Drawn primarily from LACMA’s encyclopedic collection, the exhibition NOT I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE) looks to ventriloquism as both a theme and a methodology. I spoke with exhibition curator José Luis Blondet about the ideas at the heart of the show and how voices are a useful framework for considering LACMA’s diverse holdings.

What makes ventriloquism so resonant in the context of an art museum?

Ventriloquism seems to be akin to the logic of the encyclopedic museum, in which objects are speaking on behalf of an entire culture, age, or region. Issues of identity, embodiment, performance, and objecthood are at the core of even the most conventional ventriloquist sketch: Where is the voice coming from? How is that voice split into many bodies? Whose voice is this? Who is speaking on behalf of whom? Using this popular form of entertainment as a structuring device for the exhibition allows for cross-collection discussions of the representation of sound and text, the traveling of the voice, and the misalignment between a voice and a body.

What sort of research did you do to develop your initial idea further?

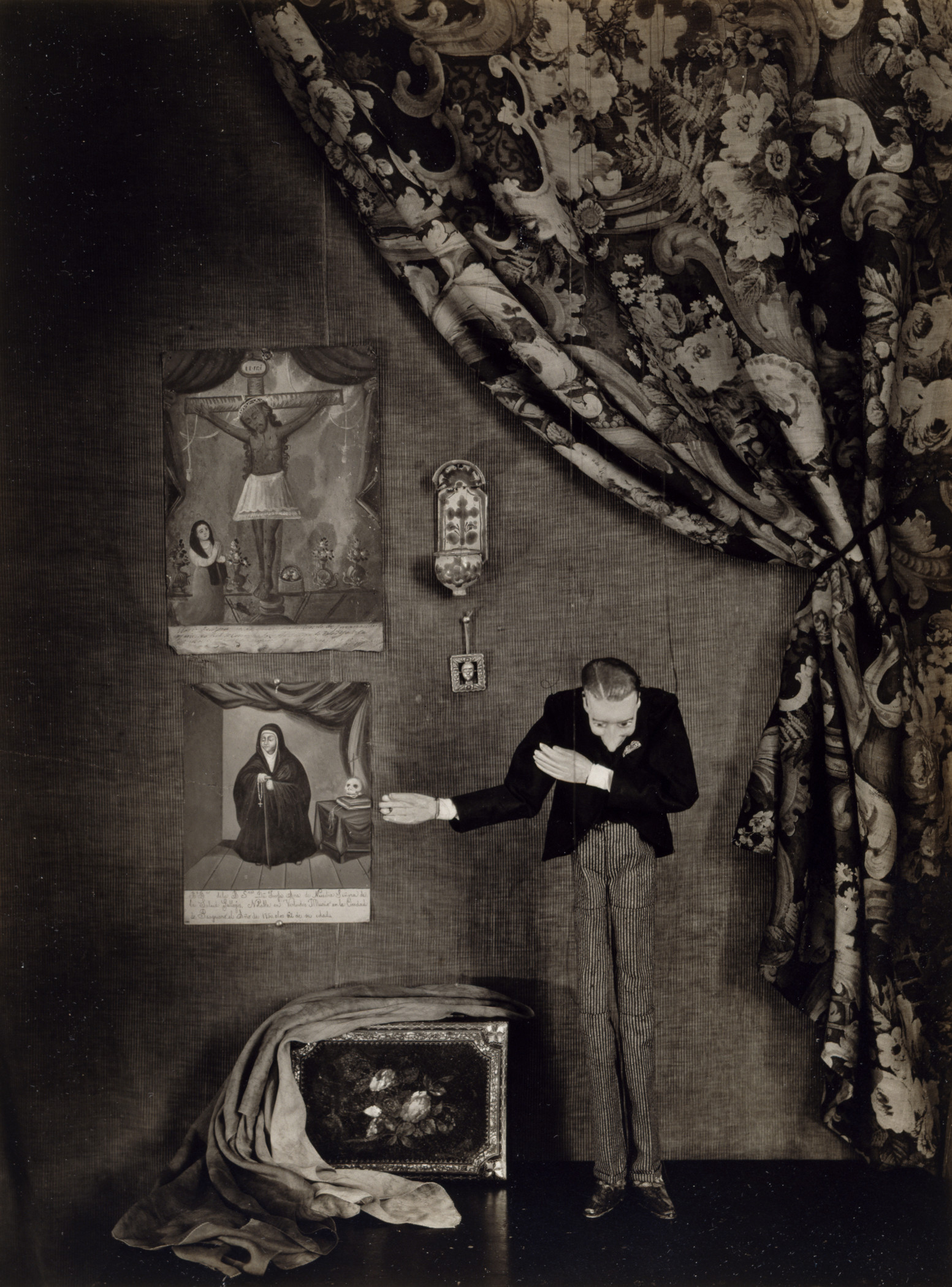

The more I worked on the exhibition, the more I realized this project was as much about the museum itself as it was about ventriloquism. To help us make that point, we borrowed an enigmatic photograph by Tina Modotti in which she portrayed her friend René d’Harnoncourt as a marionette taking a bow in front of several artworks. The scene is theatrical, reverential, and almost absurd. At the time Modotti made the photograph, 1929, d’Harnoncourt was an esteemed curator, researcher, and dealer in Mexico. Years later, he became an influential director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. An innovative eye towards exhibition design, as well as an appetite for the global, characterized his tenure. If one considers this fact, Modotti’s exquisite photograph gains yet another layer of meaning.

The research on the history of throwing voices led me to the incredible French ventriloquist Alexandre Vattemare, who later in his life became a philanthropist and an advocate for international cultural exchange. He played a decisive role in the foundation of the Boston Public Library, and is known as the father of the Inter-Library Loan System. I found this story revelatory, particularly if one keeps in mind the Modotti photograph, because it speaks loudly of the connections between ventriloquism and the dissemination of knowledge. In collaboration with the Los Angeles Public Library, NOT I features a work by Meriç Algün, The Library of Unborrowed Books, not only to honor Vattemare but also to point at the interrelation of museums, libraries, and disembodied voices.

Do the objects in the show include actual ventriloquist dummies?

The show includes one actual dummy, Elmer Sneezewood, made in the 1930s to work for/with ventriloquist Max Terhune. It also features a selection of artworks with puppets, dolls, and other surrogates. These ideas of art, life, and likeness traverse the exhibition.

How do the various objects in the show relate to—or dialogue with—each other?

To give you a specific example, Elmer Sneezewood will sit in a vitrine next to the Anatomical History on the Organs of Voice and Hearing by Julius Casserius (published in 1601) and Nancy Grossman’s sculpture No Name (1968) that consists of a leather mask with the lips sewn shut with a shoelace. These three objects represent different mechanisms for the production of voice and silence. Ventriloquism takes place even if there are no dummies in the equation. It can manifest in subtle ways. In his print Ven-triloquist II (1986), Jasper Johns speaks through quotations and references to his influences and inspirations, such as Barnett Newman or George Ohr. Like a ventriloquist throwing his voice through a dummy, the artist mobilizes an array of objects and images to create a temporary arrangement, a mini-exhibition almost, an argument to persuade us that an artwork contains many works within.

What guided or influenced the selection of objects from LACMA’s collections for the show?

Voice and hearing, but also sound and silence, guided most of the selection of the work, always paying attention to where the sound was coming from. I wanted to include artworks from as many LACMA collections as possible, to bring the strategies of the ventriloquist close to the “universal” profile of the museum, and the flawed ambition to represent all cultures, all ages, and all artistic manifestations of humankind. The subtitle of the exhibition, “Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE),” wants to be serious and humorous at the same time. It hints at an implausible time range that is hard to visualize in a museum gallery.

Tell us about the special projects and commissions made for the show and how they fit into it.

We invited three artists to produce new work for the exhibition. Raven Chacon created a sound installation with audio sourced from whistles in LACMA’s collection. Patricia Fernandez designed and carved frames for the six Francisco de Goya prints included in the show. Finally, Puppies Puppies (Jade Kuriki Olivo) created an installation that includes a dummy used for paramedical training along with a video on gendered robots, as well as the performance “Trans, Transfeminine, Femme, Trans Womxn, Trans Women, Gender Non-Conforming, Non-Binary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit people (Dedicated to Camila María Concepción—Rest In Peace)" that was videotaped in the galleries.

Is there a publication accompanying the exhibition?

The accompanying publication, Six Scripts for Not I, features five commissioned texts, written in the form of scripts for probable ventriloquist performances. Guest authors include art historian Darby English, poet Amy Gerstler, Professor of English Sarah Kessler, art critic and comedian Christina Catherine Martinez, and Film and TV writer Alan Page. The sixth ventriloquist script is the full checklist of the exhibition.

This article was first published in the Winter 2021 issue of Insider.