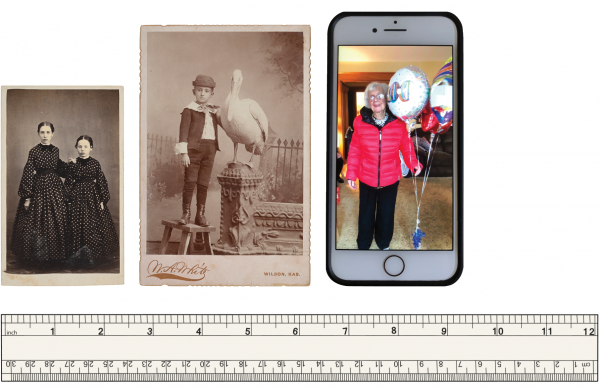

The term “cabinet card” is not very familiar today, but it was the most popular photographic portrait format in the United States at the end of the 19th century, from around 1880 through the release of the $1 Kodak Brownie camera in 1900. A cabinet card photograph measures 5 ¼ x 4 inches, mounted on a 6 ½ x 4 ¼-inch cardboard support—comparable in size and proportion to some popular smartphones. According to collector Robert E. Jackson, who gathered many of the objects featured in Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, 1870–1900, opening on August 8, 2021, cabinet cards have been “undervalued, underappreciated, and not well understood in terms of the visual richness and inventiveness that can be found there.” With this exhibition, we hope to spark a second craze for these delightful photographs.

![R. O. Helsom, [Card verso], 1880s, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson, P2019.74, photo courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art Ad for photographer](/sites/default/files/attachments/R. O. Helsom, Menomonie, WI, 1880s, relief print, Gift of Robert E. Jackson, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2019.74.jpg)

The cabinet card format was proposed in 1866 by the proprietor of a British photography studio, whose suggestion was picked up and promoted by Edward L. Wilson, the editor of a journal called The Philadelphia Photographer. Wilson’s motivation was economic, rather than artistic. The invention of photography in 1839 had sparked a great deal of excitement, leading to the establishment of studios in large cities and small towns across the country. These early studios offered small carte-de-visite portraits, approximately 4 x 2 inches in size, which were exchanged among friends and acquaintances. But customers still tended to visit photography studios only once or twice in a lifetime. Demand had to be stoked if these businesses were to survive, hence Wilson’s marketing campaign for a new, larger format.

![Alfred U. Palmquist and Peder T. Jurgens, St. Paul, MN, [Skater], 1880s, albumen silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2016.111, photo courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art Man in winter dress mimes skating on ice](/sites/default/files/attachments/EX8917_201-ACMAA.jpg)

Presumably the name refers to the fact that the cards could be displayed on the shelves of Victorian cabinets. In practice, they were also stored in albums, boxes, and drawers. To get a cabinet card portrait of oneself, one went to a professional photography studio, which was equipped with props, lighting, and in some cases, hair and makeup services. At their cheapest, a dozen cabinet cards could be purchased for $1.50, with notable urban studios charging as much as $6 per dozen. (By comparison, in 1880 a ladies’ bathing suit cost $9 and monthly rent for a four-room house in Camden, New Jersey, was $8. In today’s dollars, $1.50 is approximately $45.) While not exactly cheap, cabinet cards were within reach of middle-class, post-Civil War Americans who enjoyed increasing amounts of leisure time. As exposure times got quicker and photographers became adept at coaxing their customers into flattering poses, a visit to the photography studio could indeed be a fun experience, not simply a tiresome obligation. The examples in Acting Out are notable for their degree of playfulness and individuality. With their emphasis on performing for the camera, these exceptional cabinet cards mark a transition from the stiff, formal portraits of the preceding carte-de-visite era and the candid freedom and intimacy of the snapshots that followed.

![Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY, [Fanny Davenport], c. 1870, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2016.138, photo courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art Woman wearing 19th century dress resting head in hand by a decorated mantle](/sites/default/files/attachments/EX8917_009-ACMAA%20(1).jpg)

There is an undeniably “old-timey” aspect to cabinet cards, a time-capsule charm associated with their sepia tones, flamboyant typography, and Victorian fashions. Yet numerous parallels exist with today’s smartphone snapshots. Both types of photography were numerous, proliferating across many levels of society. Both encouraged individuals to demonstrate personality, humor, taste, and hobbies. Both have standardized measurements, can feature fanciful backdrops, or be refined by means of retouching or filters. Just as your phone snaps might be languishing in a digital cloud, actual cabinet cards could be tucked away in your attic or basement. Perhaps, inspired by Acting Out, you can bring them out for new generations to enjoy.

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, 1870–1900 opens on August 8, 2021. Member Previews are August 5–7, 2021. Purchase or reserve timed-entry tickets in advance.