This summer, LACMA launched the YouTube series ART + WORK, which shows the care that museum conservators put into preserving a wide range of artworks from our permanent collection.

In this video, I carefully sew sequins made from the wings of a beetle onto a 200-year-old textile from India. Below, I share how I found such unique sequins and the challenges of securing them to the textile.

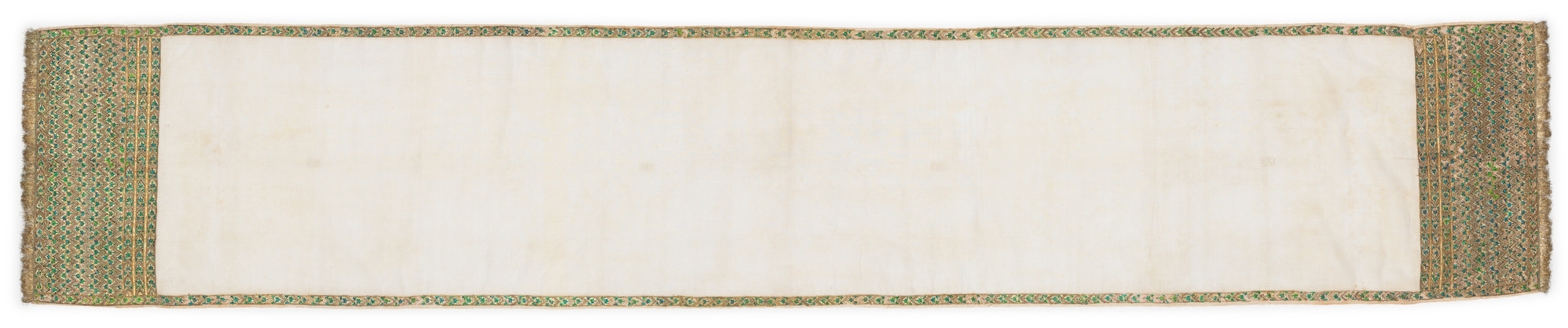

Fifty years ago, LACMA acquired this spectacular man’s sash, or patka, from the Heeramaneck Collection. Dating to the early 19th century and made in the Lucknow region of India, this length of fabric was embellished with the hard iridescent forewings, or elytra, of the jewel beetle (family Buprestidae). Though readily found in an area that ranges from India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines to Papua New Guinea, some jewel beetles are farmed today. The insects live and die naturally on the farms, after which their iridescent elytra can be sold for many uses, like making jewelry and other embellishments.

LACMA’s sash measures 132 ¼ × 24 ¾ inches (about 2 x 11 feet). A sash of this type would have been wrapped around a man’s waist with the decorative ends, or palla, hanging down in front.

Truly a luxury item, the beetle wing-covered sash is also embellished with gold- and silver-colored metallic-thread embroidery, black silk floss, and flat metallic-thread fringe.

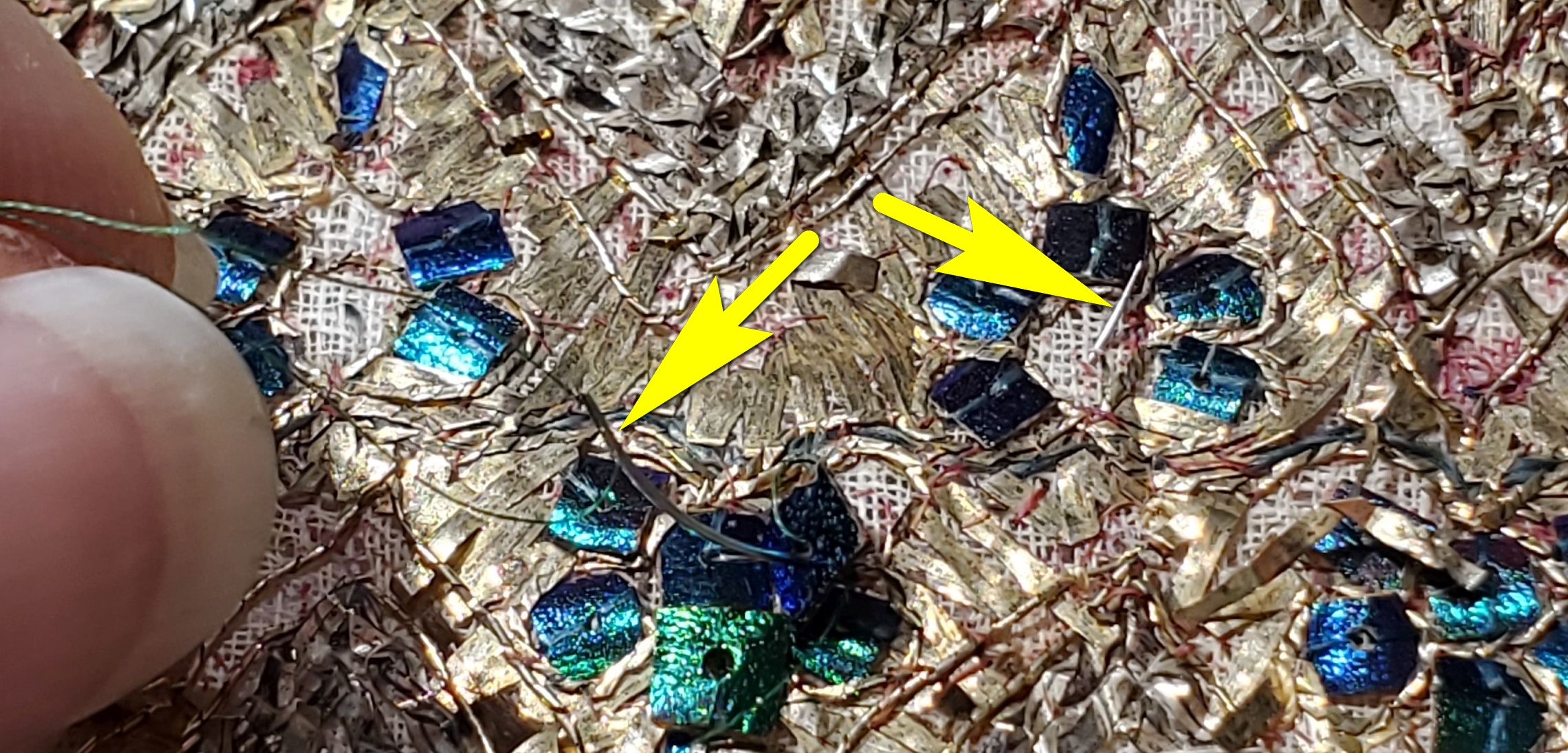

The textile had lost many original beetle wings, which were sewn down with a very fine silk thread to a lightweight plain-weave cotton fabric. The hard edges of the beetle wings were sharp enough to cut through the sewing threads until they broke, releasing the iridescent specks to the wind.

Curators in the Costume and Textiles department felt that the losses were distracting. If some of the larger losses could be filled, the viewer would be able to enjoy the piece as a whole. For me, this was an exciting challenge that I gladly accepted. Conservators, though, feel the pressure when a catalog photography deadline looms; with about two months to source beetle wings and to sew them in place, the clock was ticking.

After poring over several options, I selected ¼ inch (6 mm) round sequins punched from the elytra, green in color, with a hole drilled in the middle, thinking that precious time could be saved later on. The stitching hole I needed would be pre-drilled and trimming to shape could be done efficiently. I just had to wait four weeks for delivery from Thailand.

When the sequins arrived, I realized that the modern elytra were greener in color than the 200-year-old blue-green elytra on the sash. Perhaps I had purchased a different species.

Since this was the first time that I had sewn down such tiny sequins, each a little more than ⅛ inch (4 mm) across after snipping the edges of the round sequins into square shapes to match the originals, it was time to test and self-critique:

- The original sequins were more uniform in shape and size than I had thought.

- Each cluster contained square-ish sequins that fanned out, reminding me of a flower with petals. The replacements in these clusters needed to be snuggled closer together.

- The elongated slivers, such as the one on the left side of the area shown above, were the most difficult to imitate. Originally they had no hole and depended solely on two stitches to hold them in place. For longevity, I felt more confident stitching through a hole, but my copies were wide and clunky. With practice, I eventually mastered the original technique.

- My thread was too bright, so I switched to a duller gray-green thread.

- It became apparent that the green elytra would be a perfect color match with proper gallery lighting.

During the winter COVID-19 surge, with only 4 weeks to go and two heavily decorated ends plus 22 feet of side borders, I resolved to begin with filling the largest losses on the ends and then proceed to the side borders, jumping around so that the entire piece was always visually pleasing. If time ran out, the sash would look finished. Luckily, my sewing skills and speed improved, meeting the photography deadline for a beautiful exhibition catalogue for a future exhibition.

50 hours later, finished—for now!