Beyond Line: The Art of Korean Writing, on view in the Resnick Pavilion, focuses on the history of Korean writing and calligraphy, long considered one of the highest art forms in Korea. It is the inaugural exhibition to emerge from The Hyundai Project: Korean Art Scholarship Initiative at LACMA, a global exploration of traditional and contemporary Korean art through research, publications, and exhibitions. In this interview, exhibition co-curator and LACMA assistant curator of Korean art Virginia Moon talks about the exhibition and what Korean calligraphy says about the people who created it.

What was your approach in curating this exhibition?

What comes to mind for most Koreans when you say there is a calligraphy show is a small room full of scrolls and Korean grandfathers drinking tea, smoking, and patting each other on the back. But this isn’t your grandfather’s calligraphy show.

With this show I am trying to push the concept of what it means to create and live calligraphy. We’ve included classic examples of Korean calligraphy, but also examples of calligraphy written on different media—ceramics, lacquer, metal, wood, and more. I wanted to show not just different styles of calligraphy, but also the various ways Korean people have chosen to use it and why.

Each section of the show is a mirror of the time period in which those works were created, as well as the different behaviors, customs, and attitudes of each particular group of people in society. Ultimately this exhibition seeks to reveal the humanity and evolution of the people on the peninsula. Through writing, the show tells you who these people were and are. In a lot of ways, there is nothing more personal than a human being taking ink to paper.

Can you elaborate on the different sections of the show and the time periods covered?

The sections span from prehistoric times to the contemporary, which is a statement in itself, because nearly all Korean art exhibitions shown in the United States tend to stop at the end of the Joseon dynasty. I felt very strongly that we had to take it all the way up to the present day.

What connections can be drawn between the different time periods represented?

One great example is how the Royal Calligraphy gallery puts classical calligraphy in direct dialogue with a contemporary work. In those days, the kind of royal you were and your integrity and honor were thought to be revealed in your writing.

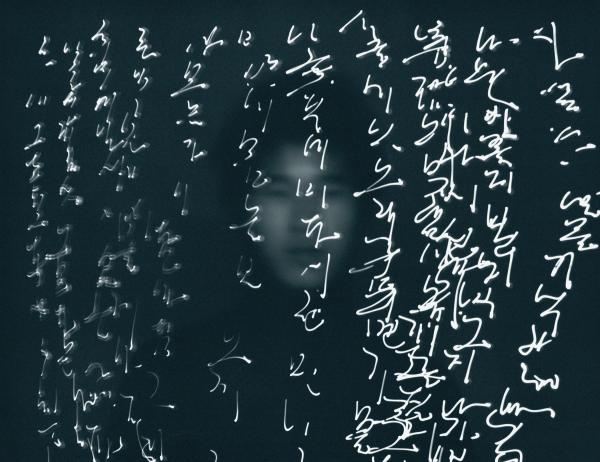

I reached out to Jung Do-Jun, a contemporary artist and probably the most renowned official calligrapher in Korea. I asked him if he could produce a commissioned work for the exhibition in the style of the royals. As it turns out, that is his specialty developed over the course of six decades. He produced an eight-scroll work based on a Chinese quatrain with parts by Tang Chinese poets Li Bai (701–762) and Du Fu (712–770) written in cursive script by King Seonjo (r. 1567–1608). To incorporate Chinese poetry was a sign of great learnedness and expected of the royals. Jung’s practice of “copying” is quite common in calligraphy, both as a learning method and as paying homage to the person who wrote it.

Tell us about the invention of hangeul.

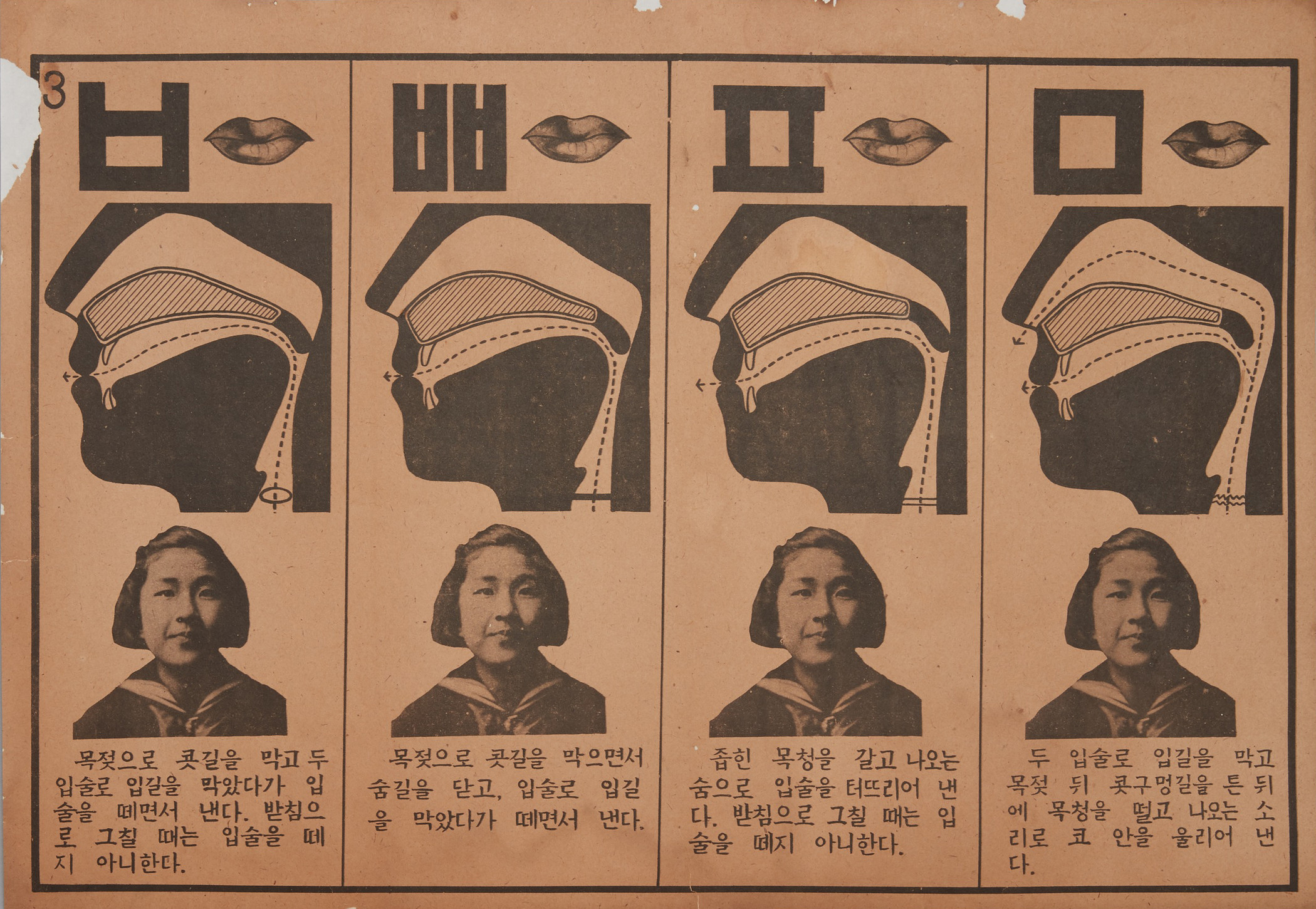

The advent of hangeul in 1446 under King Sejong’s reign was a game-changer. Up until the middle of the 15th century Chinese characters (hanja) were the only mode of reading and writing. Women and slaves were not expected to learn hanja and were largely illiterate. Hangeul was devised as a scientifically based phonetic language—the shapes of a character are based on the physical form of the inside of the mouth when the sound is made. The official debut in the royal court in 1446 was presented in a woodblock-printed book known as the Hunminjeongeum. A facsimile is in the show. Since only two genuine copies exist in Korea, and given the rarity of this manual, it is very understandable that they would not want to lend it outside of the country. The Kansong Museum in Korea, which possesses the two originals and owns Korea’s most renowned artworks, lent us an exact facsimile, which is displayed in the exhibition for the first time in the U.S. With hangeul, Korea finally had its own language. King Sejong intended the language for the entire country, but it would be another five centuries before the practice would be broadly realized. Initially, the women in the court embraced it, writing mostly personal letters. The men had to learn how to write in hangeul to their wives.

There’s also a case study in the exhibition about Gim Jeonghui. Who was he?

Gim Jeonghui was, and continues to be, hailed as the greatest Korean calligrapher of all time. He lived during the Joseon dynasty from 1786 until 1856, and he mastered every single calligraphy style from China. In his older age, while exiled in Jeju Island, he was able to synthesize his own style. Up until that point, calligraphers judged the quality of their own writing on how well they could copy the great Chinese calligraphers. Gim was able to invent his own style named Chusache after his sobriquet, Chusa. A wide range of styles are in existence and we dedicated a gallery to show as many of them as we could.

Are there any works you’re especially excited to include in this show?

To me, one of the most invaluable and amazing objects, and yet, the most humble-looking ones, are the slave letters. We have two, and this is the first time there is tangible proof that there indeed was a slave (nobi) class that was quite active in society. In many renditions of Korean history, the nobi class in Korea is described in generalities. There was not much physical evidence that could be tied to the activities of individual slaves. So the scholarship on nobi has been somewhat limited. I’m so proud that we were able to secure these two letters, which are being shown outside Korea for the first time.

You also said the exhibition goes up to the present day. How do you relate contemporary works to all of these historical examples?

Emerging from the early modern period and into today, calligraphers started to be concerned about the future of calligraphy and questioned how to keep the legacy of calligraphy alive and make calligraphy modern. Some of those experiments are in this section. We also have a digital work by Ahn Sang-soo, the father of graphic design in Korea, questioning script and its future.

These artists break all the rules. Artistically, that is a heroic thing to witness. I have the greatest respect for the artists, who are mostly living, represented in this section. They are aware of how far back this tradition goes, but they brought to the present the question, “Can I do more?” I hope this section leaves viewers asking more questions.

Beyond Line: The Art of Korean Writing is on view in the Resnick Pavilion through September 29. This article was first published in the Summer 2019 issue of Insider.