James R. “Jimmy” Hedges III was an artist and philanthropist who advocated for self-taught artists and ran the Rising Fawn Folk Art Gallery, in Lookout Mountain, Georgia, which was active from the early 1980s until his death in 2014. LACMA has a longstanding tradition of showcasing folk and vernacular art that spans the museum’s history: Folk Sculpture USA (1976), Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art (1992), and Outliers and American Vanguard Art (2018) are just a few noteworthy exhibitions, and gifts by Gordon Bailey of significant work by Purvis Young and Lonnie Holley began to seed a growing area of interest shared by the American Art and Contemporary Art departments. Meanwhile, artists like Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, David Hammons, and others exhibited at the museum have paid homage to folk, vernacular, and outlier artistic expression.

I had an opportunity to talk to Jimmy's son, Jim Hedges, about his father's legacy and recent generous gift to LACMA.

First off, I would like to ask you about the family legacy and passion for supporting artists. Can you talk a bit about how your father got interested in not just collecting but advocating for artists?

My father, Jimmy Hedges, was an artist himself, a self-taught wood carver and sculptor. In the course of learning more about his craft, he became friends with other self-taught artists in the South, and that grew his love for Southern folklore and, notably, African American self-taught art, which tends to focus on religious themes, daily work life, and social justice. As head of our family’s charitable foundation, my father was also able to provide economic support to working artists and helped elevate their standing by helping them acquire supplies and placing their work in major collections and arts institutions around the U.S.

Related to that, can you talk about the long-term and personal relationships that your father developed with artists?

Many of these “outsider” artists became my father’s closest friends, confidants, and teachers. He was a student of their practices, their life lessons, and their social standing. He became especially close to a few of the most noteworthy outsider artists of his era, notably Purvis Young, Lonnie Holley, Bessie Harvey, and the Gee’s Bend quilting families.

I'm also curious about how your father felt about the institutionalization of “outsider art”? I suppose he was interested in the mainstream changing its ways of codifying or separating vernacular and so-called schooled or fine art.

My father always served as a bridge between the artists and private collectors, curators, and institutions. As he had a foot in both worlds and the ability to provide financial support to help the artists, he was integrally involved in helping them gain increased financial security and representation in the traditional art world.

Like your father, you too have a personal and passionate connection to collecting that represents your myriad interests. Did it take you a while to refine what you wanted to collect?

Absolutely. I began, like many young collectors, chasing down various interests but, in time, my tastes began to focus, largely thanks to my participation on the board of the Dia Art Foundation, with its conceptual and minimal artist roster.

Can you share a bit about what is included in the Jimmy Hedges Papers on Outsider Art that are housed at the Archive of American Art at the Smithsonian? If you had to pick something from that archival collection that best captures your father's spirit what would it be?

When my father passed, I visited his home on his farm in Northern Georgia and was looking through his library books. On the shelves, I found scores of three-ring binders with notations, like “Alabama, 1987.” My father had categorized all his visits to artists’ homes, recording with photos and video films, hand-written notes, directions, recipes, and even small artworks. I knew immediately that he had created a treasure trove of research materials that not only described his literal and figurative journey but also could provide immeasurable support to students and curators researching the outsider art world.

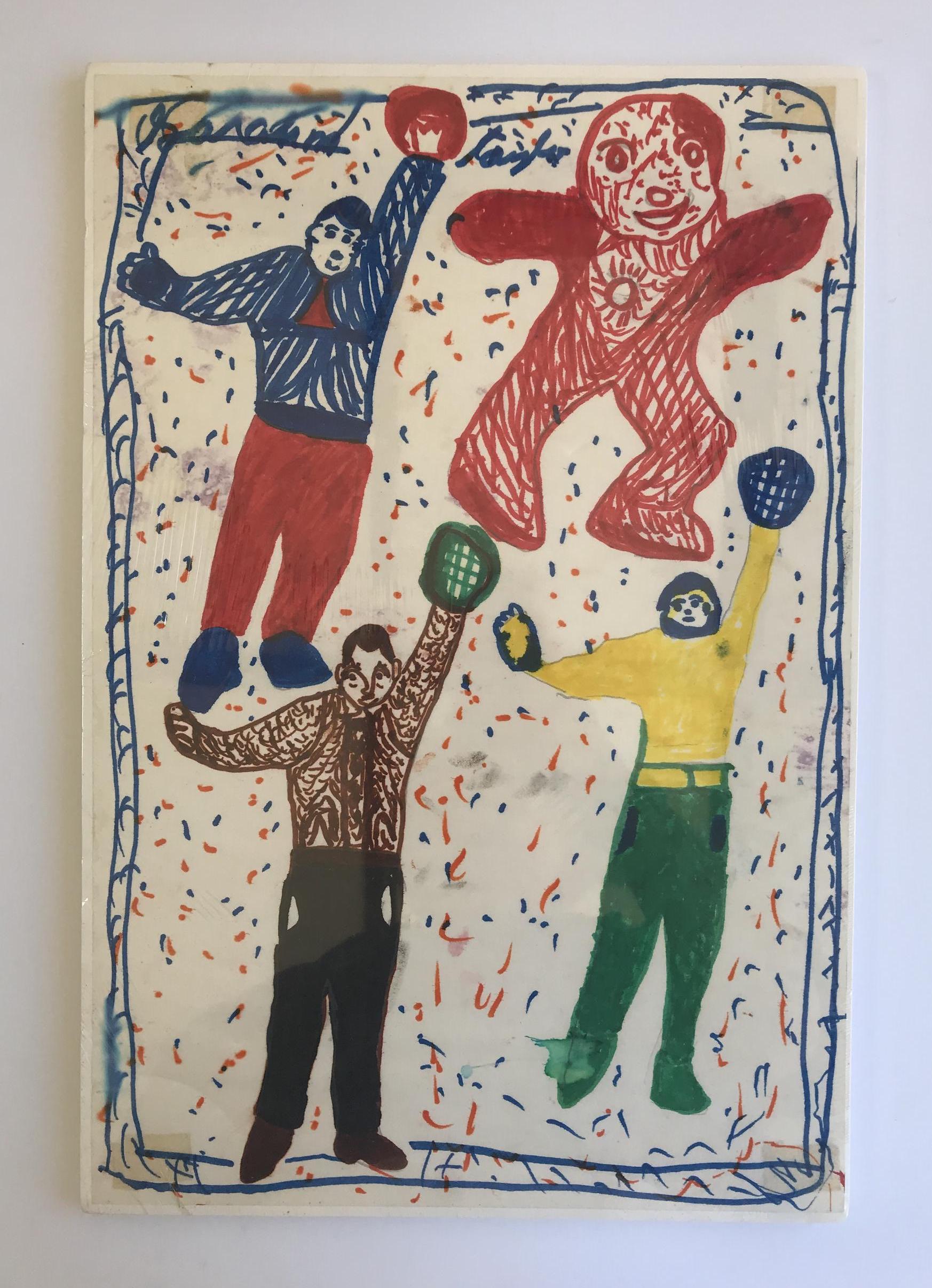

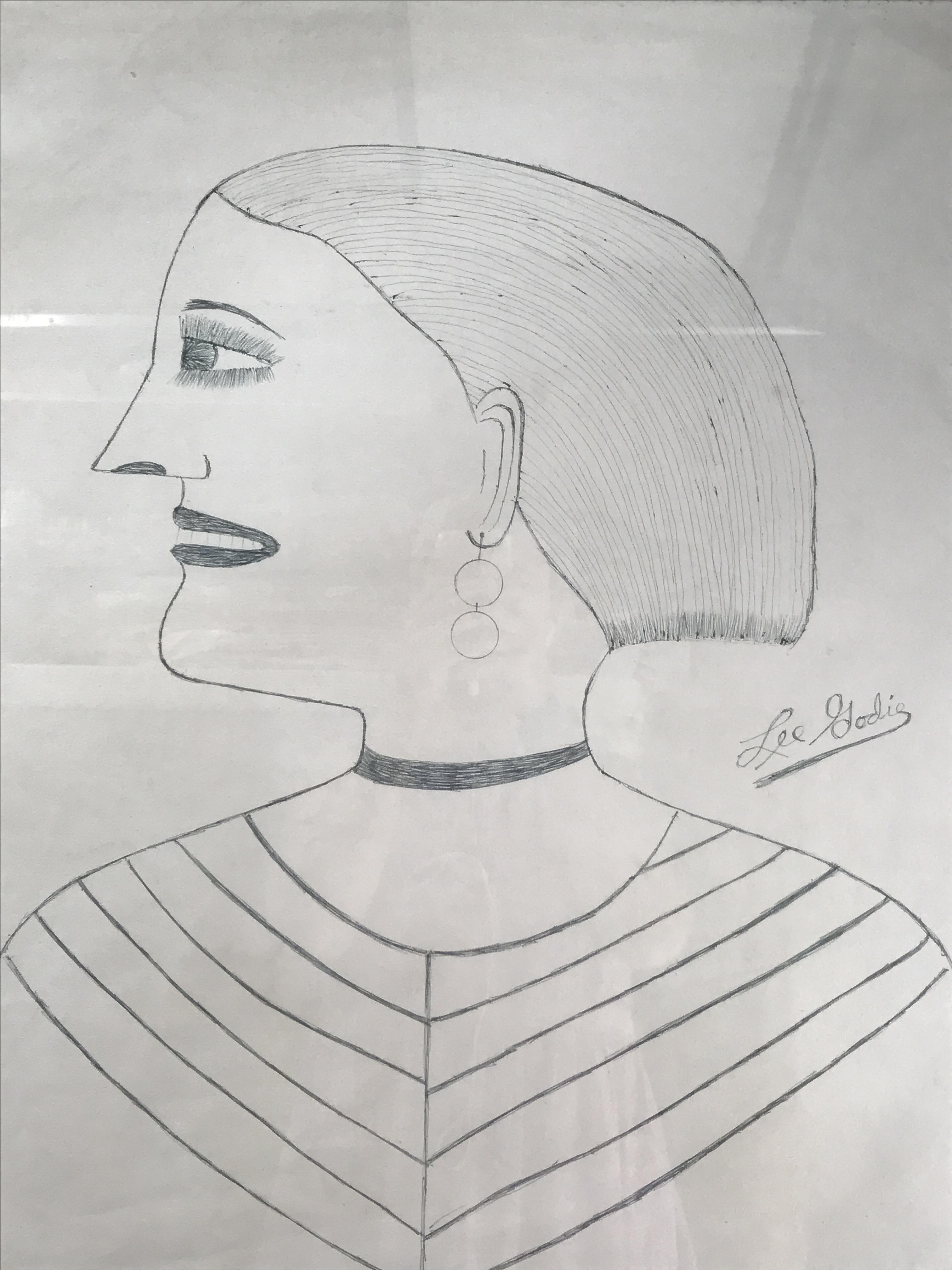

One of my father’s great legacies was a cookbook called Panky’s Pantry Secrets. He believed that cooking too was a fine art, and an often self-taught art. He created a legacy of one woman’s journey as a cook with illustrations from all sorts of Southern self-taught artists. One one page, there is a recipe for cheese grits or boiled custard, or Hoppin' John, and on the opposite page, one might find an illustration of a great work by Purvis Young, or a Gee's Bend quilt or even an Edmundson grave marker.