On the evening of August 13, 1521, just over a year after the controversial death of Moctezuma II (Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin), Cuauhtemoc (Quauhtemoctzin), the young—and final—ruler of the Aztec Empire, made his way down the canals of war-torn Mexico-Tenochtitlan to negotiate peace with the invading Spaniards. Decades later, as an epidemic (huey cocoliztli) ravaged what had been rechristened as Mexico City, the capital of New Spain, Nahua historians committed to an ambitious world-sustaining project of their own: recording their knowledge and histories in an illustrated encyclopedia known as the Florentine Codex. Their account of the war (Book 12) begins with an omen, which appeared ten years before the Spanish arrived. A pyramid of fire, a banner of clouds, piercing the very heart of the sky. A new axis around which a new era would be oriented. Mixpantli.

500 years later, as the world emerges from another devastating pandemic, Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico contemplates the legacy of the works produced by Indigenous knowledge-keepers (tlamatinime) and artist-scribes (tlacuiloque) living under Spanish rule. Theirs is a story of creative resistance and resilience, of adaptation and negotiation, of making the world anew. Wielding the generative, creative power of artistic practice, these tlacuiloque defined a new era, reorienting space and time through novel works of art—illustrated histories, featherworks, stone sculptures, cartographic paintings—all which situate European Christendom within Indigenous cosmovision. Mixpantli is a symbol of the monumental clash of these two worlds, and the deftness with which Nahua artists imagined a dynamic and multifaceted future by becoming fluent in the cultural traditions of both.

ESPAÑOL

La noche del 13 de agosto de 1521, algo más de un año después de la controvertida muerte de Moctezuma II (Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin), Cuauhtémoc (Quauhtemoctzin), el joven y último gobernante del Imperio Azteca, navegó por los canales de México-Tenochtitlan, que había sido devastado por la guerra, para ir a negociar la paz con los invasores españoles. Décadas más tarde, mientras una epidemia (huey cocoliztli) asolaba la que había sido rebautizada como Ciudad de México, capital de la Nueva España, un grupo de historiadores nahuas estaban dedicados a completar un un ambicioso proyecto para preservar su mundo: registrar sus conocimientos e historias en una enciclopedia ilustrada conocida como el Códice Florentino. Su relato de la guerra de conquista (Libro 12) comienza con un presagio: una pirámide de fuego, un estandarte de nubes, que perforan el corazón del cielo apareció diez años antes de la llegada de los españoles. Este presagio era la imagen de un nuevo eje cósmico alrededor del cual se orientaría una nueva era; lo llamaron Mixpantli.

Quinientos años después, mientras el mundo emerge de otra pandemia devastadora, Mixpantli: Espacio, tiempo y los orígenes indígenas de México contempla el legado de las obras producidas por los guardianes del conocimiento indígena (tlamatinime) y los artistas-escritores (tlacuiloque) que vivían bajo el dominio español. La suya es una historia de resiliencia creativa, de adaptación y negociación, y de poder hacer el mundo de nuevo. Ejerciendo el poder generativo de la práctica artística, estos tlacuiloque definieron una nueva era, reorientando el espacio y el tiempo a través de novedosas obras de arte (historias ilustradas, trabajos en pluma, esculturas en piedra y pinturas cartográficas), todas las cuales sitúan a la cristiandad europea dentro de la cosmovisión indígena. Mixpantli es un símbolo del choque monumental de estos dos mundos, y de la destreza con la que los artistas nahuas imaginaron un futuro dinámico y multifacético conformado por las tradiciones culturales de ambos mundos.

NAHUATL

In Yohualpan 13 chikueyi metstli itech 1521, niman se xihuitl satepan ipanon yolkokolistli okimiktiaya Moktezuma II (Motekuhsoma Xokoyotsin), Kuauhtemok (Kuauhtemotsin), in telpokatsin ihuan tlamikeh tlayekanki tlanahuatilaztekatl, oanehnemi ipan atoyameh itech Mexihko Tenochtitlan, okinmakakeh yehika hueyi kaxtilanyaoyotl, ahmo okinhuelikeh otenonotzayaya kaxtilankoyomeh. Xihuimeh satepan, niman hueyi kokolistli ohuetzikeh ipan okitokayotiaya hueyi altepetl Mexihko, iyoloaltepetsin yankuik kaxtilnantlalpan, tesepantilli tlamatinimeh okintekitikeh huilihki yehika ahmo polihuis iyuhkatilis: okinkuilohkeh itlamatilis ihuan inemilis ipan hueyi amatlatsontli okitokayotiaya Florentinoamoxtli. Itlapohualis kaxtilanyaoyotl (Amoxtli 12) omopeuh ika se tetsahuitl; sente tletlatsakuali, niman mixpantli, ilhuikayolminayotl okinextiyaya maktlahtli xihuitl achto okimhualakeh kaxtilantlakameh. Inin tetsahuitl ixayauh in yankuik kuauhilhuikapan monechikohua monextia se yankuik kahuipan; okitokayotiaya Mixpantli.

Satepan sentsonmakuilpoali xihuimeh, niman tositsimitsin mokisa oksepa ipanon hueyi kokolistli, Mixpantli: Yeyantli, Kahuitl ihuan toachtomasehualtsitsin Mexihko kimopilia in yuhkatilistli okimchiuhkeh tlamatinimeh ihuan toltekameh ihuan tlahkuilohkeh ahkihuan okimnemiliaya kaxtilankopa. Ipanin ihtolokan okachi kualli, nosepanian tenonotsalistli ihuan mohuelis mochihuas oksepa yankuik tsitsimitl. Tlayehyekolistli huelitini monextia tlachihualistli, inintin tlahkuilohkeh temachtia yankuik kahuipan, tlatlamelauhkatiuh in yeyantli ihuan kahuitl yehika mahuistlamankayotl (tlaixpankopinalli, tlahkuilolistli, tlatetikalistli ihuan tlalkopinali), ipanin nochin kateh kixtiancoyotlan ihtih tomasehualnemilis. Mixpantli in machiotl itech momakakan ipanon omextin yuhkatilistli, ihuan iyektilis okimchiuhkeh toltekameh kenin tlaltemikeh mostlayotl olinia tesepantilis ika omextin nemilistli.

ZAPOTEC

Lle’ shnhej, bio’ xonho’, iz 1521, yelhate’ ndé twiz katen got Moctezuma II (Motecuhzoma Bzeb) Cuauhtémoc (Quautemoctzin), to bene’ xkuide’ zelhao gwnhabia’Yell xhen Azteca, le’ gwyoe’ gwze’ lo’ lhatj nhis che Sita’-Tenochtitlán, yell nhi benhitten nhak da’ yelagwdilen gok, lhen bene’ ljelle’ zeje’ weshalj lhen benextilha’ ench koez yelagwdila’. Zan shi koen iz bach gwde, katen gwchhe’ to yillwe’ walh (huey cocoliztli) bososhe’ lhe lhatjen nha’ gosenhen Ciudad de México, lhatj walh che Nueva España, zan bene’ sinha’ nahuas sjayo’ lo’ nha’ yososalhawe’ to llin walh da’ gwllon dan ba chhesak Yellhion: gosonhe’ wezoj da’ ba chhesake’ nha’ dilla’ ka gok che’ lo’ to yishwelhab xhen da’ nchhente, da’ nzi’ Códice Florentino. Dan chhoe’ dilla’ nhaken gok gwdil che Conquisten (Yiswelhab 12) tsolaon lhen to dilla’ chkuia lhao: to yo’o gwlhas yi’, to lhachhe’ bejw, nha’ da’ seyidjw lhalldao Yelllhio blhan kate’ za’ gak shi iz yeselha’k benextilhe ka’. Dilla’ chkuia lhalle’ nhi nsa’n to da’ kob chhechj Yaba da’ shlhoen gak nllalhe: len na’ bosozoe lha Mixpantli.

Bagok gayogayoa iz na’, nha’ na’ chshaglhaochho Yelllhion yeto yillwe’ walh, Mixpantli: Lhatj ka nha’ nha nhak gok gwxhe Yell xhon Sita’ shlhoen chhio’ na’, katgen goson benen gosap shie’ dan gosak benexhon ka’ (tlamatinime) nha’ bene’ wezoj (tlacuiloque) gosenhabia’ benextilh ka’ le’. Da’ walhen gosonhe’ gosonhe’ ka’, goseyilhjw lhalle’ nhaken gosonhe’ weshalj , ench yeyak shawe’ che Yelllhion. Goson yane’ ka zelhao chhesake’ yelawezoja’, bene’ tlacuiloqui kí, bosoxie’ to da’yoblhte, bososhe’ lhatjen lhen kan gok nha’ bosoxie’ da’ nlla’telhe (bosochhenhe’ kan gok, llin dobe’, gosonhe’ da’ gosonhe’ lhen yej nha’ bsochhenhe’ yishwelhab), yogo’ da’ ki shlhoen ka chjanhi’lhalle’ Cristo yell lhalle’ nha’ bosoden lo’ xbab che benexhon. Mixpantli nhaken to da’ shlhoe’ nhaken bosotil ljell chop koen Yellhio bene’, nha’ dan chhesak yane’ benexhon nahuas ben lhatj gwyalhjo to nhez kob da’ gwlhoen kayanen gok, to da’ nchixe chop koen kan chhososa’ lhalle’ chop yell nllá’.

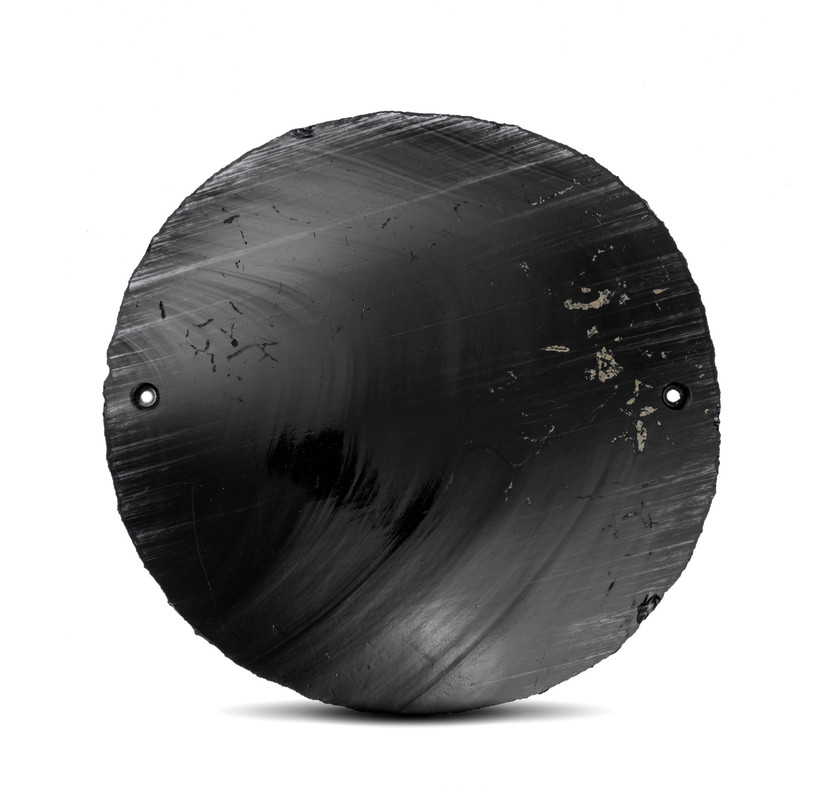

Obsidian Mirror, 1325–1521

Divine rulers and ritual specialists in Mesoamerica have long used mirrors, crafted from stoney materials like pyrite and obsidian, to foresee what the forces that govern the cosmos hold in store. Mirrors allow for special sight, beyond the limited vision of humankind. In Book 12 of the Florentine Codex, authors describe the seventh omen of the Spanish invasion as the appearance of a crane with a round mirror in the middle of its head. When Moctezuma gazed into its dark surface, he saw the starry sky that hangs over the world-renewing New Fire ceremony, and then an armed horde arriving on horseback.

Espejo, 1325–1521

Los gobernantes divinos y los especialistas en rituales de Mesoamérica han utilizado espejos, elaborados con materiales pétreos como la pirita y la obsidiana desde hace mucho tiempo para prever lo que las fuerzas que gobiernan el cosmos tienen previsto. Los espejos permiten una visión especial que va más allá de la limitada visión del ser humano. En el Libro 12 del Códice Florentino, los autores describen el séptimo presagio de la invasión española como la aparición de una grulla con un espejo redondo en medio de la cabeza. Al mirar su oscura superficie, Moctezuma vio el cielo estrellado sobre la ceremonia del Fuego Nuevo, que renueva el mundo, y luego una horda armada que llegaba a caballo.

Teskatl, 1325–1521

In teotlayekankeh ihuan tlamatinimeh hueyi Nepantlali mopalehuiaya in teskatl, motechihua ika teotetsin ihuan teoxalchihuitl yese miek xihuitl pampa in tlamatinimeh kipohuah in tonalamatl ihuan nochi ilhuikayotl kilhuia. In teskatl kipalehui mokihta in teotlamantin ihuan nochi ahmo kahsikamati in tlakayotl. In Florentino Amoxtli matlakome, tlahkuilotinimeh kihtohuah inik chikome tetsahuitl ahkualhualahkeh kaxtiltlakatl monesi in kecholi ika yahualtiteskatl ipan kuatsala. Ipan in yohualteskatl, Moktesuma kita in sisitlalilhuikatl ipan ilhuitl yankuik xiuhmolpilli, kipatla in semanahuak, satepan huala in yaotekatl onhuala in hueyi masatl.

Yej gwba’o, 1325–1521

Bene’ bda’o gwnhabia’ nha’ benexban wen lni bda’o che Yellxhon walh bosochinhe’ gwba’o da’ gosonhe’ lhen yej gwlhas, nha’ yej gwba’o, kanhíté, ench blho’en yelawalh gwnhabia’ nsa’ Yaba. Kanhak yejgwba’on, chho’en lhatj nho shlhe’ da’ nllalhetelhe ka da’ shlhe’ lhao benach. Lo’ yish welhab shilline (12), da’ da’ lo’ Yishwelhab golh Florentino, lo’ dilla’ gwkuialhao gall nhan sjanzoj wezoj ka’ nhakyanen gok bewselha’k benextilh ka’, katen beselhede’ to bellia xilhe da’ to yej gwba’o lo’ xgaba’. Kate’ blhe’ Moctezuman ka gasj ba’o nhakba’, nhachh gwkos yichjen gwne’ Yaban lliachgoan beljw, zejten tolí gan chhak lni Yi’ Kob, yi’ da’ chhokob Yelllhio, nha’ lez ka’kse blhede’ toshonj bene’ weka’ ya sjallia Kabayw.

Sculpture of Xiuhtecuhtli, 1250–1521

Xiuhtecuhtli, or “Turquoise Lord,” a youthful lord of fire, imbued Mexica rulers with the power—and responsibility—to propel time forward. The Nahuatl word xihuitl means “turquoise” but also “year,” connecting the deity with the solar cycle. Festivals dedicated to Xiuhtecuhtli both commemorated and protected this cycle. Every four years, at the festival of Xiuhtecuhtli in Tenochtitlan, the Mexica ruler would dress in the guise of the deity and dance, embodying his divine power. Xiuhtecuhtli also governed the essential New Fire or Binding of the Years ceremony, a rite enacted every 52 years to maintain the sun’s cyclical journey and, thus, the solar era.

Xiuhtecuhtli, 1250–1521

Xiuhtecuhtli, o “Señor de la Turquesa”, un joven dios del fuego, otorgó a los gobernantes mexicas el poder, y la responsabilidad, de impulsar el tiempo hacia adelante. La palabra náhuatl xihuitl significa “turquesa” pero también “año”, lo que relaciona a la deidad con el ciclo solar. Los festivales dedicados a Xiuhtecuhtli conmemoraban y protegían este ciclo. Cada cuatro años, en el festival de Xiuhtecuhtli en Tenochtitlan, el gobernante mexica adoptaba la vestimenta de la deidad y danzaba, encarnando su poder divino. Xiuhtecuhtli también presidía la importante ceremonia del Fuego Nuevo, o de la Unión de los Años, un rito que se celebraba cada cincuenta y dos años para mantener el viaje cíclico del sol y, por tanto, la era solar.

Xiuhtekuhtli, 1250–1521

Xiuhtekuhtli, noso “Señor de la Turquesa”, in telpokatl teotletsin, kimakalia tlahtoanimeh mexikah in hueltiyotl ihuan ixyektili, kahuinehnemi ixpanhuitsinko. In mexikatlahtoli xihuitl quihtosneki “chalchihuitl” auh noihki “xihuitl”, inin molhuia in teotl ihuan ika olin tonal. In ilhuimeh Xiuhtekuhtli moilnamikilis ihuan tlapialia inin olin. Sese nahui xihuitl, ipanin ilhuitl Xiuhtekuhtli Tenochtitlan, in Tlahtoani mexika kikui in teokentli ihuan mihtotilia, kikui teohueltiyotl. Xiuhtekuhtli noihki tlanahuatili yankuik tletl, noso xiuhmolpili, inin ilhuitl mochihua sese ompohuali onmatlakome xihuitl ipan monehnemilistli in olintonalnemi.

Xiuhtecuhtli, 1250–1521

Xiuhtecuhtli, ben lez zoa lha “Bene’ “yej tit mba”, to bene’ xkuide’ bda’o yi’, gwdixjoe’ che gwnhabia’ mexicas ka’ yesake’ bene’ walh, yesonyane’, yosose’ che lla lla shejen llia lhao. Dilla’ náhuatl xihuitl “yej tit mba” , dan lez zejé “iz”, lenna’ nhaken txhen lhen bene’ bda’on lhen zej shlhechj gwbill. Lni dan chhak che Xiuhtecuhtli lez nhaken lni che gwbill. Zelhao tapiz wejé, lo’ lni che Xiuhtecuhtli dan chhak lhatj Tenochtitlán, kanha’ bene’ gwnhabia’ mexicakan chhaze’ xha bda’on, nha’ chye’, chhonhe’ ka gwnhabia’ walh. Les Xiuhtecuhtli nha’ gwzoa lhawe lni llialhaon che Yi Kob, lni da’ chhotob iz, to lni wenab, da’ gosonhe’ zelhao shillineyon iz wejé ench kon ne nka’ xnez gwbillen chhechjen, ench kon ne yo’o Yelamban che gwbila’.

Vessel with Codex-Style Scene, 1350–1500

This vessel reproduces—in both form and design—the fundamental concepts of Mesoamerican land and lineage: a mountain atop a cave, through which flow the primordial waters of creation. Painted with remarkable artistry, this vase depicts a supernatural scene that envelopes its entire surface, including the base. The complex scene relates a story of creation, principally the birth of a yellow-haired culture hero and his subsequent ensoulment in a baptismal water rite. The narrative begins with two creator deities who converse in a stylized mountain within a personified cave. The fanged maw of the cave curls onto the base of the vessel.

Vasija con escena de estilo códice, 1350–1500

Esta vasija reproduce, tanto en su forma como en su diseño, conceptos fundamentales mesoamericanos sobre la tierra y su linaje mediante una imagen de una montaña sobre una cueva, por la que fluyen las aguas primordiales de la creación. Pintada con notable maestría, esta vasija representa una escena sobrenatural que envuelve toda su superficie, incluyendo su base. La compleja escena relata una historia de creación sobre el nacimiento de un héroe cultural de pelo amarillo y su posterior consagración en un rito de agua bautismal. La narración comienza con dos deidades creadoras que conversan en una montaña estilizada dentro de una cueva personificada. Las fauces colmilludas de la cueva se enroscan para abrirse en la base de la vasija.

Kaxitl amoxmixtekakopa, 1350–1500

Inin tepalkatl mochihua, masehualmachiotl ompa hueyi nepantlali itech in tlaltikpak ihuan isenyesmekayotl in tepetlaixkopina ostotikpan, nikan panoayan teoatsintle. Yeyetsin tlaihkuiloli, inin tepalkatl mahuisoixkopina ka tlayahualoa ihuan tsinko. In kopinalini nemilispohua itech otlakatilia in tlayekanki ika xilotsontli satepan ilhuitl temahmana atsin bautismal. In tlapohualpehua ika ome teotsitsin tlanonotsa tepetl ihuan tlaihtiko onka in tlakaostotl. In koatlanostotl moyahualoki ka tepalkatsinko.

Nhaken ka to ye’ne dan lo yish welhab golhe mixteca, 1350–1500

Sha’ dáo nhi shlho’en, kanha’ nhaken kanha’ nhonhen, katek xbaben gosonhe’ che Yelllhion lhen dialla che gake’ kate’ bosochhenhen to ya’a yichj yechho nhadjo, gan chhalh nhis walh wexe. Wapdáon bosochhengachhen, danhan shadáo nhi nllátelhe nhaken da’ ndoben doxhenhen sha nhi, nha’ lez ka’ xne’n. Kateken nchhenhenna zéjen chhoen dilla nhaken gok kate’ goljto to benebdao yichj gash che gake’, nha’ nhak gok bllie’ goke’ bene’ walh, bzoe’ le’ nhis la’y kate’ gwzi’ lhe’. Kate’ tsolhao dillan chwalan chop benebda’o soshalje’ to lo’ ya’a, dan nchhenhe’ wapdáo lo’ yechho nhadjw da’ zoa walhaz bene’. Llit chhoa’ loshj chho’a yechho nhadjon nka’ sjannka’ ljellen nha’ seyaljon chhoa’ xne shadáon.

Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes

When 16th-century Spanish authorities solicited maps to visualize the extent of their colonial control, Indigenous artists created something more: they turned to their dynamic cartographic traditions to produce living images that enlivened their connections to the land, their communal histories, and their legal right to contested territories. Mariana Castillo Deball and Sandy Rodriguez draw inspiration from these traditions, wielding mapmaking to challenge apolitical renderings of space.

Mixpantli: Ecos contemporáneos

Durante el siglo XVI las autoridades españolas solicitaron a las comunidades indígenas mapas de los nuevos territorios americanos con el objetivo de visualizar el alcance de su control colonial. Los artistas indígenas, en cambio, aprovecharon la situación para crear innumerables mapas en los que su propia tradición cartográfica reactualiza sus conexiones sagradas con la tierra, con sus milenarias historias locales, y con ello, logran tener instrumentos para negociar su derecho legal a los territorios en disputa. Las artistas contemporáneas Mariana Castillo Deball y Sandy Rodríguez se inspiran en la cartografía indígena para reflexionar sobre las capacidades narrativas, históricas y políticas de los mapas.

Mixpantli: Axkantikatsitsilikah

Itech XVI xihuitl in koyotekatetekuhtin okinnahuatihkeh in toltekatlakah (in nahuatlakah in tsapotekatlakah ihuan oksekintin) in toltekatlalan imachiyo inik yehuantin (in koyotekah) in koyotekah kihtaskeh in pehualtlali in pehualaltepetl. Otlamixkahuihkeh in toltekatlahkuilohkeh inmoketsalis ihuan okichiuhkeh miek amatlalixiptlayotl in impan in ika in itoltekaamatlalixiptlayomatilis okiyankuilihkeh inteotlanehnepanolis in ika totlalnan, in ika in tlahtolotl in ye huehkauh kinmatiayah, ihuan ika inon tlamatilistli okichiuhkeh in tlahtolketsalli tlamantli in ika okimanahuihkeh in tlali in altepetl in koyotekatlakah oteichtekkeh in toltekatlakah in toltekatlalpan. Ika in toltekaamatlalixiptlayomatilistli in axkan sihuatlahkuilohkeh Mariana Castillo Deball ihuan Sandy Rodríguez moyolpohuah in ken motlahtos itechpa tololi itechpa ketsaltlahtoli impampa in amatlalixiptlayomeh.

Mixpantli (Banderh bejw): Shi’ lla na’ lla

Iz gayoa XVI bene’ xtirh gwnhabia’ gwnabe’ lhao yell xhon yish ga nchhen lhatj yelllhio che gake’ ench nesde’ gaten zelhao gak che’ na’bie’. Nha’ bene’ wechhen xhon ka’ gosakbede’ chen, nha’ beseyiljwlhalle’ bosochhenhe’ zan koen yish da’ kobte ench gwlhoen kateken chhesejnhi’lhalle’ Yelllhion, kateken nhak dillagolh che gake’, kan gosak che’’ ench gota’ yish da’ ben lhatj bosollonhe’ Yelllhio chen da’ chhak dilde’ lhen bene’ yoblhe. Nholh wechhen lle’ na’ Mariana Castillo Deball nha’ Sandy Rodríguez gosebede’ kan nchhen yish xhon ka’ ench len gaklhenhen gonchho xbab nhakyanen nyoj lo’ yish nchhen na’ ka gok kanhi’ nha’ ka gosonhe’.

Mariana Castillo Deball

Vista de Ojos (Overview of the Eye), 2014

Deball’s etched floor, Vista de Ojos, places the viewer inside one of the most contested spaces: the first Indigenous cartographic representation of the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan under Spanish rule. The original map was painted around 1550. The map addresses with intelligent subtlety the contention between the colonizers and Indigenous life: While the new Spanish city is drawn as if frozen in time and empty of life, the lake and the mountains around it are filled with Indigenous people working, fishing, and walking through the land. Deball’s immense black floor with crisp white lines expands and summons history into the present. The contemporary viewer has to walk across the map to recognize the forms that comprise it, thus transforming the cartographic and historic space into a vision of the future: our present time.

Mariana Castillo Deball

Vista de Ojos, 2014

El piso grabado de Deball, Vista de ojos, sitúa al espectador dentro de uno de los espacios más disputados: la primera representación cartográfica indígena de la ciudad de México-Tenochtitlán bajo el dominio español. El mapa original fue pintado hacia 1550, y aborda con inteligente sutileza la discordia entre los colonizadores y la vida indígena. Mientras la nueva ciudad española aparece como si estuviera congelada en el tiempo y vaciada de vida, el lago y las montañas que la rodean están llenos de indígenas que trabajan, pescan y pasean. El inmenso piso negro de Deball, con nítidas líneas blancas, expande y convoca la historia en el presente. El espectador contemporáneo tiene que recorrer el mapa para reconocer las formas que lo componen, transformando el espacio cartográfico e histórico en una visión del futuro: nuestro tiempo presente.

Mariana Castillo Deball

In tlen kihta in teixtelolo (Vista de Ojos), 2014

In kampa monehnemi ihtik in kalli Deball, okiteokuitlaihkuilo se itekiuh in itoka In tlen kihta in teixtelolo, se tlamahuisoltlateokuitlaihkuilolistli in kampa mohta: inik se amatlalixiptlayotl itechpa in ye kipehuayah in kaxtiltekah in Tolan Mexihko Tenochtitlan. Okihkuilolo in tlatsintiloni amatlalixiptlayotl ahsoken 1550 (mahtlaksentzontli mahtlakexpoali nahui, xiuhtekpanalistli). Yektlamachtilistika techihtitia inin amatlalixiptlayotl in kampa mohta in ken nemiah in toltekatlatlakah itech in kampa nemiah in toltekapachoanimeh. Nesi papachkak, ahmo ika yolilistli, in yankuik kaxtiltekaaltepepetl, yese in tetepeh in kiyahualoah kaxtiltekaaltepepetl nesih itlok in toltekah in pakilistika tekitih, tlahtlamah, paxaloah. Kimoloniltia in tololi in tlatololhuia ixkichka in axkankayopan in huehhueyi tliltik ikalnepanol in Deball. Itech moneki in axkan tlaihtani tlaihmatilistika tlaihtas inik kinextis mochi in amatlalixiptlayotl ihuan ma kikuepa in amatlalixiptlayomatilistik yeyantli, in tololyeyentli in tlen onyes; in toaxkankayouh.

Mariana Castillo Deball

Nloe’ lhao (Vista de Ojos), 2014

Dan bchhen Deball, da’ nzi’ Nloe’ lhao, chzoaten be’n shna’ len, to lo’ lhatj da’ gosakdilchgoade’: yish nhéchho ga nchhen lhatj Yelllhio che benexhon Sita’, lhatjen nzi’ México-Tenochtitlán, kate’ ba senabia’ benextilhe len. Yish dowalhj lhatj Yelllhio nhi bosochhenhen ka 1550, nha’ shlhoen katez ka nhak bia’ ka nlla’ tsalhalle’ ka benextilhe ka benexhon. Danhan lhatj kob che benextilhen nhaken ka nhak da’ bi yo’ yelamban, nha’ yelhen nha’ ya’an nyechje nlladite benexhon chheson llin, bene’ sezi’ bél nha’ bene’ chhesashze nhi nhalhe. Da’ lhatj gasj xhen che Deball, da’ nkoachgoa nhez shish, chshiljon nha’ chhaxhen chhedezen kuitchho lla na’ lla ka gok kanhi’. Nha’ bene’ shna’ len na’, chhénhen shjasie’ lhawenna’ ench yeyombie’ koen koenhen, ench kon gakde’ shne’ yishen llan za’ gak ki: ka na’ lla.

Sandy Rodriguez

Rainbows, Grizzlies, and Snakes, Oh My! - Conquest to Caging in Los Angeles, 2019

Sandy Rodriguez also merges different times and spaces in her cartographic work, but through a different artistic device. Her maps are drawn as recognizable, modern representations of today’s contested territories: the US-Mexican border, the Western States of the US and California, and Los Angeles, where Rodriguez fuses present day events with imagery made by 16th-century painters to transform these maps into complex, multilayered images of history. In her practice Rodriguez adheres to an Indigenous way of understanding painting for she personally collects minerals, vegetables and flowers to transform the pigments she employs into tokens of the lands she is representing. In this way, Rodriguez brings the millenary Mesoamerican painting into the present.

Sandy Rodriguez

Rainbows, Grizzlies, and Snakes, Oh My! - Conquest to Caging in Los Angeles, 2019

Rodríguez también fusiona diferentes tiempos y espacios en su obra cartográfica, pero a través de un dispositivo artístico diferente. Sus mapas se dibujan como representaciones modernas y reconocibles de los territorios actuales en disputa: la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México, los estados del oeste de Estados Unidos, incluida California, y Los Ángeles, donde Rodríguez fusiona acontecimientos actuales con imágenes realizadas por pintores del siglo XVI para transformar estos mapas en imágenes complejas y de múltiples capas de la historia. En su práctica, Rodríguez se adhiere a una forma indígena de pintar: recoge minerales, vegetales y flores para transformar los pigmentos que emplea en símbolos de las tierras que representa. De este modo, Rodríguez continúa en el presente la tradición pictórica mesoamericana.

Sandy Rodriguez

Rainbows, Grizzlies, and Snakes, Oh My! - Conquest to Caging in Los Angeles, 2019

No Rodríguez kinechikoa okseki kahuitl okseki yeyantli ipan iamatlalixiptlayomatilistekiuh ika okse toltekatlamantli. Mohkuiloa in teamatlalixilptlayohuan ken axkan tlahkuilolistli in kampa teyolloh moahsi in axkan tlali: in altepenahuak innepantla in Tlateyohualnechikolispan in Mexihko, in Tlateyohualnechikolispan sihuatlampa tlateyohualtin, no ika California ihuan Los Ángeles in kampa kinechikoa in Rodríguez in axkan momochihualistli ika in ixiptlayotl in okihkuilohkeh XVI xiuhpohuali tlahkuilohkeh inik kinkuepaskeh inintin amatlalixiptlayomeh itechkopa se ixiptlayotl ika miek ixtli ihuan se tololi ika miek ixtli. Ipan imomostlahtekiuh, Rodríguez monechikoa in toltekatlakah inik kihkuilos: tepehpena, xiuhpehpena, xochipehpena; inik kipoyahuas in tlapali in ika kixiptlayotia in tlali in altepetl. Yuhki, Rodríguez axkan kihkuiloa in tlen −ihuan in ken− kihkuiloayah in huehue tokolhuan, in ahkihuan nemiah in huehue Toltekatlalpan.

Sandy Rodriguez

Rainbows, Grizzlies, and Snakes, Oh My! - Conquest to Caging in Los Angeles, 2019

Rodríguez nha’ nhonhe’ toz izen nha’ lhatjen, nha’ nchhenhen lo’ llin che’, nllá’ ka nhonhen. Yishen nchhenhen ka nhakse lhatjen gan chhesedilde’ lla na’ lla: lhatj ga nllag yell Shla’ Nhis nha’ yell Sita’, yell lhatje Shla’ Nhis, dan dé shlalhe gan chxhoa gwbill nha’ Los Angeles, lhatjé kin nchixe Rodríguezen da’ chhak na’ bchhenhe’ kan bosochhen wechhen iz xhen XVI te, nha’ beyonhen yish nllálhe da’ nchixe zan ka gok kanhi’. Kan chhonhe’, bezie’ kan bosochhen benexhon kanhite: chhotobe’ yejyoxh, lhako nha’ yej ench chheyaken ka chhen da’ chholhoe’ yo yelambankse. Danhan Rodríguez nha’ shchhenhe’ na’ lla kan bosochhen benexhon golhe goselle’ kanhité.

The exhibitions Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico and Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes are on view through June 12, 2022.