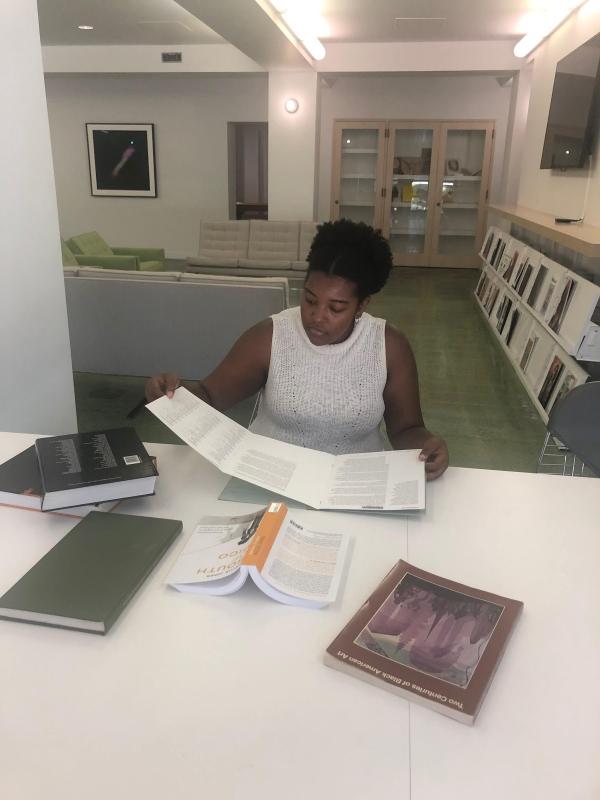

As an Andrew W. Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow, I have had the opportunity to work alongside my mentor Stephanie Barron, LACMA’s Senior Curator and Department Head of Modern Art, for the past year learning about the role of a curator in a large, encyclopedic museum. The goal of the fellowship is to encourage undergraduate students from diverse backgrounds to pursue careers in the curatorial field through support and training in the skills and thought processes necessary to be a good steward of a collection, as well as an innovative thinker. Being a part of the museum has given me access to resources that are only easily accessible to employees. I can ask questions that require deep research, and devote time to assisting LACMA staff in finding the answers.

A year prior to becoming one of the 2018–20 Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellows at LACMA, I interned in the museum’s exhibitions department where I helped to reorganize the office’s library. While organizing catalogues, I discovered quite a few exhibitions that I didn’t know had been presented at LACMA. One of the publications that stuck in my mind was Two Centuries of Black American Art. This discovery proved to be an entry point into my research of how LACMA’s exhibition programming has evolved from the museum’s opening in 1965 to today.

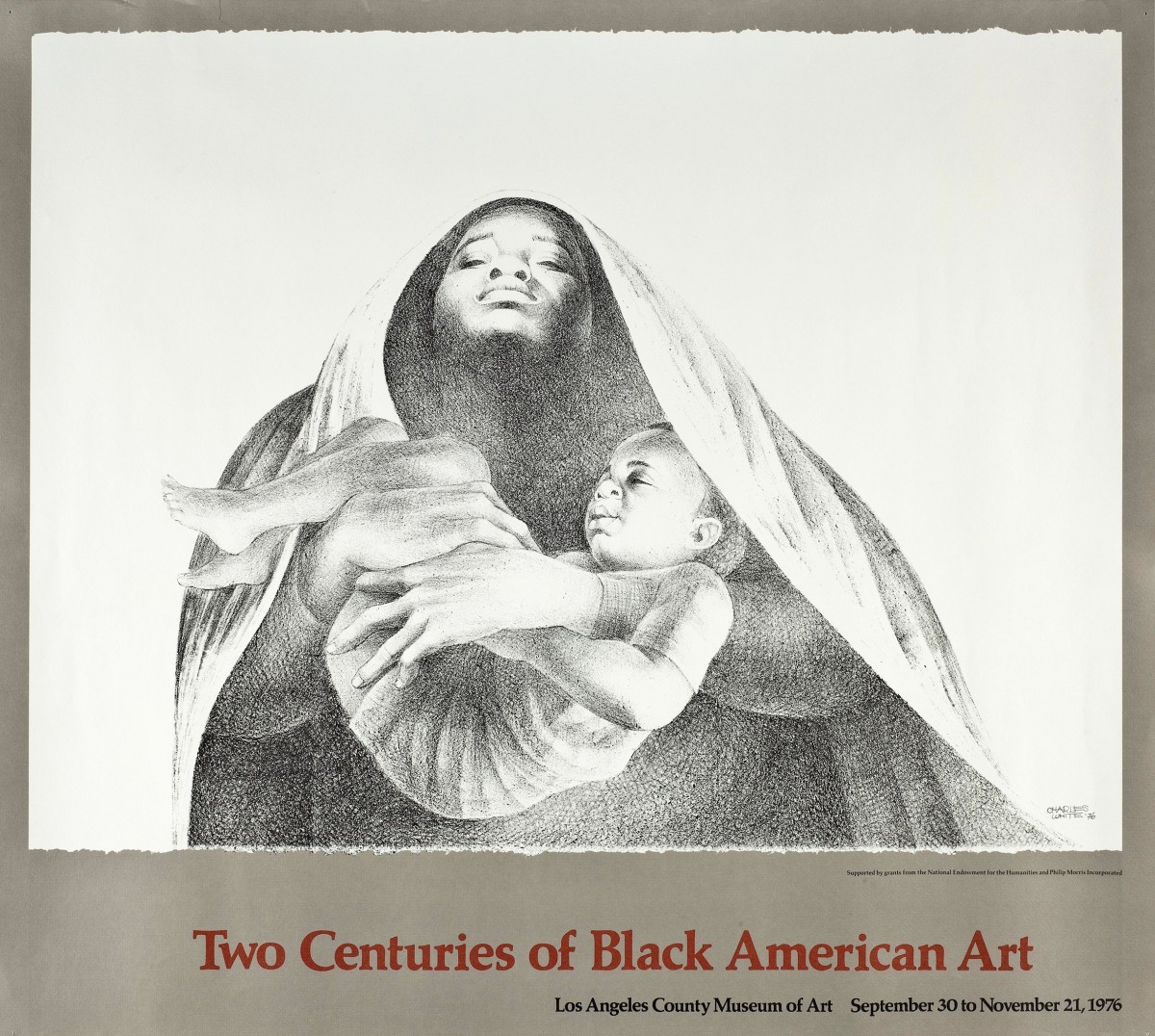

Opened on September 30, 1976, Two Centuries of Black American Art focused on works by Black artists created from 1750 to 1950. Presented as a way to commemorate the nation’s bicentennial year, the exhibition aimed to create a revisionist history, acknowledging 200 years of “forgotten” art history, which until 1976 had not been celebrated for what it was: American art. The more than 200 works and 63 artists represented by the exhibition are a testament to the museum’s desire to expand the canon. One of the first comprehensive surveys of African American art, the exhibition also traveled to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum, reflecting a shared desire for a different kind of exhibition—one that was undeniably for (and by) Black audiences. But who in the museum led the pursuit of a “for us by us” exhibition of Black art? What was the inception of this show and how was a show of this magnitude supported, both institutionally and publicly? I quickly learned that these were not simple questions to answer.

After taking a seminar titled “Art and Activism in the Archives” at the University of Southern California, I was drawn to explore the idea of the encyclopedic museum as a living archive—constantly evolving but always striving to educate the public and engage museum audiences to maintain an interest in art and history. While researching Two Centuries of Black American Art, LACMA’s institutional and exhibition history became important to understanding the show’s origins. This was especially true given the state of racial tensions in Los Angeles and heightened distrust in cultural institutions within the Black community when the exhibition was presented.

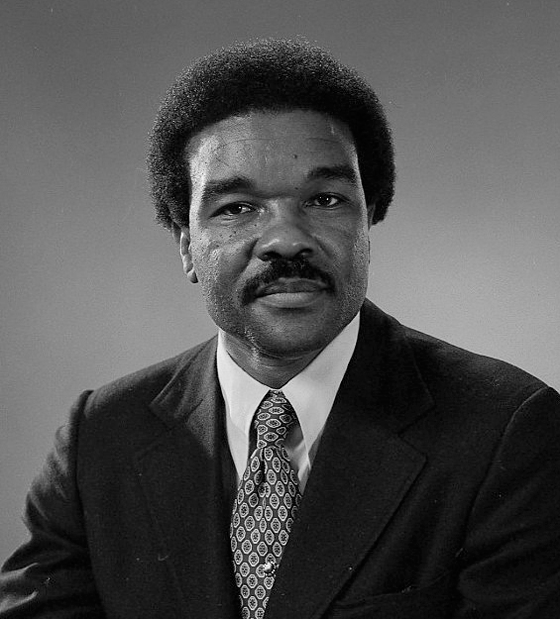

During my research, I was lucky to come across the webpage, Two Centuries of Black American Art: Who’s Who. This treasure trove of biographical information revealed key figures in the conception of the exhibition, including the guest curator, Professor David C. Driskell, who was brought in by LACMA’s then director Kenneth Donahue. Additional planning material about the exhibition, which I found on LACMA’s website, included the checklist, the press release, and reviews of the show. Although insightful, what I really yearned for was a thorough narrative of the socio-political landscape that LACMA was a part of around the time of the exhibition.

Thankfully, there are scholars who proceeded me who had already done the bulk of the archival work. I utilized South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s by Kellie Jones and Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum by Bridget Cooks, books by two scholars who seamlessly blend together institutional and public histories. To develop a clearer history from the LACMA perspective, I was able to access the archives with the guidance of archivist Jessica Gambling who spent time in the research library with me, sifting through boxes of uncatalogued material. Through these sources, I discovered the individuals who made vital steps toward a more inclusive exhibition program at LACMA.

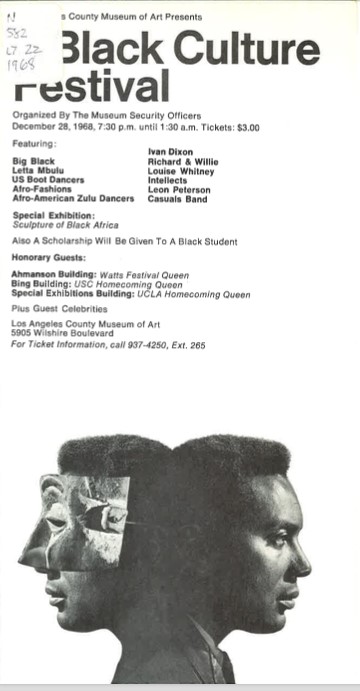

Interestingly, one of the first steps toward an embrace of diverse programming at LACMA came from the museum’s predominantly Black staff of gallery attendants and security officers. In 1968, low attendance figures for the exhibition The Sculpture of Black Africa: The Paul Tishman Collection forced museum leadership to develop a solution to bring people into the museum to see the show. This led to the organization of a full day of programming to bring members of the Black community to LACMA. Black employees utilized funding from the museum and an extensive network of artists, musicians, and media connections to organize a massive one-day symposium, called A Black Culture Festival. The event included live music, dance, and a fashion show of African designs to emphasize the connection between contemporary Black culture and the African cultures represented by the sculptures on view in the Ahmanson Building on LACMA’s campus.

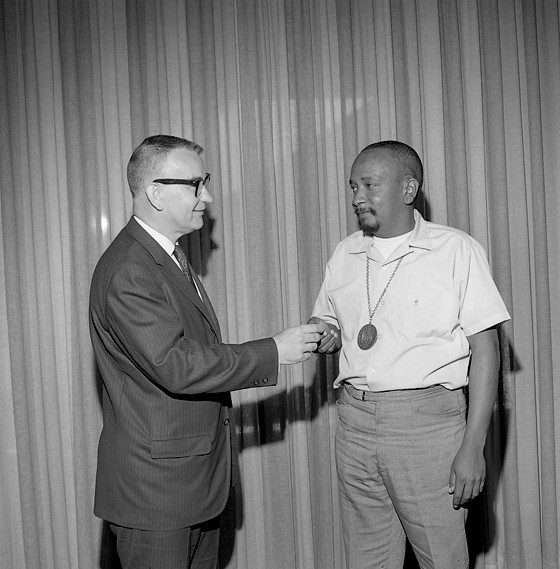

Nearly 4,000 people from around Southern California attended the event. In her book, Cooks states that the heads of LACMA’s security, Sidney Slade and Sergeant Knight, received a commendation from the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for their “unique contribution toward broadening community participation in the Museum.” The original brochure from the event, as well as photographs from the festival, and negatives from the creation of the promotional image (taken in LACMA’s photo services department), are available to view in LACMA’s archive.

Although short-lived, the museum security officers group opened the door for many Black Angelenos to become involved in the museum, including donors and collectors. Director Kenneth Donahue speaks about this phenomenon and the museum’s struggle to represent the Black population in his oral history (1980), remarking that “[the programming] all began with the Tishman show and a concerted effort to bring Black people into the councils and at the time to bring them into the board of trustees.” The trustees whom Donahue referred to, Robert Wilson and Charles Z. Wilson, went on to become the champions and fundraisers for Black art at LACMA in the 1970s, especially for Two Centuries of Black American Art.

Without this thoughtful mobilization from LACMA’s Black employee base, there is a possibility that the museum’s administration would never have come to include these individuals in the outreach efforts for the show, thus funding and support for later exhibitions of Black art would arguably have been further delayed. By demonstrating the existence of a culturally interested and active Black viewership for LACMA, the museum security officers paved the way for later programming and exhibitions proposed by Black organizers from within the museum, including the 1971 exhibition Three Graphic Artists, the 1972 exhibition Los Angeles 1972: A Panorama of Black Artists, and ultimately, Two Centuries of Black American Art in 1976. The festival’s success also led to the creation of the Black Arts Council, a group formed by LACMA employees Claude Booker and Cecil Fergerson focused on supporting Black art and artists in Los Angeles and making the museum more accessible and welcoming to the Black community.

The documents housed in the museum’s archive speak to the power of LACMA’s Black staff members and their ability to work from within the institution to dismantle racial hierarchies. However, those documents that were not kept or have been lost tell an equally riveting history of the exhibition and of LACMA institutionally. The challenges I faced in finding detailed and recorded evidence of these contributions to LACMA’s history were significant. After corresponding with LACMA archivist Jessica Gambling, contacting the David C. Driskell archive in Maryland, and reviewing countless hours of oral histories, I am acutely aware of the erasure—however unintentional—of these individual’s labor and influence. In the Director’s Foreword of the catalogue for Two Centuries of Black American Art, Kenneth Donahue did not acknowledge the contributions of the security officers nor the Black Arts Council, despite his praise of the groups retrospectively. David Driskell, however, does acknowledge briefly the Black Arts Council but not the security officers. Through this research, I am reminded of the necessity of the archive, which serves as a guide for discovery and clarification of complex histories. In this way, the archive, despite and because of all of its omissions, became essential to my understanding of LACMA’s institutional legacy.

The Andrew W. Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship gave me a better sense of how LACMA is building on its commitment to diversity and inclusion in the museum's permanent collection and exhibition program. Over the past year, LACMA exhibitions have ranged from Sri Lankan art to Central Asian ikats and contemporary art from China to shows focusing on celebrating the legacy of African American artists both locally and nationally. Upcoming solo exhibitions on Betye Saar and Julie Mehretu, as well as the recently closed Charles White retrospective, demonstrate an investment in representing communities historically ignored by art institutions. To observe this shift happening in LACMA’s programming alongside exhibitions across the city such as Soul of a Nation at The Broad allows me and other future curators unprecedented exposure to modern and contemporary art by Black artists that is not always included in academic coursework. Knowing LACMA’s history with the subject allows me to appreciate the journey to get to this point even more, inspiring me to incorporate the archive as an essential part of my budding curatorial practice.