson and Viveka Heino. After graduation, she built a successful artistic career, creating both functional and sculptural works as well as significant public commissions. This Warrior, one of several such figures she created in the 1960s and 1970s, exemplifies her multicultural inspiration. It reflects both the expressive forms of ancient West Mexican figurines, and the round, hollow forms of Japanese Haniwa sculptures.

.jpg)

Ester Hernández uses witty appropriations of cultural icons to convey the Chicana experience and advocate for marginalized people, particularly farm workers. An icon of the Chicanx movement, Sun Mad draws on the artist and her family’s experiences living and working in the San Joaquin Valley. After learning that the water in her hometown had been contaminated for decades, she created the work to express her outrage at the unthinkable damage to her loved ones and community.

Her powerful image satirizes the iconic logo of Sun Maid, a privately-owned cooperative of raisin growers whose large commercial farms dominated the area where she grew up. Hernández transformed the edenic image to convey the harsh realities of farmworker life, replacing the original smiling model with a leering skeleton. She underscored her anger with the altered slogan “Sun Mad Raisins, unnaturally grown with insecticides, miticides, herbicides, fungicides.”

One of California’s foremost craftswomen, Pamela Weir-Quiton has been active since the 1960s making what she calls “functional wood sculpture” with an emphasis on FUN. She was introduced to woodworking through a class at Cal State Northridge, where her first assignment—to make a toy—resulted in the laminated hardwood dolls Little Doll and Phyllis, named after her sister.

She was subsequently assigned to make a full-scale piece of furniture, and enlarged her wooden dolls to over-life size. The result was Sloopy, named after the McCoys 1964 hit song “Hang on Sloopy.” As the song goes, Sloopy “lives in a very bad part of town, and everybody (yeah) tries to put my Sloopy down.” As a rare woman in a field dominated by men, Weir-Quiton identified with Sloopy’s marginalized status and the towering female doll allowed her to assert her place in the woodworking field. Sloopy embodies Weir-Quiton’s skillfulness, grit, and irrepressible humor. She is also generous—her offer to donate Little Doll and Phyllis to LACMA allows us to keep the gang together.

Lia Cook is a California native who has been at the forefront of the textile art field. She has expanded its formal scope, developed new processes and techniques, and combined artistic concepts with cutting-edge technologies. After studying at UC Berkeley in the 1970s, she remained in the Bay Area, serving on the faculty of the California College of Arts from 1976 to 2016.

Cook chose to work in the area of textile art because she believed it had been marginalized in the conceptually-oriented art world of the 1960s and had deep potential to speak to women’s issues. As a result, her work often treats textiles as subject—they are textiles about textiles. Tunnel Four is the last and most ambitious in a series of pocket and tunnel pieces which she began in 1984. She started by creating a piece with woven “pockets,” based on the simple textile form. Once she achieved this, she was determined to create fully self-supporting 3-dimensional “tunnels.” Cook has been recognized by East Coast institutions since the 1980s, so it is long overdue for LACMA to represent this influential California artist. Tunnel Four is a rare early work that allows us to more fully tell the story of California fiber art.

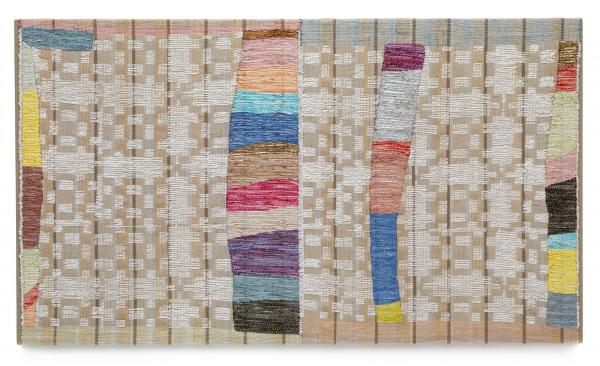

Christy Matson, a student of Lia Cook, creates woven wall hangings that integrate a painterly sensibility with the structured nature of weaving. Matson met Cook at the Jacquard Center in North Carolina and began to study with her at the California College of the Arts. Cook had developed expertise in digital weaving in the 1990s, using the Jacquard loom, which is often considered the precursor to the computer because it works on a binary system—on or off, 0s or 1s. Matson mastered the art of digital Jacquard weaving, embracing the ability to combine her painterly instincts with advanced technology. Following a seven-year period teaching at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she now lives and works in Los Angeles.

Like Cook, Matson envisions herself as a painter working in textiles. Her richly colored, ethereal works begin as watercolor studies which she translates into the binary code of the digital Jacquard loom. The geometric background pattern of beiges and whites references historic American overshot coverlets, a form which reached its zenith in the 19th century, especially in Appalachia, where Matson first learned about Jacquard weaving. Matson overlays the overshot design with beautiful regions of color that interrupt the highly structured pattern of the overshot, lending the work vitality and uniqueness. It’s like her own signature on top of the overshot pattern. Together, Tunnel Four and Overshot Variation 3 enrich LACMA’s California design and craft collections and adds the work of two more important California women to our holdings.

The curatorial team is already planning to exhibit these exciting new acquisitions in upcoming projects, such as an international touring exhibition of 20th-century California design drawn exclusively from LACMA’s extensive holdings. We look forward to sharing and studying these wonderful artworks in the years to come.