In May 2016, I was selected as one of four interns to help launch the Costume and Textiles comprehensive inventory project in preparation for construction of LACMA’s new building for the permanent collection. In October 2016, the Costume and Textiles Department was awarded an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant to continue supporting the project and I was hired, along with Christina Frank, as an IMLS Curatorial and Collections Fellow. The grant also provided funding for a full-scale professional-grade photography set up which made it possible to produce high-quality documentary photographs of the collection that could be made available on LACMA’s Collections Online. As a curatorial and collections fellow, I was in the unique position of physically caring for the collection as well as researching it. In this post, I will be discussing our documentary photography process while highlighting a few of my favorite works in the collection, along with the compelling stories behind them.

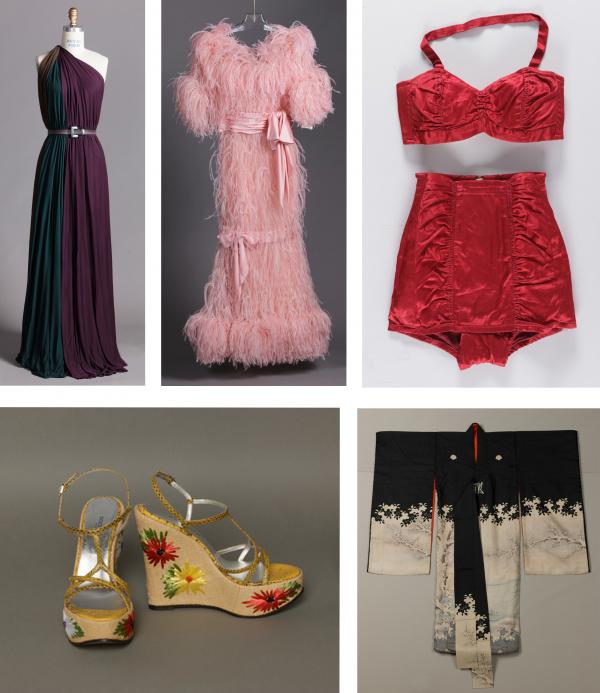

The Costume and Textiles encyclopedic collection is made up of a wide variety of objects and media, and therefore, photographing the collection required several types of set ups, including a large seamless backdrop for costumes, a small seamless backdrop for small three-dimensional objects such as shoes and handbags, a slant board for medium-sized flat textiles, and a copy stand for small flat textiles and works on paper. Photographing our largest textiles, such as tapestries, requires significantly more rigging for a shot of the whole piece, so during the scope of this project we only took detail shots of the large textiles, with plans for further photography at a later date. While the ideal way to view a costume is on a mannequin, the quantity of objects that needed to be photographed in a relatively short amount of time, plus concerns about overhandling costumes during the photo process, precluded this option for our photographic method. Most costumes that had structural integrity on their own were photographed on a hanger, like the dress in Image 1.

This dress, donated by Alexander and Anthony Cassatt (great-nephews of the artist Mary Cassatt), was worn by their mother Amanda “Minnie” Drexel (Fell) Cassatt. The sons of Minnie Cassatt donated over 80 objects from their mother’s wardrobe, many with designer or couture labels. Minnie was known for being well-dressed and clearly, as evinced by the objects given to LACMA, had very good taste. Based on our collection of objects she had a unique love of black satin bathing costumes in the 1910s–1920s, and a soft spot for gorgeous creations by the French label Callot Soeurs.

This particular dress was made by Thurn, a retailer in New York that sold both their own garments as well as garments by Parisian designers. Patronized by New York’s elite in the early 20th century, Thurn had quite a scandalous backstory. In December 1912, Thurn’s head designer admitted to the New York Times that “[the use of the fake label] was a well-known trick of the trade, you understand. We all did it, and many do yet. One cannot bring over all one’s models, and so one makes up twenty or thirty models and sticks on a Paris label. Not until then could one sell a thing.” [“It was America that Made Paris.” (New York Times, 22 Dec. 1912: 11)]. Although he didn’t admit in the article that Thurn used this practice, it surely made society women in New York question any American store that sold fine Parisian fashions. Madame Thurn was also arrested in 1909 for participating in a smuggling scheme that allowed her to bring in merchandise from Paris without having to pay customs taxes on it. It was estimated that, because of the scheme perpetrated by her and other proprietors of similar establishments, the U.S. government lost one million dollars per year (more than 28 million dollars today).

Costumes that are not best shown hanging on a hanger, like strapless dresses, or objects that would distort on a hanger, such as bias cut or knit fabrics, were dressed on a mannequin or dress form, like the example in Image 2.

On a hanger, this early 1930s Chanel dress would appear flat, but on a dress form, even if not the ideal 1930s silhouette, it is much easier to get a sense of its subtle curves and minimal structure. Donated by Mrs. Michael Blankfort in memory of her mother Mrs. William Constable Breed, the objects in this gift are some of my personal favorites, as they give a strong sense of the personal taste and social standing of the wearer. She had money to spend on the finest designers and likely went to Paris yearly to buy her wardrobe, but her style is never overdone or showy. The collection is composed of beautifully made, perfectly tailored garments, including many Cristobal Balenciaga suits for daywear and several elegant Christian Dior ball gowns for formal events. We know that Mrs. Breed must have been a favored client of Christian Dior because the collection includes several scarves, personalized with her name on them, that Christian Dior gave as gifts to only his most loyal clients.

Small accessories such as hats, shoes, and purses were photographed against a small seamless backdrop. An example of this is the miniature hat in Image 3.

This miniature hat is one of a group of 27 donated and designed by milliner Mildred Blount. Blount worked for the well known hat designer Mr. John, and is an uncredited designer and maker of the hats for the film Gone with the Wind (under the Mr. John label). Most notably, she was the first Black member, male or female, of the Motion Pictures Costumers Union, which made it possible for her to work for the film studios. After moving to Los Angeles, she designed hats for motion pictures as well as for celebrity clients including Gloria Vanderbilt for her marriage to Pat DiCicco. Several of the miniature hats in LACMA’s collection are models for the 1941 film Back Street while others may be from a larger collection of 87 miniature hats that Blount created for the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Over the course of our three-year project, we produced 10,500 photos and have been able to share 8,000 of these new images with the public on LACMA’s Collection Online. We would like to give special thanks to the LACMA Photo Services Department, who are responsible for the beautiful professional images found on LACMA’s website, in exhibition catalogues, and in numerous other places. They were instrumental in training our team in photography and photo processing, guided us through the Photoshop process that we used to edit the documentary photographs, helped us put together the photo set-ups, and were always happy to assist us with any troubleshooting we needed during the entire process. I am so proud of the quantity and quality of images we were able to produce during this project. In this difficult time of a global pandemic, I’m very glad that we could contribute a little bit of art and beauty to the digital world.