In May, the Decorative Arts and Design Acquisitions Committee (DA²) held its 10th annual meeting. Working with the department’s curators, DA² helps LACMA add outstanding examples of decorative arts and design to our permanent collection. This year’s meeting was a huge success, with all of the objects approved for acquisition! Through the group’s generosity, we will add objects in many of our strategic collecting areas, including the Aesthetic movement, California design and craft, and international modern design. Also included are three contemporary pieces that will be in an upcoming exhibition that explores resonances between contemporary and historic works in clay from LACMA's permanent collection. This year’s meeting also supported the acquisition of several objects made by Black artists that represent design and craft traditions of Africa and the African diaspora. We are truly grateful to DA² for ensuring that all objects presented can be a part of LACMA’s collection, demonstrating important growth even in a year filled with such uncertainty and challenges.

This teapot is the most iconic design associated with the British Aesthetic movement of the 1870s and ’80s—a parody of its belief in pure beauty, or “Art for Art’s sake.” The figure who embodied the Aesthetic sensibility and its perceived excesses was the author Oscar Wilde, who famously said: “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china.” This aphorism is echoed on the bottom of the teapot, which reads: “Fearful Consequences Through the Laws of Natural Selection & Evolution of Living up to One’s Teapot”; the reference to the “Laws of Natural Selection” is explained by the teapot’s imagery and form. Except for the mustache, the male and female sides are almost interchangeable, and both display the tropes of the Aesthetic movement—sunflower, lily, muted colors, and floppy hat. The mincing gesture that forms the handle and the spout became the epitome of the camp pose.

Many in British society were afraid that a culture of aestheticism would lead to the blending of genders. Fear of the new Darwinian science was conflated here, too—as if the laws of natural selection would somehow lead to androgyny. No object could better and more amusingly embody satire about the affectation and decadence of the Aesthetic movement than this teapot.

After being forced to leave her native Cuba in 1935 because of her left-wing activism, Clara Porset became the most important designer as well as design advocate in 20th-century Mexico. Not only did she create furnishings for the country’s most renowned architects, but she was also very influential as a teacher, writer, and exhibition organizer on the subject of “objects made in Mexico,” promoting the integration of handcrafted, vernacular objects with industrial design.

Before the early 1950s Porset’s own furniture was handmade in small batches, so she herself could not address her goal of good design for all. Fortunately, one of Porset’s biggest fans was Antonio Ruiz Galindo, founder of Mexico’s two leading furniture companies. She started to design for his companies around this time and expanded her purview to mass production. With Porset being the voice of new Mexican design and Ruiz Galindo considered the country’s best furniture manufacturer, they were asked to produce all the poolside, beach, and garden furniture for the Hotel Pierre Marqués in Acapulco. This lounge chair is a stunning expression of Porset’s design philosophy. It has no decoration—the beauty of the piece depends on its excellent form, proportions, and materials, including mahogany as an indigenous wood and breathable cotton with braided cording to allow airflow.

Claire Falkenstein worked in scales from miniscule to monumental, producing astonishingly diverse work in sculpture, jewelry, painting, and printmaking. She began making jewelry in 1947 and continued for four decades. As she explained, “I treated jewelry as a means of teaching myself how to work metal. I could do little things, and have lots of failures, and it wouldn’t matter because they were just little things.” The brooch pictured at the top of this post represents what she called “wire delineations,” essentially drawing with wire similar to the way Abstract Expressionists painted without premeditation. For the necklace pendant pictured above, she was attracted to the way that heated glass gently oozes, melting a rounded mass of glass over the U-shaped copper and bronze construction. These two pieces have very personal provenance, coming from a dear friend and neighbor of the artist in Venice, California. They demonstrate two very different aspects of her work—manipulating metal and sculpting with metal and glass—and relate to her monumental metal sculptures.

Jomo Tariku’s Nyala chair reflects his artistic mission to translate African forms and motifs into contemporary designs. The chair’s back is inspired by the elegantly spiraling horns and graceful legs of the mountain nyala, an animal found exclusively in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia. The tripartite base is derived from simple three-legged stools with flaring legs familiar to Tariku from his childhood home in Ethiopia. The chair is made of bleached ash, which intensifies its message. The bleaching process renders the wood white and skeleton-like, resembling bone. Since the mountain nyala population has declined precipitously due to trophy hunting and habitat destruction, Tariku has used this design to raise awareness of their plight, limiting production to 1000, with each chair representing one living nyala.

The Chicago designer Norman Teague strives to reshape the design canon through his practice, drawing on histories of Black design, craft, and culture. His work is deeply rooted in community, emphasizing common, locally sourced building materials and Chicago fabricators as well as mentorship and economic development. The Sinmi stool began as an exploration of the notion of “venting” and “chilling.” Teague developed a form that accommodated a range of informal postures, such as perching and leaning, and named his stool “Sinmi,” which means “to relax” in Yoruba. Teague’s 2020 Africana line reinterprets Western furniture forms through the lens of West African ritual and culture. The carved rail of the rocking chair evokes face painting and scarring practices, while the chair’s broad proportions reference handcrafted African stools.

.jpg)

Oakland-based ceramic sculptor and painter Woody De Othello uses cartoonish forms and anthropomorphic whimsy to convey thoughtful meditations on the experience of Black American life and culture. In Blank Faced, the artist explores the face jug tradition associated with mid-19th-century African American craftsmen (both enslaved and free) in the Edgefield district of South Carolina. Many scholars believe that the vessels reflect the continuation of African religious and spiritual practices. For Othello, who is of Haitian descent, the jugs represent the complexity of the African diaspora. Regarding the merger of human and object in his work, the artist noted he is “captivated by this idea of the vessel being an analogy of the human body and a carrier of emotions.”

In the late 1960s, Dale Brockman Davis was an undergraduate studying ceramic arts at the University of Southern California. While Davis had begun to lose interest in the subject, he recognized that the status of his draft deferment depended on his academic performance. Viet Nam War Games (1969) powerfully captures his staunch opposition to the war as well as the shadow it cast over his artistic pursuits. Davis reframed his thrown ceramic vessels into large missile-like forms, smearing one with blood red paint. His inclusion of found metal elements into the sculpture signaled his growing interest in assemblage, a shift that was deeply influenced by his involvement in the Black Arts Movement. By this time, the young artist had already co-founded the now-legendary Brockman Gallery, a Leimert Park institution that provided opportunities for Black artists at a time when they were largely neglected by the Los Angeles art establishment.

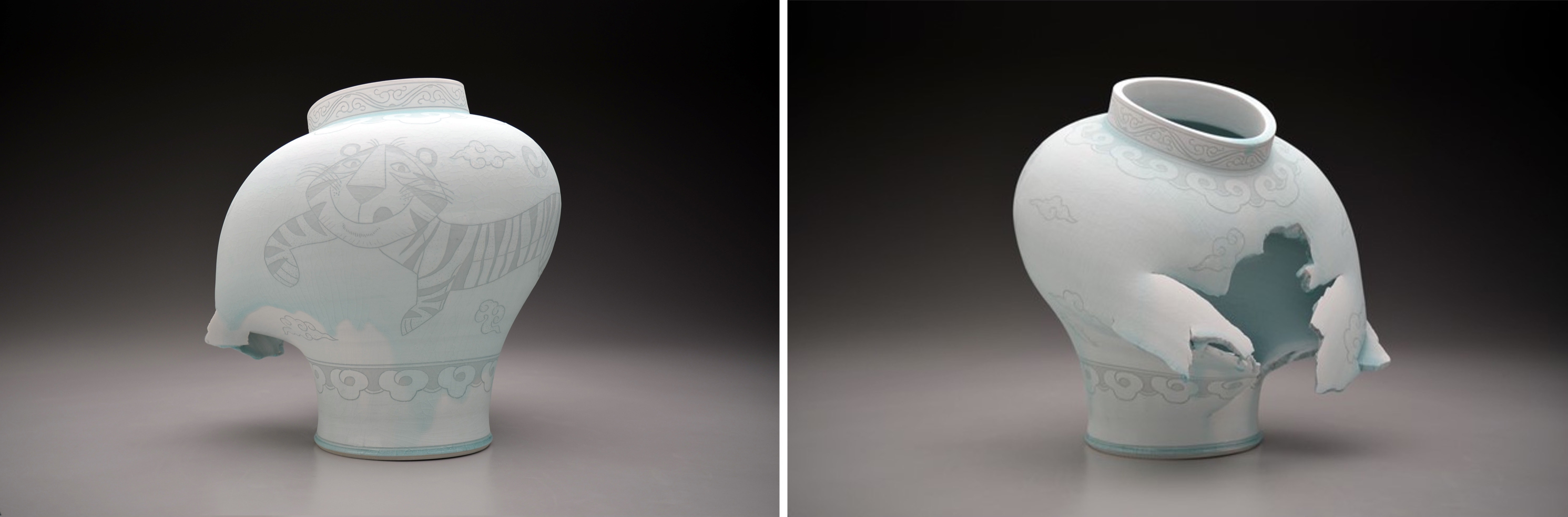

The Chicago-born son of Korean immigrants, Steven Young Lee is resident artistic director of the internationally recognized Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Helena, Montana, and has taught and lectured widely across North America and Asia. Lee explores the consequences of intentionally damaging his vessels prior to firing them in the kiln as a critique of the perfection of manufactured porcelain wares. In Jar with Tiger and Clouds, he also addresses his experiences as an outsider in his parents’ native country as well as one of a minority of Asians in the state where he now lives by playfully integrating his Korean and American heritage. Directly inspired by Korean ceramics from the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), Lee has updated the auspicious animals that traditionally adorn this type of vessel by instead depicting the original 1950s version of Tony the Tiger (mascot of the American breakfast cereal Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes).

Los Angeles–based Filipino American artist Elyse Pignolet redefines the misogynistic term “trophy wife” in this candid piece modeled on historic ceramic forms. Adorned with the names of prominent women romantically involved with powerful men, Trophy Wife calls out the divisiveness of this disparaging stereotype, and invites the viewer to recognize how each woman portrayed has confronted it. The historic forms referenced by this work resonate with its subject. The proliferating pairs of handles evoke the handles of elaborate vessels that became a defining feature of modern-day trophies. Large-scale blue and white earthenware vessels such as this were first made fashionable by Queen Mary II (1662–1694), who co-ruled Britain with her Dutch husband William. Pignolet’s celebration of women denigrated for their relationships with men is amplified by the work’s allusions to prototypical trophies and female patronage.

Julia Kunin is the one of the first foreign artists to have gained access to Hungary’s historic Zsolnay ceramics manufactory, which was internationally recognized in the 1890s for its radiant “eosin” metallic lustered glazes (named after Greek goddess of the dawn, Eos). This glaze is proprietary to Zsolnay and remains a secret recipe. Inspired by the luminous works she saw illustrated in the Bard Graduate Center’s 2002 exhibition on Zsolnay, Kunin began working with the factory in 2009. By studying the Hungarian language, she communicated directly with Zsolnay’s glaze chemist to achieve the experimental effects of Indigo Garden. The work’s shape is informed by ceramics adorned with casts of local pond life first produced by French Renaissance polymath Bernard Palissy (1509–1590). However, the casts of hermaphroditic snails (each simultaneously male and female, but requiring another snail to reproduce) are a recurrent motif in Kunin’s work that she associates with her own lesbian identity.