While LACMA is temporarily closed to the public*, our mission remains to celebrate centuries of creativity and inspiring human endeavors. We've asked various members of the museum's staff to share which favorite LACMA artworks—from ancient to modern, from East to West, from world-renowned to more obscure—they would love to have in their homes during this time.

Just like those who have been working remotely either part- or full-time for what is now a year since the beginning of the pandemic, I have never spent so many of my waking hours in my home. I have found myself, as others have, "redoing" much of my personal space and adding more decorative elements, especially incorporating color and live plants. When I think about the artworks in the Costume and Textiles collection, there are many textiles that originally had a similar function of enlivening a personal space, especially the foliate-laden fabrics that gave people before me a moment of pleasure, especially amid sometimes difficult times.

Motifs drawn from nature have been part of homes in societies around the world for centuries. Whether for celebrations or for quiet contemplation, with patterns that are realistic or abstract, and in textiles dyed, woven, printed, or embroidered, imagery drawn from the natural world has decorated interior spaces as wall hangings, bed coverings, furniture upholstery, or more intimately, garments worn on the body. The incorporation of floral design elements in textiles can have the transportive effect of bringing a lush garden into one's private space—often signaling bounty in nature and in life. These motifs also have the power to suggest travel (something I sorely miss), with some foliate designs moving from culture to culture, being adopted as a means to display one's global interests and illustrating the world's increasing interconnectedness. Below are just a few of my favorite floral textiles from the collection:

Since the Bronze Age, Central Asians have used images of flora—particularly branching forms illustrative of axis mundi (the tree of life) with roots in the underworld, a trunk rising through the terrestrial space, and branches reaching toward heaven—to symbolize the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. By the 19th century, when ikat textile production (a technique where vertical threads are resist-dyed with a pattern prior to weaving) flourished in Central Asia, these motifs were reinterpreted into designs that mixed previously potent symbols into bold patterns. A pardah (wall hanging) used to decorate the home features a vertical stalk with curved branches also reminiscent of a ram's horn. This colorful ikat pattern was laboriously dyed with seven hues, which gave the cloth, called haftrang, or "seven color," even more prestige.

Earlier, in the 16th and 17th centuries, luxuriant floral patterns decorated the architecture, furniture, jewelry, and textiles of the Indian courts, which responded to the extensive gardens surrounding the royal palaces. Simulated gardens traveled with the emperor as he moved from capital to capital in the form of exquisitely painted tent panels, which were raised with ropes and poles around the royal tent to create a refreshing milieu of floral imagery. When introduced to Europe in the 17th century, the colors and opulent floral motifs of Indian painted cottons intrigued consumers; a voracious demand for textiles ensued for more than a century, and had a profound effect on Europe's politics and economy.

Kashmir shawls—prized for their luxurious feel, light weight, and warmth—were, by the late 18th century, in high demand in Europe, creating a design dialogue between East and West through much of the 19th century. The floral patterns and naturalistic tear-drop buta (or paisley) motifs of Kashmir shawl designs influenced imitation shawls that were manufactured in Europe, while new European designs were given to weavers in India to produce for the Western market. This shawl made in Kashmir of fine goat-fleece underdown (pashm) is composed of multiple pieces of twill tapestry adeptly stitched together to create a large, sweeping design.

This late 18th century European embroidered petticoat (skirt) features repeating patterns of flowers including tiger lilies indigenous to Asia, here worn with a short jacket called a caraco. The petticoat was embroidered across four panels of silk satin and stitched together, with each panel measuring 28 inches in selvage-to-selvage width. This corresponds to the range of specified widths for silk fabrics ordered by the British East India Company; thus, this piece was likely embroidered in Asia (probably China) for the European market.

In the 19th century, Westerners were captivated by the Japanese kimono but found the long, trailing robe impractical to wear. This imported informal "kimono" dressing gown, embroidered with wisterias, peonies, cherry blossoms, and irises, was cut shorter than a traditional kimono, to accommodate a Western woman's wider gait, and included a soft Western-style matching sash.

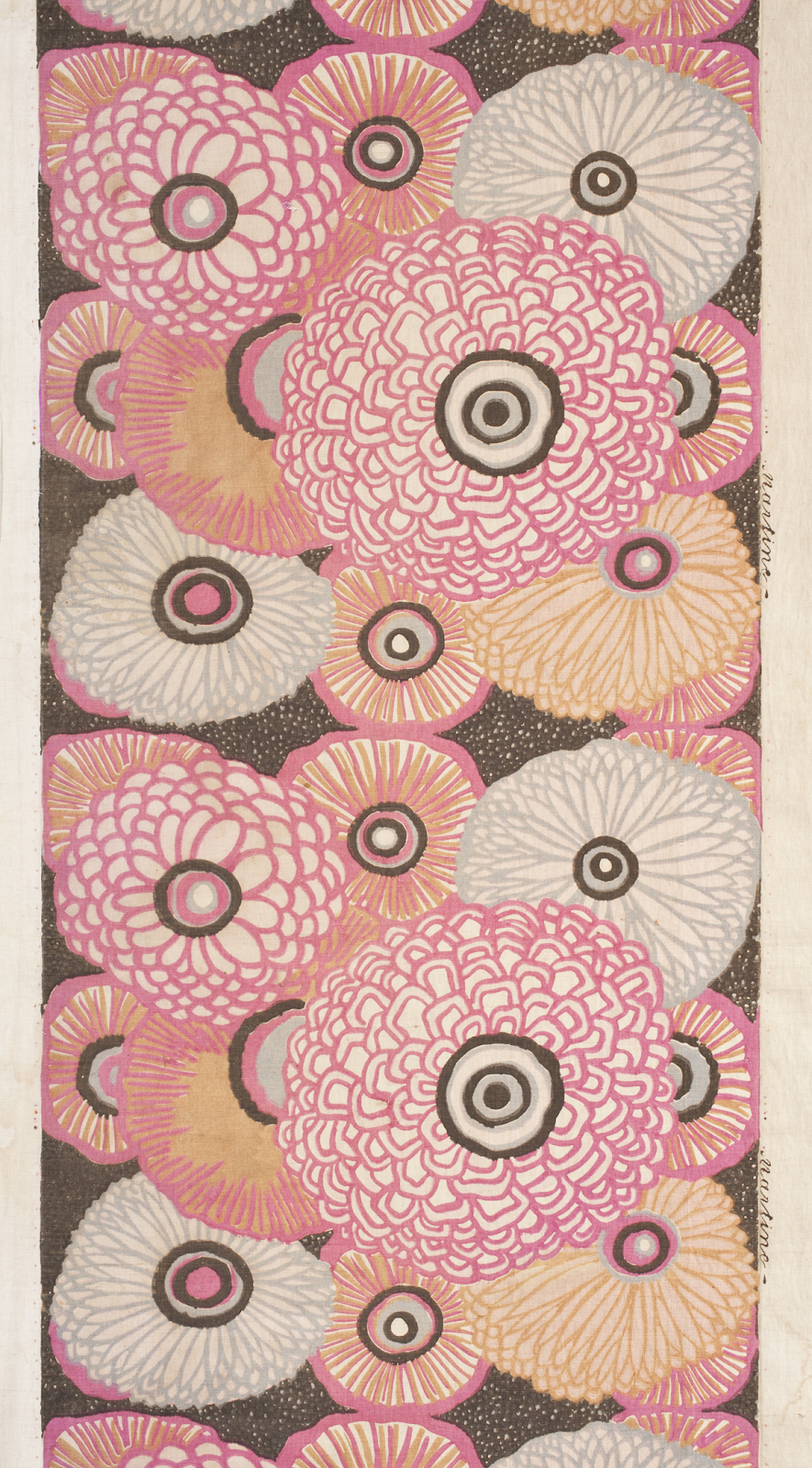

Known for the modernity of his fashion, early 20th century couture designer Paul Poiret also advocated an independent, more expressive approach to the decorative arts. He established a studio school for young girls, 13 to 15 years of age, who had experienced little exposure to academics and the arts. The spontaneous and intuitive work of the young artists of the Atelier Martine, known for their bold and joyous renderings of flowers, gained critical acclaim; their work was exhibited in 1912 at the famous Salon d'Automne, and orders for their textiles, carpets, and wallpapers came from all over Europe and the United States.

* LACMA will reopen indoor galleries to the public on April 1, 2021, in line with L.A. County guidelines for museums. Member Previews are March 26–30. Advance tickets for Member Previews will be available to reserve on LACMA's website on March 19 at 10 am PDT. Advance tickets for the general public will be available for purchase on March 25 at 10 am PDT.