Artist Luchita Hurtado, whose career survey I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn is currently installed at LACMA, passed away yesterday, August 13, 2020, at the age of 99. Here, curator Jennifer King offers an appreciation of the artist.

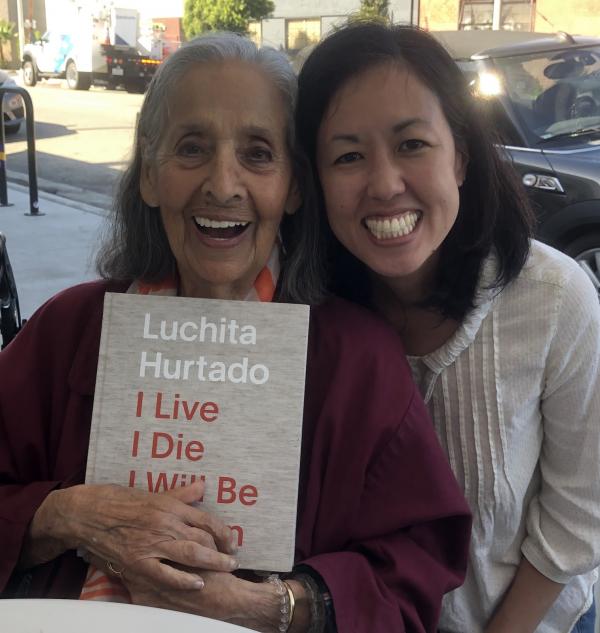

The first time I met Luchita Hurtado was over lunch at Fromin's in Santa Monica, where she was a regular. The whole waitstaff knew her by name. That level of familiarity, I came to discover, was typical of Luchita's ability to charm people. What got me was how she saw the humor in things. She had a habit of finishing her stories or observations with a slight pause and then, after a beat, a little burst of reflective laughter. Her laugh, and her perspective on the world, made it a joy to spend time with her.

Given Luchita's sociability, it's still hard for me to wrap my head around how few people knew of her art practice, considering she and her late husband Lee Mullican were a vital part of the Los Angeles art community. After her "discovery" in 2016, she inevitably faced questions about how her role as a wife and mother impacted her path as an artist, but she was always philosophical about it. More than once, when we were working on her exhibition for LACMA, she told me she felt lucky to be alive to enjoy her success. "I'm just glad I get to see it," she would reassure me about our show. Who knew, when it opened to the public in mid-February, that it would close less than a month later due to a global pandemic. I'm so grateful, looking back, for the incredible opening night gathering of friends, family, and admirers who came together to celebrate with Luchita.

I won't spend too much time here on Luchita's life story, as it's been the subject of multiple profiles and interviews. Those accounts detail her encounters with avant-garde circles in the late 1930s and 1940s—her friendships with Rufino Tamayo and Isamu Noguchi in New York; her marriage and travels in Mexico with second husband Wolfgang Paalen; her time in Mill Valley, California with Paalen, Mullican, and Gordon Onslow Ford during the years of the short-lived Dynaton group. After she divorced Paalen and settled in L.A. in 1951, she and Lee raised their sons, Matt and John, and her son Daniel from her first marriage, on Mesa Road in the Santa Monica Canyon, where their neighbors included Sam Francis, Don Bachardy & Christopher Isherwood, and Susan Titelman & Ry Cooder. In 1971, Luchita attended the first meeting of the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists; as the story goes, Luchita introduced herself to the group as "Luchita Mullican," and only when challenged "Luchita what?" by printmaker June Wayne, did she proudly answer, "Luchita Hurtado." As she told Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2017, "It became very important in my life to remember that name."

Between the attention paid to Luchita's biography, and the Cinderella aspect of her late-career success, what often gets glossed over is the achievement of the work itself. In LACMA's exhibition, the earliest artwork dates from 1942, and the most recent paintings were finished in early 2020—bookends to a remarkable eight-decade span of artistic creation. Walking through the exhibition as it moves from her forays into abstraction, to her experiments with language, to her engagements with ecology, one sees what at first appear to be different and discrete bodies of work. But what connects them all is an art practice that, over a lifetime, consistently reflected on our relationship as individuals to the world around us: be it our relationship to prehistory and ancient cultures; our relationship to nature and the environment (so eloquently summarized by Luchita's painted words "We are all a species"); or our relationship as human beings with one another, and—most piercingly—with ourselves. Throughout her life Luchita made inventive self-portraits—not just examples depicting herself in her surroundings, but also more subtle self-portraits rendered in text and metaphorical representations. Together they speak to artmaking as an insistent declaration of being—as a way of stating, to quote words Luchita patterned in paint, "I am."

"I've lived many lives," Luchita told me matter-of-factly the first time we looked at the checklist of her show together. In her recent work, images of birth were an important motif, and it's hard not to think of those paintings as her way of connecting the end of life to the beginning. Luchita was nothing if not prescient. In her Self Portrait, 1973, she embedded words that form the title of her exhibition, and read now like her final message to us:

I Live

I Die

I Will Be Reborn