"From time to time my father, Bernard Zimmerman, used to get his mail," Adam Zimmerman relayed to me over the phone this past November. "At one point, later in his life, he ended up in a shared hospital room. To his surprise, behind the curtain was the other Bernard Zimmerman."

In Los Angeles, beginning in the late 1950s, two men by the same name and of the same generation rose to prominence in the Los Angeles art and architectural scene. One an artist, the other an architect, both worked and taught in Los Angeles, both supported the city's growing architectural scene, both were involved with LACMA, and both contributed to the city's exciting position as a place of progressive thought and aesthetic theories that came to define Los Angeles in the 60s and beyond.

As part of LACMA's efforts to share work in public settings across Los Angeles County, we recently installed three sculptures at Cal State LA, including one by Bernard Zimmerman. Our object files are the starting point for any research involving a work of art at the museum, particularly if it is lesser known or has not yet been on view, as was the case of Zimmerman's John Henry. Inside this file was some correspondence from Zimmerman The Architect (on his letterhead) to LACMA's former curator of Modern Art, Maurice Tuchman, as well as articles, photographs, and information about the sculpture and the artist.

Bernard Zimmerman (1930–2009) The Architect is well known. A leading figure in architectural circles, he was a native Northern Californian who made his way south to get his masters in architecture at USC before beginning architectural work. Ultimately, he began his own firm and built an enormously influential career as an educator, helping to begin the architecture department at Cal Poly Pomona where he taught for over three decades. During the course of his career, he was deeply involved in recognizing and legitimizing the architectural milieu of Los Angeles, including co-founding the Los Angeles Institute of Architecture and Design, helping to establish the Architecture + Design Museum,¹ and in 1991, establishing the annual Masters of Architecture lecture series at LACMA. Zimmerman had a significant relationship with LACMA and with the former curator of Modern Art, Maurice Tuchman, as evidenced in the correspondence in the museum's object files. His personality was strong and attractive, but also aggressive and forthright. According to Frances Anderton, architectural critic and historian, "He was utterly convinced of the rightness of a stringent brand of Modernism—its social as well as its formal principles—and didn't hold back from chastising any designer he felt had fallen short of its ideals."²

Having no reason to believe The Architect was not also The Sculptor, we shared the information with Cal State LA and proceeded with our installation. While I was preparing a blog post to showcase this first installation at the school, as a matter of standard practice, Dawson Weber, Senior Associate, Rights and Reproductions, reached out to ask permission from the Zimmerman estate to use an image of the sculpture on our website. The reply from Lauren Weiss Bricker, Director of the ENV Archives-Special Collections, Cal Poly Pomona and the archivist most familiar with Zimmerman and his work, was quite a surprise. She wrote that she had learned that Zimmerman The Architect was not Zimmerman The Sculptor, concluding her email saying simply, "there must have been two of them."³

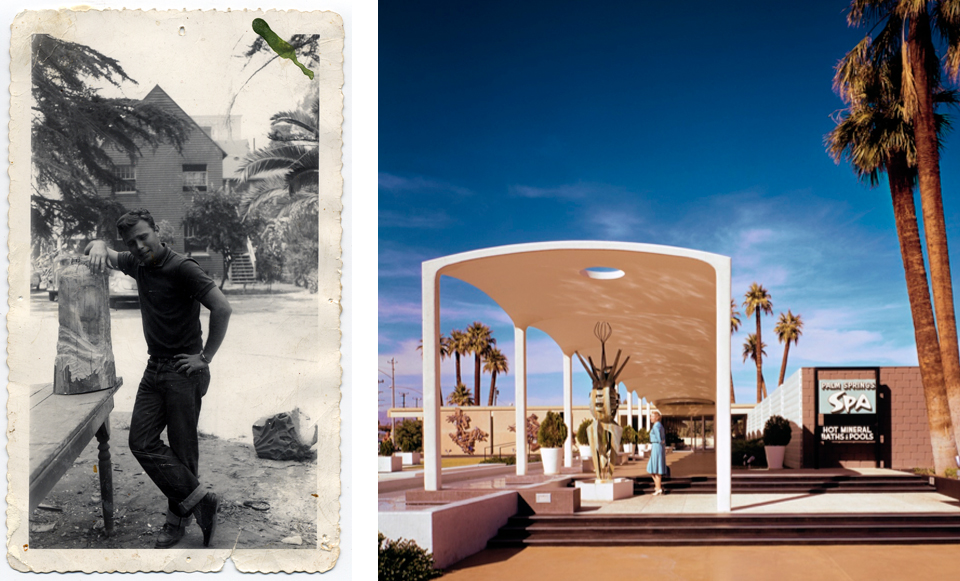

Following this new information, I began to look for more evidence concerning these two men with the same name—in particular, information that would explicitly differentiate them. Hampered by the closure of libraries during the pandemic, I turned to our local community of scholars. Our current department head of Modern Art, Stephanie Barron, remembered The Architect, but had only just started working at the museum at the time this sculpture was gifted to LACMA, and did not recall the circumstances of its donation. I reached out to a scholar in the Los Angeles architectural community, Dr. Emily Bills, and she gathered enough information from her colleagues to confirm what Bricker had said: there were, in fact, two different Zimmermans, but no one was able to point to specific evidence. In the meantime, I had reached out to The Architect's son, and I had ordered the only archival information I could find on Zimmerman The Sculptor, which was housed at the Archives of American Art. This would take weeks to digitize and send, given the protocols due to COVID-19. It was about a month after we were first tipped off to the fact that there were possibly two Zimmermans when I received a phone call, out of the blue. Adam Zimmerman had read about the Cal State installation, and wanted to clarify that his father, Bernard Zimmerman was not, in fact, The Architect, but instead The Sculptor.

Bernard Zimmerman The Sculptor is now 93 years old. Born in the Bronx, New York in 1927, he came to Los Angeles in the 1940s and had a long career in Los Angeles through which he was as dedicated to progressive and modern ideals as Zimmerman The Architect. In the early part of his career, he studied at the Otis Art Institute, as well as stints in Italy and New York. He taught for decades, primarily out of his studios, from the 1950s to the early 2000s, and participated in exhibitions at LACMA, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and the San Francisco Legion of Honor, as well as at exhibitions in San Diego, Seattle, and Portland. He was represented by the Ankrum Gallery in Los Angeles in the 1960s,⁴ and is perhaps best known for his large outdoor sculpture installations in cast bronze or welded metal in architectural settings across the Southland,⁵ including his 12-foot Dancing Water Nymphs at the controversial exemplar of desert modernism—the former Palm Springs Hotel and Spa.⁶ His artwork remains in local collections and private homes across Southern California, as well as in institutions like LACMA and the Hirshhorn.

As information across various channels materialized through digitized archives and published sources alongside the shared knowledge of a group of scholars, historians, and even family members, a clearer picture of these two men, and their contributions to the Los Angeles art scene, has formed. While a selection of the works we care for at LACMA have detailed records down to the day on which they were made—or their 200-year journey into the museum's care can be traced owner by owner—the majority of the more than 142,000 objects in our collection continue to warrant physical and scholarly attention. It is only in our efforts to display these objects—whether through our robust lending program, through cross-institutional initiatives, or through the dynamic presentations we have planned for our new building for the permanent collection—that we will continue to clarify and present the histories of these works.

¹ https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/5053-outspoken-california-a...

² Ibid.

³ Email correspondence between Dawson Weber and Lauren Weiss Bricker, 22 October 2020.

⁴ Ankrum Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Box 25, Folders 19 and 20.

⁵ Lyn Kienholz, L.A. Rising, SoCal Artists Before 1980.

⁶ For the issues surrounding the site and Indigenous land, see https://www.desertsun.com/story/life/2020/07/14/how-palm-springs-section...