Senior Art Preparator Gerardo Arciniega, who goes by Shorty, began his journey at LACMA in 2010 installing Egyptian sarcophagi in the museum’s permanent collection galleries. Since then, he has worked with other members of LACMA’s Art Preparation and Installation (API) department to meticulously install and deinstall thousands of artworks a year from LACMA’s collection and from collections around the world.

Shorty is relentlessly committed to bettering his craft. This profile will explore how and why Shorty entered the art preparation field, and highlight his work as one of the people responsible for making art available to the public in LACMA’s galleries.

Shorty was born and raised in Watts, a neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles. At home, one activity Shorty enjoyed was fixing cars, bikes, and other equipment for his family and others in the neighborhood. He learned early on from his working-class Mexican immigrant parents how to make do with limited financial resources and technical craftiness. His dad taught him how to sand down spark plugs, an essential part of a car engine, in order to eliminate the rust. This tactic would enable the engine to live for three or four months longer.

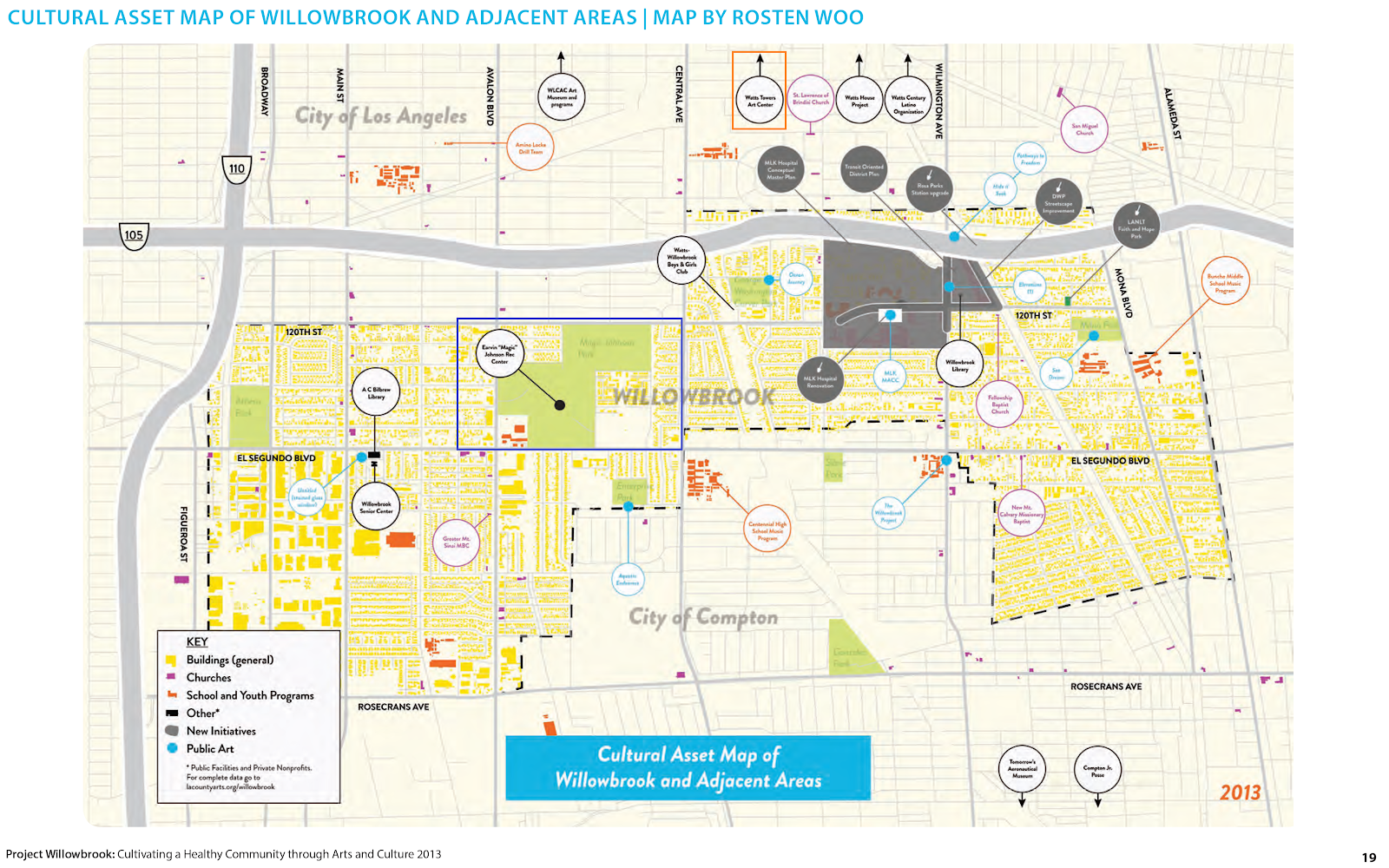

When he was not at school, Shorty played soccer in the streets or baseball at Will Rogers Park (now known as Ted Watkins) on 103rd and Central with other kids in the neighborhood. He would also bike around landmarks like the Watts Towers and other neighborhoods in South Central. During a few summers, he and his friends would translate on behalf of his Spanish-speaking neighborhood while selling watermelons at Magic Johnson Park in the adjacent town of Willowbrook. Regardless of activity, the street lamps beginning to light were his clock indicating it was time to go inside and get ready for dinner. He has passed his love of baseball and the Dodgers on to his three kids.

Another important aspect of Shorty’s childhood were barbecues at his home. “Our block was the place to be. If you weren’t there, you were missing out,” Shorty recalls. “Carne asada on the grill, music bumpin’, friends and family having a good time together. Even if someone was having a bad day, it was important to laugh and have fun.” Barbecues were a mode of building positive, lively social environments where family and friends took care of one another.

This investment in community morale, in addition to both a keen interest in observing his surroundings and hands-on problem solving, carried over into his career as an art preparator.

One of Shorty’s childhood friends, Gonzo, connected him to a supervisor at ProPack, an art shipping company, in 2002–3. Intrigued by and unclear as to what art handling entailed, Shorty signed on to become an art handler for the crating company. ProPack provides art packing, storage, and transportation services to museums, galleries, and private clients. Shorty was responsible for packing, unpacking, transporting, installing, and deinstalling artworks all over Southern California. On any given day, Shorty would deliver art to clients in San Diego, Palm Springs, and then Malibu. ProPack served as a training ground for Shorty to explore different techniques in art handling and gain exposure to imperative engineering and safety protocols such as Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) guidelines.

It was at ProPack that Shorty affirmed his interest in working with art. While art preparation skills are transferable to different professions and sectors, art installation affords Shorty the opportunity to handle artworks with different materialities and cultural contexts. Every day there are new tactical challenges of making an artist’s vision come to life.

Gonzo recommending Shorty for the job was part of a code in Shorty’s friend circle. Before that, Shorty connected Gonzo and another childhood friend, Neto, to his former employer Vintage Trucking. After starting at ProPack, Shorty secured a job for Neto at the company. This system of looking out and being looked out for was how Shorty secured a job at LACMA.

In 2010, Shorty received a call from Greg, an art prep buddy who worked with Shorty through ProPack. Jeff Haskin (the former head of API) mentioned to Greg that LACMA needed to fill an art preparator position. Unbeknownst to Shorty, Greg immediately recommended him and Shorty had an interview the following week. The job at LACMA would provide Shorty with the ability to shift away from driving all over Southern California with a varying cast of preparators, and in turn, he could focus on building a community with other preparators, conservators, registrars, museum security personnel, and other staff. He could also be a part of transforming one museum campus with art day in and day out.

Once at LACMA, Shorty joined veteran LACMA art handler Edwin Menendez’s exhibition gallery installation team. Since then, Shorty has developed a signature uniform (a Dodgers hat and pencil behind the ear) as well as a reputation for enlivening the mood of any place he goes. This reputation stems from his workplace philosophy of finding common ground with and expressing compassion for the people he works with, regardless of how stressful the work is. Shorty recalls an international courier visiting LACMA to oversee the installation of one artwork from her respective institution. “All morning, the courier was short with people. As soon as I had a chance to work with her, I cracked a joke (lovingly) about another preparator and started chatting it up with her about the art and where she works. The courier was cool the rest of the day. No more issues from that point on.” Bolstering community morale and interpersonal relationships are strategies for Shorty to care for his team members as they all handle stressful situations involving fragile, sacred, and valuable objects.

The spatial awareness Shorty exhibited as a kid biking around South Central now takes the form of analyzing how to mitigate potential risks in moving artworks safely. Take, for example, the deinstallation of British-Trinidadian artist Zak Ové’s The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness in the Cantor Sculpture Garden. The deinstall required, in part, moving Ové’s sculptures from the cascading steps onto the ground. Mind you, the steps were closely surrounded by potted plants and it was a narrow staircase. As the lead preparator for the deinstallation, Shorty consulted with Assistant Registrar Dawn Turner and other preps weeks prior to the deinstall to determine what the best strategy was for safely maneuvering Ové’s sculptures over the Rodin statues and plants. They agreed on using the telescoping boom forklift, rather than brute strength, to hoist the sculptures. This machine provided the extended reach needed over the stairs, so that the sculptures and base plates didn’t have to be carried by hand down the stairs, which would have been risky for the art handlers and the artwork. Utilizing the telehandler required Shorty and the team to take into account numerous safety regulations and engineering principles.

Bearing these and other guidelines in mind, Shorty and his team first transported the telehandler to the garden, much to the amusement of visiting middle school students documenting the movement via Snapchat videos. Next, Shorty, Art Preparator II David Foster, and Art Preparator I Jack Baker used materials like the lifting slings, additional clamps, and volara foam to attach one of the figures to the forklift.

Competing with the telehandler’s relentless industrial rumbling, Shorty utilized both verbal and hand signals to direct the lift’s operator, Senior Art Preparator Michael Price, through the process of moving the artwork. He was fully concentrated, ensuring the safety and well-being of both the team and the object.

This scenario is a testament to how Shorty and the other preparators must track their own body positioning and that of others, professional guidelines, and their immediate surroundings as they maneuver a single artwork.

Even as a veteran of the art preparation field with 17 years experience, Shorty continues to find opportunities to build his technical know-how. These experiences include taking courses in Pomona for rigging, beginning to courier LACMA artworks to other institutions, and signing up to attend a future rigging workshop in Delaware hosted by the Preparation, Art Handling, Collections Care Information Network (PACCIN, a professional organization for art preparators and collection technicians). Like the professional support network he established with childhood friends Neto and Gonzo as well as Greg at the Broad Art Foundation, Shorty is invested in exchanging opportunities and tips of the trade with emerging preparators through the Broad Diversity Apprenticeship Program (DAP). As a DAP mentor, he gives guidance to his prep apprentice mentee about their career path and also helps welcome them into the profession, listen when things are difficult, and more broadly advocate to make our workplaces more inclusive.

Jasmine Tibayan, former Broad DAP apprentice and now LACMA Art Preparator I, notes in working with Shorty during her fellowship: “When I first interacted with Shorty through DAP, we were already collaborating on how I could be a more efficient art installer based on my small notebook with drawings and math formulas. Shorty would create spaces to share his expertise, encourage my growth, and celebrate our success in every LACMA project we worked on together.”

The paradox of art preparation is that when done masterfully, it should leave the audience with no trace that a person or team even installed it. The artwork appearing “out of the thin air” in the gallery space allows the viewer to get lost in the majestic and mysterious qualities of the objects, rather than focus on concerns like the stability or safety of the artwork. Yet that means the labor, rigor, and expertise that Shorty and other preparators perform each day to ensure each artwork’s safety can become invisible.

Revealing glimpses of Shorty’s life history serves to uplift the talent and personal background that one preparator brings to museums. Shorty’s dedication to community morale, capacity to keenly observe and discern, and ability to problem solve with the tools around him are just a few of the many qualities that make him a master preparator and an invaluable part of LACMA’s team.

When reflecting on his life and career, Shorty said, “I’ve seen Los Angeles in great times like the low-rider car club picnics in Elysian Park in the 80s and 90s. I’ve seen Los Angeles in tough times like some neighborhoods having four or five liquor stores within a quarter mile and no grocery stores in sight. But for me, and I tell my kids this all the time, what’s important is that it doesn’t matter where you come from, but it’s how hard you work to get to where you want to go.”