Have you ever become frustrated with tangled hair? So frustrated that you just want to lash out and claw at, tear, maybe even cut out, the offending mass? When doing my daughter’s hair, there have been times when I’ve felt that way. But giving in to these feelings just makes the tangles even worse!

For some, giving up and walking away is not a bad solution. But for a textile conservator, tangled masses of threads or yarns can present an exciting challenge. Bring it on! And what a challenge this project was. Costume and Textiles Associate Curator Clarissa Esguerra, was reluctant when she first showed me what can only be described as a nest of tangled threads. “I don’t know what you can do with this,” she said as she lightly picked at the mass. “Oh, please stop touching it,” I replied. “I’m sure that I can figure something out,” secretly feeling those first pricks of excitement. “You can? It would be great if we could include it in my exhibition; it’s for a section that discusses how ikat textiles are woven,” she said hopefully. “This is a section of unbound dyed warps, ready to string on a loom for weaving.”

Here’s a detail:

Ikat is a specialized form of resist-dyeing where the pattern is dyed into threads before weaving. This complex and time-consuming technique is achieved by tightly binding predetermined sections of threads to resist the saturation of color when submerged into dye baths. For many cultures, including Central Asia, India, Japan, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, this colorful form of ikat dyeing was popular.

Below is an example of a robe made from warp-dyed ikat fabric from LACMA’s recent award-winning exhibition, Power of Pattern: Central Asian Ikats from the David and Elizabeth Reisbord Collection (2019).

Returning to our bundle, for transport and storage the long lengths of tangled threads had been wrapped in tissue and placed in a clear archival polyethylene plastic bag. They were safe and stable, but certainly not attractive for exhibition.

Oh, my, it’s almost eight feet long! What did I promise to do? How much time do I have?

Before beginning a project like this, there are a few things to do first:

- Take “Before Treatment” photos.

- Using tiny fiber samples mounted on microscope slides, examine the fibers at 150x to 400x magnification to identify the fibers. The white cords that tied the mass together at seven different points were made from COTTON. The tangled yarns proved to be a natural fiber with one of the finest diameters (just my luck), SILK, and to top it off, silk holds a static charge extremely well.

- Be calm, relaxed, and do. not. drink. coffee. Steady hands are required.

Next, I formulated my plan: take apart the bundle, straighten it out, and then put it back together again. That’s an intrusive treatment, so making sure that everyone involved with this artifact and the upcoming exhibition would agree to the plan was important. Yes, go ahead, they said.

The first step was to document and carefully remove the seven cotton cords which were simply wrapped several times around the silk bundle, spaced about a foot apart. This step went encouragingly well. Despite the fact that these wrapping cords were intended to protect the silk yarns, these areas ultimately had the most silk tangling and damage. Can you spot these areas in the overall photo?

Each end of the silk bundle was knotted on itself. To start, one end was unknotted and examined. This was one of many points in the plan where I could back out, returning the artifact to its original condition. Should I go forward?

The large bundle was divided into many small groups which seemed to hold themselves together. Each group was made up of silk threads that were dyed with the same pattern of blue, red, black, and yellow dyes, along with natural un-dyed white threads. Like working on a beginner’s puzzle, this was an easy way to distinguish one group of threads from another; each group having a different pattern. In the area where the knot was located, yarns looked almost like new, so that separating these smaller bundles was fairly easy using non-serrated forceps or a knitting needle, with its blunt point.

The groups of dyed warps were carefully separated, struggling to coax any memory of adjacencies. Imagine opening a cylinder so that it lies flat. Where to cut the “cylinder?” Can I see a pattern emerge? Conservators try to let the artifact tell its own story. Am I imposing my own assumptions on this artifact, or am I respecting what it is trying to “tell” me? With time constraints and such a large volume of threads, this was both stressful and exciting at the same time. Each morning, I actually jumped out of bed and arrived at work early; that’s how excited I was about this project.

The original bundle fell naturally into two groups and it had been hoped that a clear pattern would emerge. Due to the static nature of silk, the groups of threads were kept separated from each other on the work table, but this made the pattern study challenging. Two four-by-six-feet work tables were tied together, end to end, for this project. The area around the tables became a “no breeze please” area since the silk threads were vulnerable to any movement or activity nearby. After 36 hours of untangling, here is what I had accomplished:

The repeated pattern was nine inches long. This seemed like a manageable size as I searched for the correct way to line up the groups in order.

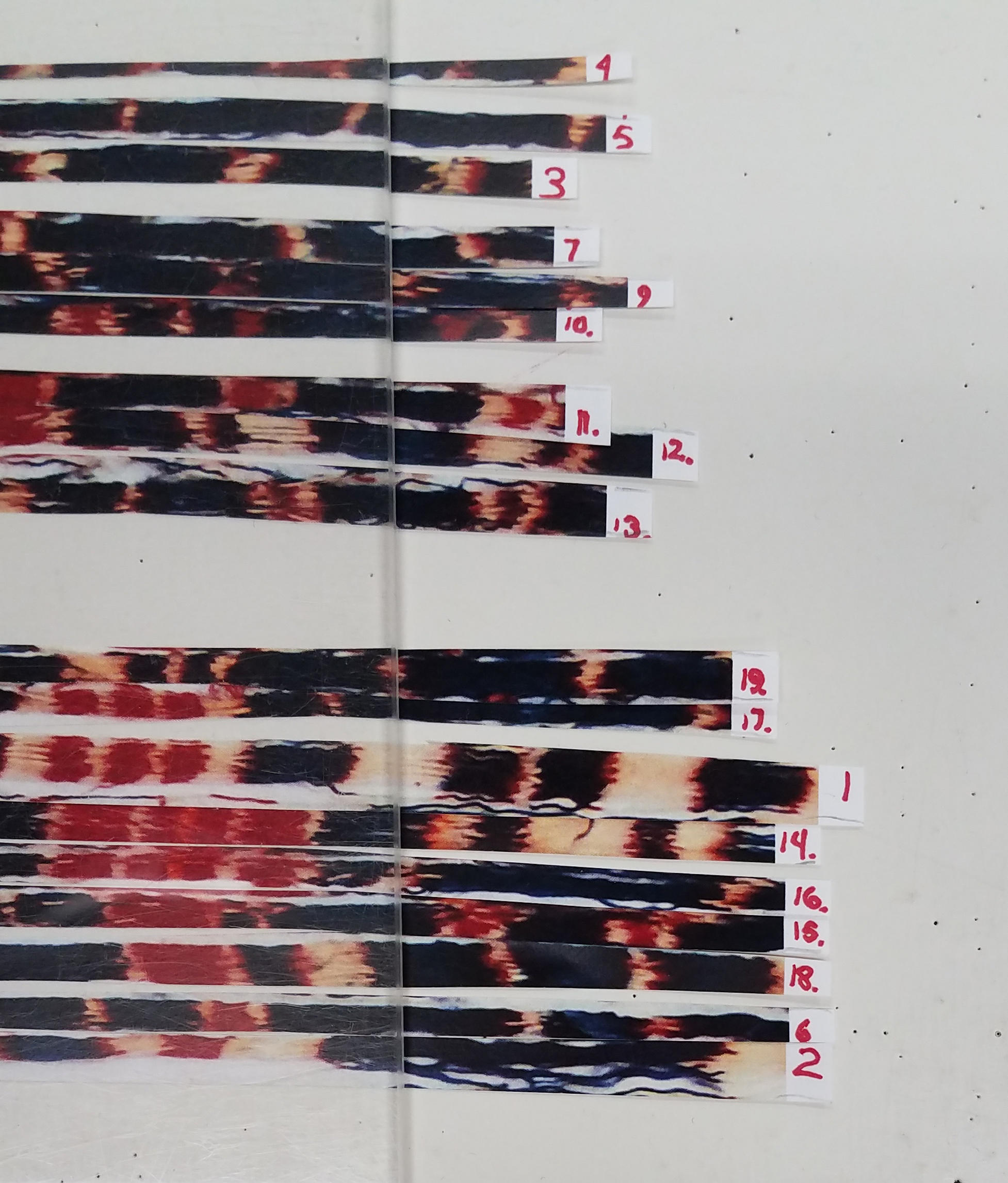

To reduce handling, a search for the pattern was done using color photographs. A segment of the bundle, including a nine inch repeat, was photographed and printed. Then I cut out (from the photos) each group of threads, resulting in long strips of paper, similar to strips from a paper shredder. Each strip was labeled so that the original order could be re-established. The paper strips could be shuffled to create an unlimited number of patterns, searching for one that made sense. Here is a detail:

After an exhaustive study, much to my surprise and disappointment, no clear pattern, beyond that of red design elements on a dark blue ground, was found. The paper strips, along with my notes, were saved so that the next detective can pick up where I left off.

With the exhibition installation rapidly approaching, the warps were re-bundled as received, wrapped with five of the seven cotton cords and partially splayed out for exhibition.

Most warp bundles dyed for ikat textiles are prepared with a specific textile length in mind. There are no “left over” warp threads. The fact that this bundle exists makes it rare; it remains an important artifact for future study.