Sabrina Gschwandtner is a Los Angeles-based artist who works at the intersection of new media and traditional craft. Her video Screen Credit is currently playing on the monitors above LACMA’s Stark Bar through March 15, 2022, and will resume on June 21, 2022, following the upcoming exhibition Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Decorative Arts and Design curator Bobbye Tigerman spoke with Gschwandtner about how she developed this body of work.

Bobbye Tigerman: Sabrina, you are well known for creating “film quilts,” in which strips of film are sewn together in patterns derived from historical American quilts. How did you get started making this work?

Sabrina Gschwandtner: In 2009, I received a box of 16 mm films that were deaccessioned from the Fashion Institute of Technology and given to me by the Archivist of Anthology Film Archives. I watched all of the films and felt sad that the movies’ subject matter had been deemed unworthy of archiving. The films were short textile documentaries, dated between 1950 and 1980, that examined textiles and portrayed the women who made them. Some of the film had faded, adding an additional layer of valuelessness. I wanted to recast these undervalued histories of women’s handcraft work, and celebrate the fading medium of film, so I started making “film quilts” out of the material by cutting and sewing lengths of film together.

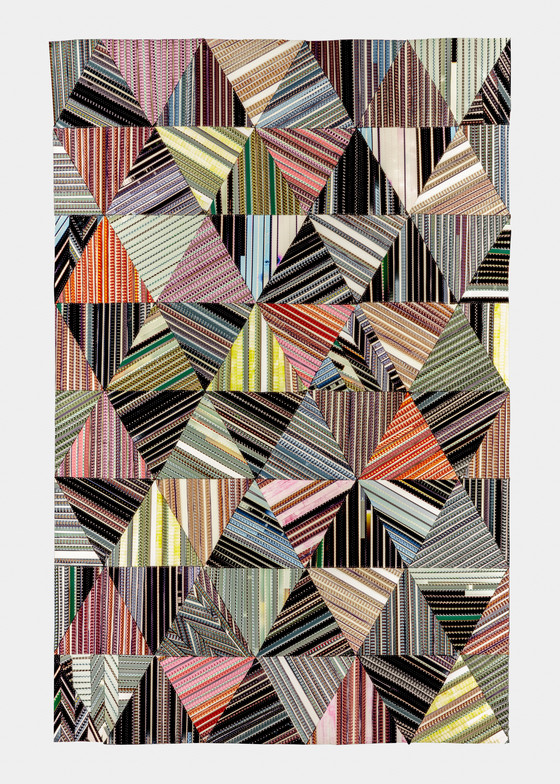

Bobbye: What were the original sources that you used for Hands at Work Film? What were you trying to achieve with the triangular composition and the juxtaposition of different film sources?

Sabrina: The piece uses footage from about a dozen different films in my collection, including some films that I made, like my college thesis film from 1999. All of the footage I used shows hands working on various projects or tasks, like quilting, dyeing, weaving, sewing, spinning, operating machinery, voting, excavating, gardening, and making shadow puppets. Triangle quilt patterns are often made out of scraps, and I think of the triangles in this piece as records not only of my labor and of the handcraft history of film editing, but also of the tactile quality of film, as it wanes in use.

Sabrina Gschwandtner, Hands at Work Video, 2017, © Sabrina Gschwandtner, courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Bobbye: Hands at Work Video is an extension of Hands at Work Film. Can you talk about why you chose to work in a digital format and how you translated your ideas and imagery?

Sabrina: Making film quilts is three-dimensional film editing. In some ways, I act very similarly to a film editor—after I decide on a quilt pattern, I choose scenes and I hang those strips of film onto a trim bin, just like a film editor would. Then I start working like a quilter, and I sew those scenes together into a kind of fabric, then I cut that fabric into shapes, and then I sew those shapes together, thinking about how the shapes fit together into an overall narrative. I consider color, rhythm, and timing, just like a film editor would. I wanted to translate the parts of that process that more closely align with quilting to video editing.

So I edited Hands at Work Video like it was a digital patchwork quilt: first I created an overall pattern design, then I made each triangle of video one at a time, and then I put the video triangles together into sequences, thinking about content, color, rhythm, shape, and positive/negative space. For the triangles containing film footage, I chose clips of women’s hands at work on a textile project. As I was making it, I was thinking about the tactile pleasure of working with fabric, about the labor that goes into making textiles, and how undervalued this labor is.

Sabrina Gschwandtner, Screen Credit, 2020, © Sabrina Gschwandtner, courtesy the artist and LACMA

Bobbye: What was your impetus to make Screen Credit? How did it emerge from the Hands at Work pieces?

Sabrina: There’s a section of Hands at Work Video where I placed triangles of hands knitting next to credits from Pat Ferrero’s film Hearts and Hands, and to me it looked like the hands were knitting (creating) the text. Too many women artisans have gone uncredited. Too many women working in film have gone uncredited. Screen Credit explores both. (“Screen credit” is a term that refers to film credits that acknowledge the work of both on-screen and behind-the-scenes talent).

Bobbye: The editing of Screen Credit is particularly complex. Can you talk about the structure of the piece and your editing process?

Sabrina: Editing this piece was arduous because there were so many different pieces to keep track of. There are 24 different triangles where video can go, and I wanted to explore as many different pattern combinations as I could. I used footage from three different films: Lotte Reiniger's 1922 Cinderella, and Pat Ferrero's 1981 Quilts in Women's Lives and her 1987 Hearts and Hands.

I knew the piece would loop because of how video is shown at Stark Bar, so I edited it to have a circular progression—from layers of film credits to layers of cutting and sewing footage to a playful sequence of different quilts being pieced together, and then back to credits, but this time alongside hands sewing and working with fabric squares.

The video connects film editing to quilt-making, and I hope that because the two artistic forms are so intertwined, I challenge how the classifications of quilter and artist have been segregated from one another by art history. Merging these different forms of artistry in the same space is a reparative act.

Bobbye: What direction did your work take after you completed this series of pieces?

Sabrina: I continued repairing history. I was very privileged to study film at esteemed institutions—Harvard, Brown, Bard—and I never learned about the women who made movies in the silent film era. Their work has been excluded from the male-dominated history of film.

I’m so grateful to the Women Film Pioneers Project for providing an incredible resource for women’s global involvement in film production during the silent film era.

I’ve been sourcing films made by women pioneers from archives as video files, printing them onto black and white 35 mm film stock, and then cutting and sewing the footage into quilts. So much of this pioneering work wasn’t ever saved and archived—especially films made by marginalized women—so I’m also making artwork about women whose films were lost, by writing about their work and embroidering their names onto blank film.

Screen Credit will be on view at Stark Bar through March 15, 2022, and again from June 21, 2022. Gschwandtner’s solo show Scarce Material, about women cinema pioneers from the silent film era, is on view at Shoshana Wayne Gallery from March 12–April 16, 2022.