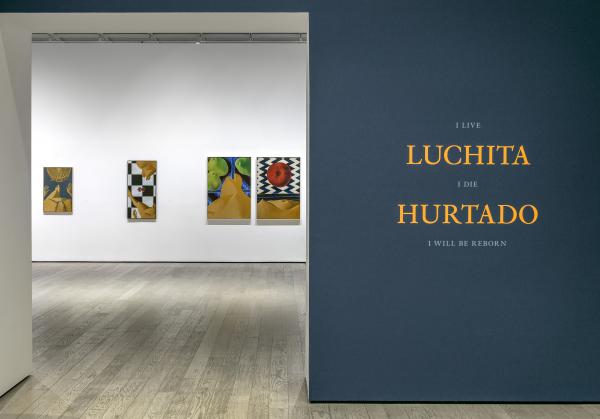

In early May, as the museum entered its eighth week of temporary closure due to COVID-19, I wrote for Unframed about the difficulty of translating in-person viewing to the virtual format of words and images. "Art is meant to be shared with the people we love," I wrote, "and for me, doing that over a screen will never be enough." Since then, however, I’ve heard from many people about their regret at not seeing Luchita Hurtado: I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn before the museum closed on March 14. Now, as we sadly prepare to deinstall the exhibition, I want to share some thematic highlights and details of works spanning Hurtado’s eight decade career.

Abstraction and Materiality

The biomorphic forms and abstract shapes in Hurtado's early works evoke a range of associations, from neolithic figurines to prehistoric rock art and automatic drawing techniques. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Hurtado regularly worked in crayon, using a method called "ink resist." For this technique, an ink wash is applied over areas rendered in crayon; because of the water-repelling properties of the waxy crayon, the ink permeates the paper only between the colored strokes. In many of these works, the contrast between dark ink wash and colored hues creates a dense and vibrant energy.

Figures

Throughout her career, Hurtado continually returned to the human figure and figure relationships. In works from the 1950s to the present, we see bodies alone and in different states of interaction—figures embracing, Mother Nature as a figure, and, in more recent works, images of birth. In one painting from this section of the exhibition, Hurtado traced the outline of herself and her youngest son John, then age four. That canvas is installed adjacent to a trio of paintings on wood completed in January 2020. Although separated in time by more than 50 years, the paintings bear strong formal affinities in their outstretched arms and the interplay between positive and negative space.

Language and Abstraction

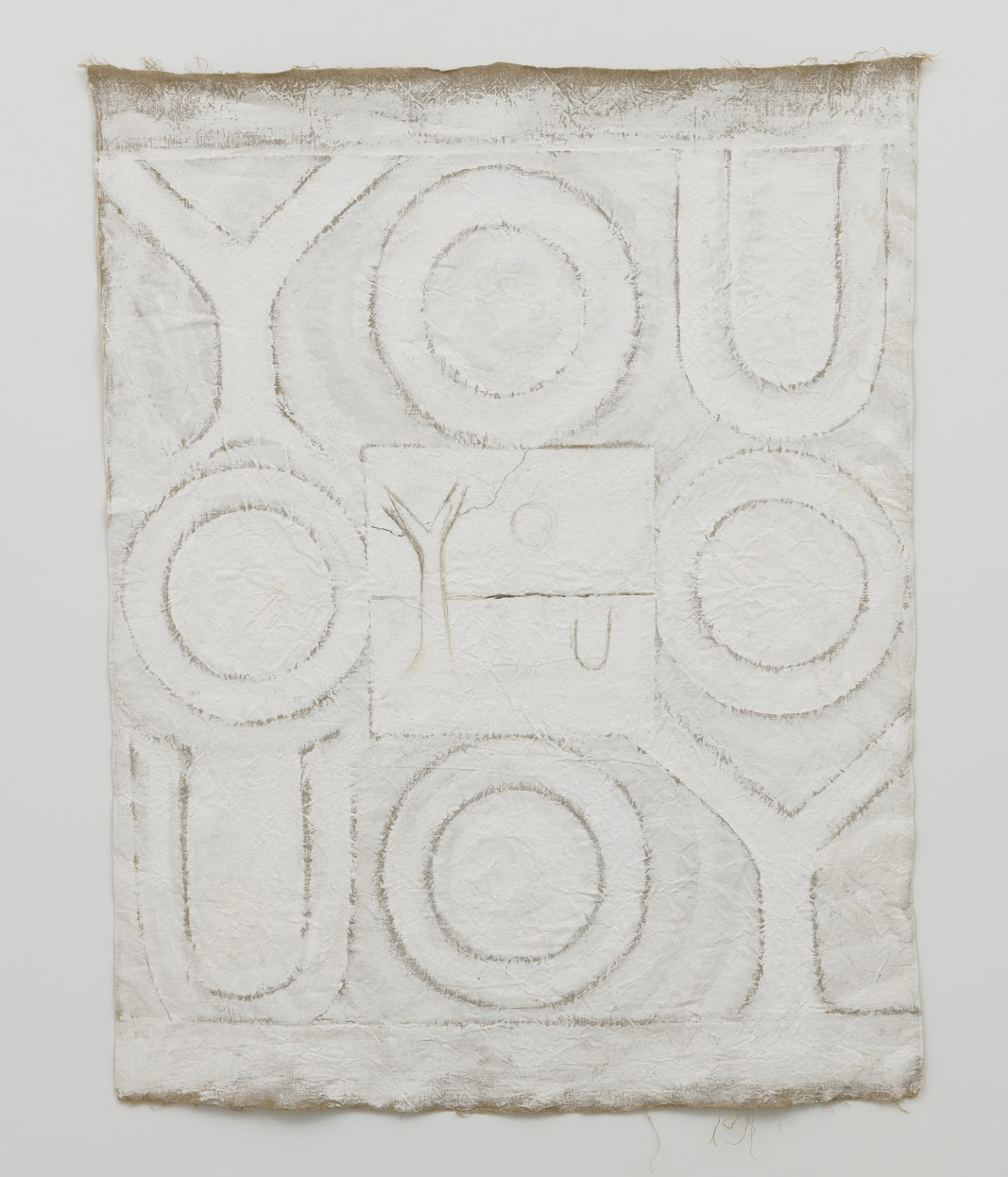

Although Hurtado's art practice took place mostly in private for almost eight decades, the one exception was in 1974, when she exhibited a group of large-scale paintings at the storied Woman's Building in Los Angeles. LACMA's presentation features a partial reconstitution of the works from the 1974 show; the paintings from this series appear at first to be geometric abstractions, but most contain embedded words and phrases. Some of the canvases Hurtado cut into strips, reconfigured, and stitched back together again. The artist has explained about the genesis of these paintings:

"I did many self-portraits. And then at one point I decided I would use letters, and I did.... I started with a portrait that said, "I am." And I decided that was as much me as my real face and figure. And so at one point I began then to write things. And I decided to cut them up and make them even more unlikely that you'd ever read what I had written. I accomplished that by cutting the painting into strips and then sewing them, and then stretching them."

In another series of works executed around the same time, Hurtado incorporated single words (Adam, Eve, Womb, You, Me) into paintings on unstretched canvas or linen.

Feathers and Sky

Hurtado has spoken of the feather as a mysterious symbol, one that retains a kind of magic through its apparent weightlessness. In some of her paintings, feathers appear to float up to the sky, other times coming together to suggest figures or facial features. In her "Sky Skin" paintings, many of which include feathers, the artist often composed the shape of the sky to resemble a stretched animal skin. The palette of her Sky Skin works were informed by the sky and landscape colors of Taos, New Mexico where many of them were painted.

Nature and Ecology

.jpg)

Themes of nature and ecology appear throughout Hurtado's work. The LACMA presentation features a selection of the numerous plant drawings Hurtado made during her lifetime, which document her deep engagement with the natural world. In them we see samples of the weeds, flowers, and trees of the Santa Monica Canyon and of Taos, New Mexico, where Hurtado and her late husband Lee Mullican built a house in the 1970s and regularly spent summers. A second grouping demonstrates Hurtado's return to environmental activism and ecological awareness, in works featuring phrases such as "No Place to Hide," "No One is Paying Attention," and "We Are Just a Species."

Self-Portraiture

In the late 1960s, Hurtado began painting self-portraits from the vantage point of the artist looking steeply downward at her own body. In some paintings we see only her feet, knees, and hands; in others we also see her breasts and bare stomach. Hurtado often poignantly incorporated everyday objects—a toy car, a ball of string, a potted plant, a drinking glass—into her compositions. In other self-portraits, Hurtado experimented with her silhouette as a compositional element. She also painted more conventional self-portraits, in which her solemn face looks directly out at the viewer. Her consistent recourse to herself as a subject speaks to a painting practice faithfully maintained during moments carved out from domestic family life.

Interconnectedness

Although Hurtado was very inventive—creating many bodies of work over the course of her long career—these themes and works are united by her consistent approach to art making as a way of connecting with the world. For Hurtado, making art was a way of reflecting on our relationships as individuals to each other, to our surroundings, and to ourselves.

Please note: LACMA is temporarily closed to the public. We are actively reviewing the possibility of extending exhibitions that are affected by the museum's temporary closure. We will announce any news about exhibitions by email, on our website, and through social media (@lacma).