Today’s non-stop technological advances make the appearance of the moving sidewalk at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900 seem like an anachronistic and modest invention. However, for visitors to this World’s Fair at the cusp of the 20th century, the moving sidewalk—known in French as the trottoir roulant—was indeed a remarkable feat of engineering and innovation. People did not expect it possible to travel in space by simply standing still, while the ground beneath them moved, as if by magic. Although iterations of a moving sidewalk had been seen at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893 and at smaller exhibitions in both Paris and Berlin before then, the trottoir roulant at the 1900 Universal Exposition proved to be a much more sophisticated achievement than its predecessors, initiating an international appetite for this new form of transportation.

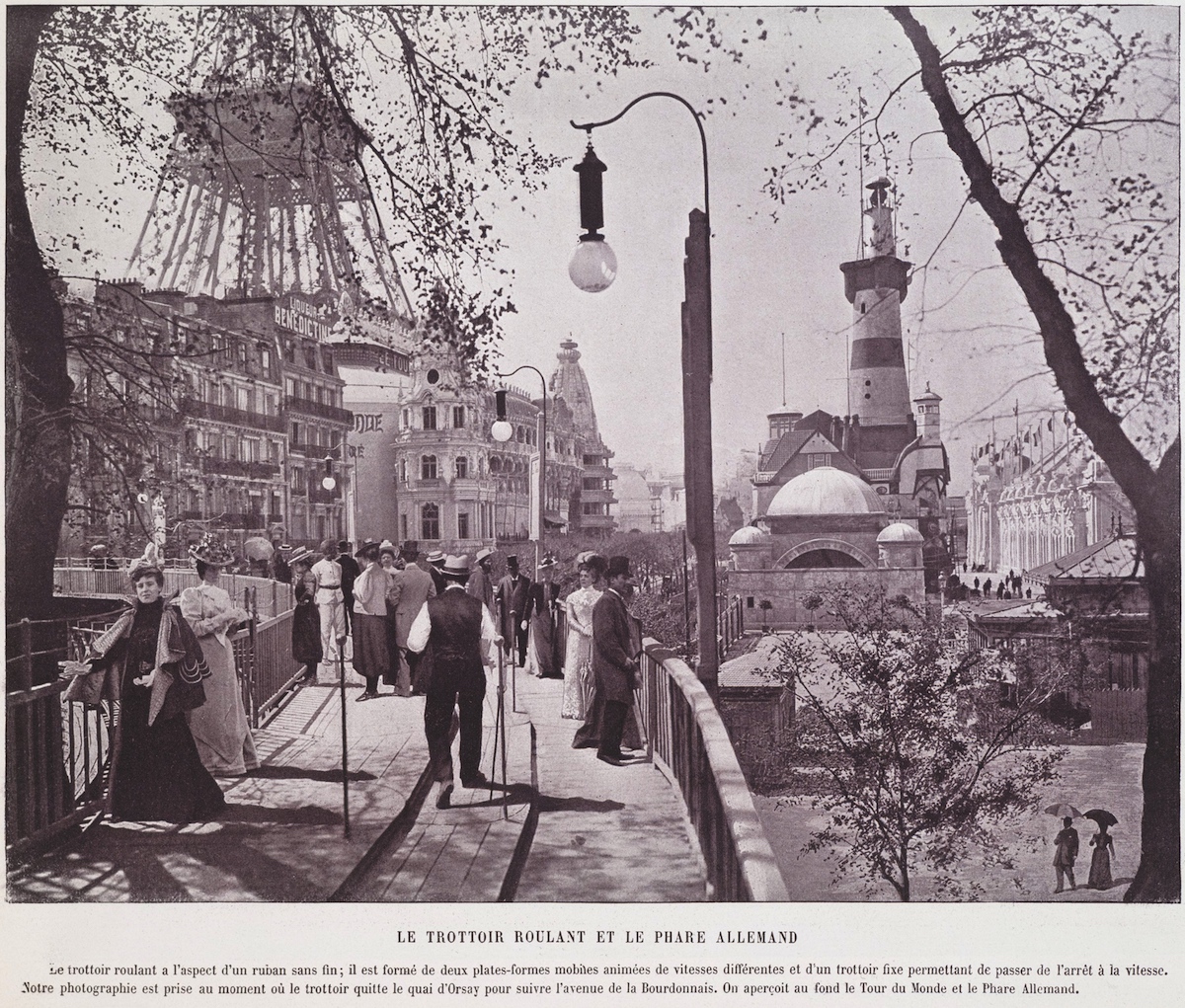

As noted by a New York Observer correspondent at the time, the moving sidewalk consisted of “three elevated platforms, the first being stationary, the second moving at a moderate rate of speed, and the third at the rate of about six miles an hour.” The moving sidewalk was a very popular component of the Parisian exposition, allowing visitors to literally take a break from walking, catching their breath as they could look at the sights, not actively walking themselves yet still moving forward to another part of the fair. Supported underneath by a 23-foot high iron viaduct encircling the perimeters of the fairgrounds, the trottoir roulant enabled visitors to circumnavigate the entire exposition contained within the 3.5 kilometer loop while standing still, an objective that could be realized in 26 minutes.

The Paris trottoir roulant was also called the Rue de l’Avenir (“street of the future”) and was designed by American architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee and American engineer Max E. Schmidt, who had also designed the Great Wharf Moving Sidewalk that had appeared at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. It could accommodate 14,000 people at one time and on one of the busiest days of the fair (Easter Sunday, April 15, 1900) it transported up to 70,000 people in an afternoon.

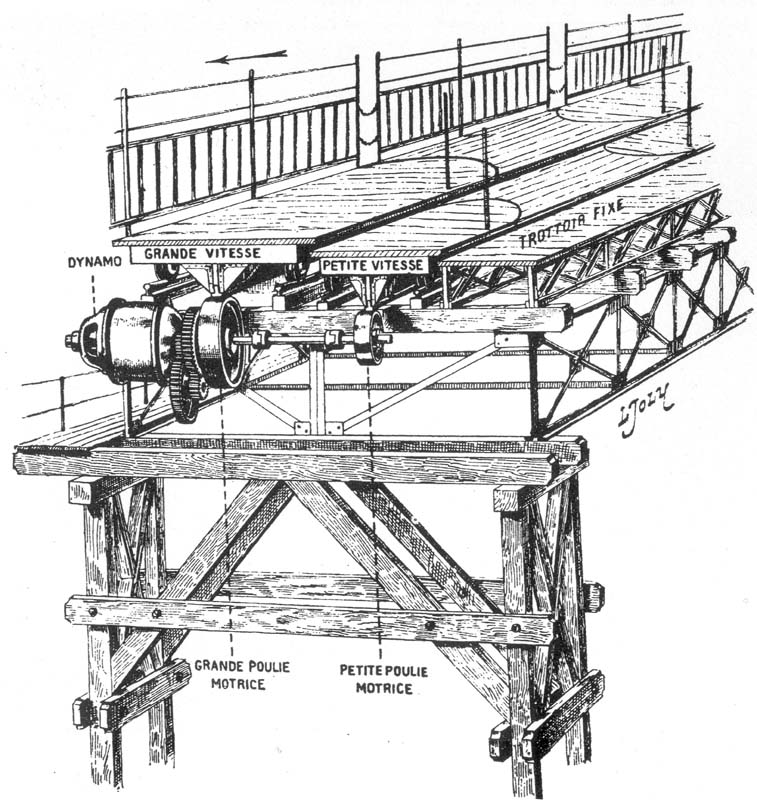

This diagram shows the three platforms as described above, with their mechanical structure illustrated below the surface: the first stationary walkway, the “Trottoir Fixe;” the second, the moderately mobile platform, the “Petite Vitesse;” and the uppermost and most rapidly moving component, the “Grande Vitesse.” The photograph below shows the elevated viaduct structure that supported the trottoir roulant.

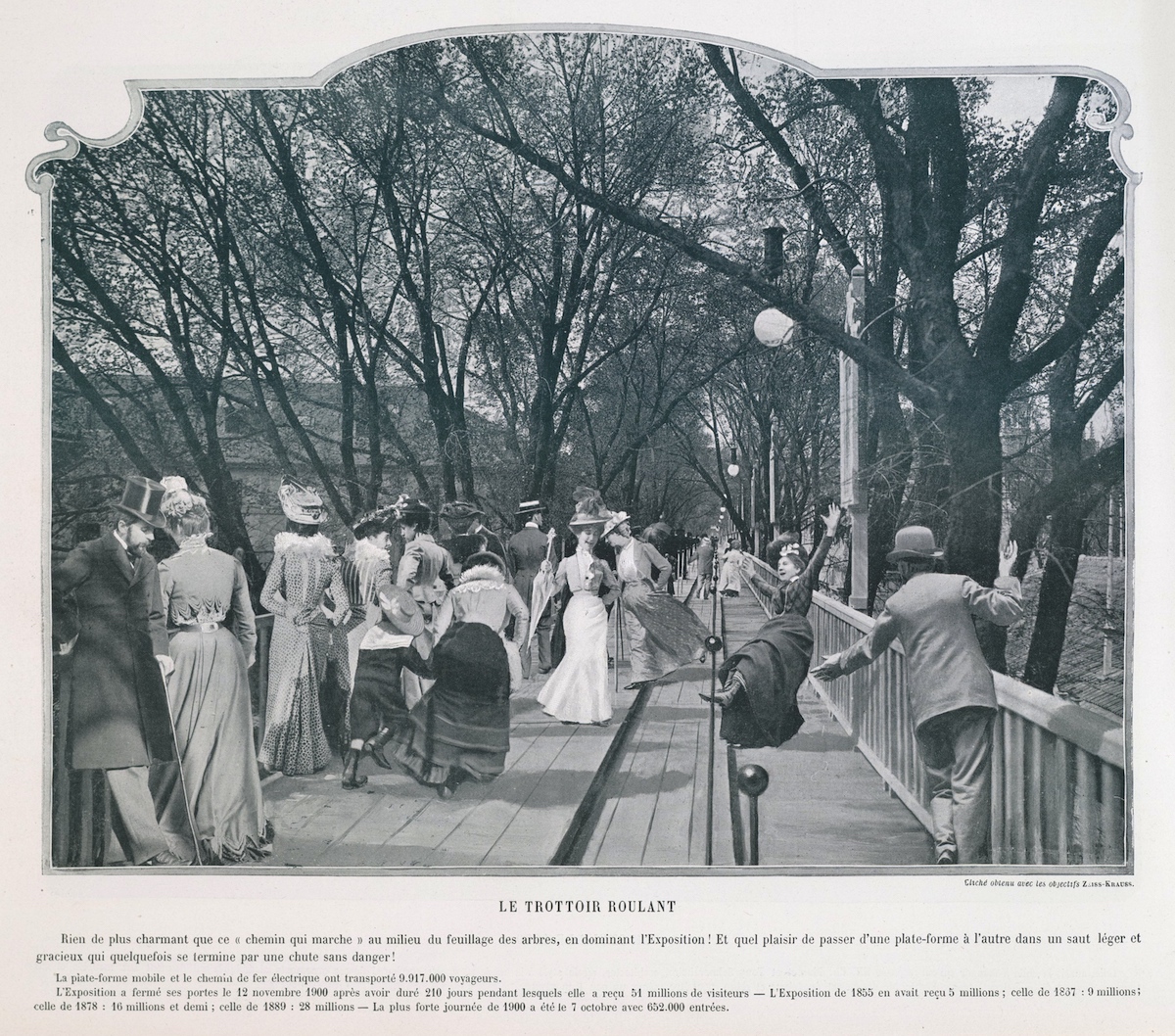

Although this innovative mode of transportation was avidly embraced by the public, there were also inherent dangers of which one needed to be mindful. Visitors had to learn how to safely step onto the moving platform and maintain their balance—this was a sensation unlike any they had felt before—and clothing had to be lifted out of the way so as not to cause the wearer to step onto the fabric and fall, injuring both the person involved and possibly causing a chain reaction of falls to happen to others in close proximity. The image below is not an actual photograph of an accident happening, but rather an imaginary—and slapstick—scene of what could happen.

"The motive of accidents on the Trottoir roulant came up over and over again in both texts and in graphic illustrations," writes Dr. Erkki Huhtamo, a media archaeologist, exhibition curator, and professor in the Department of Design Media Arts and Film, Television and Digital Media, UCLA. This often exposed a male chauvinist perspective and a stereotypical view on the frailty of women. "In a patronizing tone, Burton Holmes (1908: 233–235) claimed that stepping from the stationary platform to the mobile ones required ‘little skill’, but ‘nine women out of ten, with that innate feminine impulse to face the wrong way, found it impossible to effect a change of base without a stumble and a shriek’."

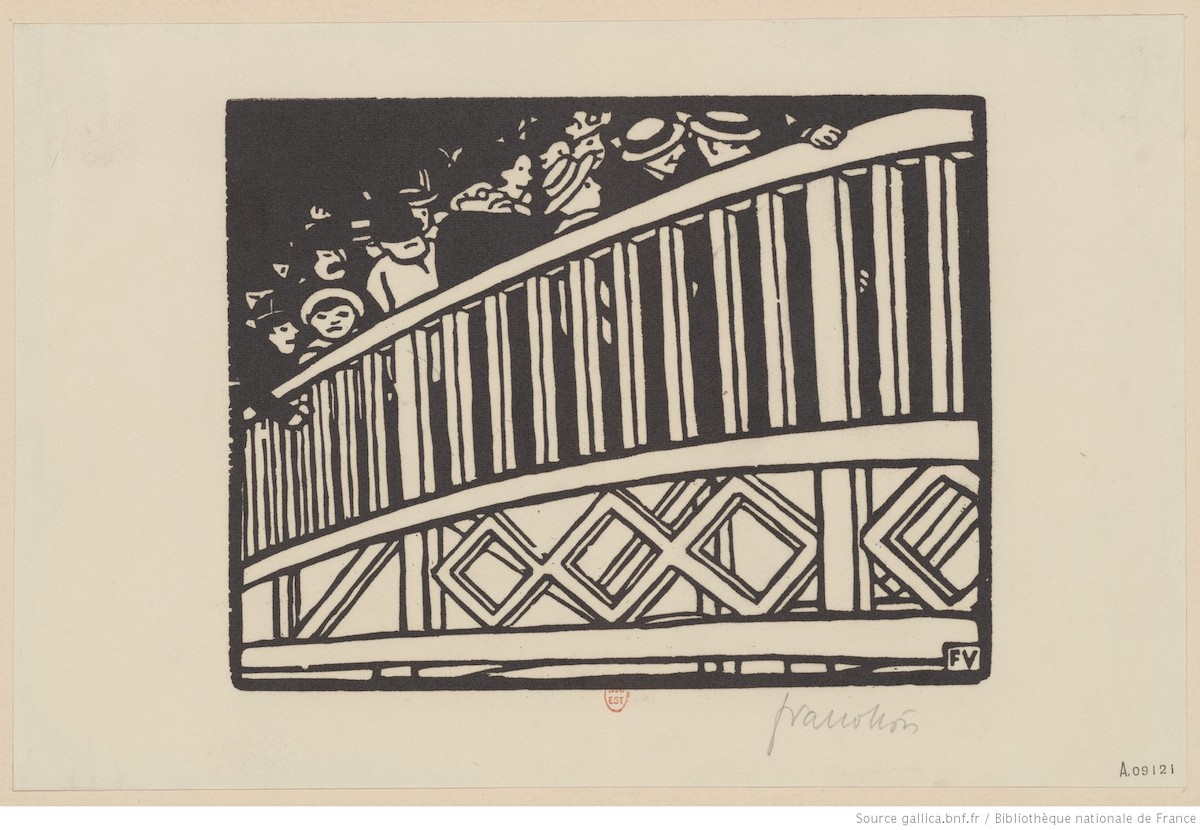

LACMA’s exhibition City of Cinema: Paris 1850–1907 includes numerous objects that illustrate the theme of the trottoir roulant, including the woodcut by Félix Vallotton from his series illustrating the Universal Exposition of 1900 from the collection of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts at the Hammer Museum, UCLA; a souvenir board game made during the exposition from the Getty Research Institute; and a watercolor on paper from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris by Maurice Denis, with a fan-like shape that in itself emphasizes a sense of movement for the viewer. The next time you are at an airport, standing on the long moving walkway as you connect from one terminal to another, remember that this is just the contemporary equivalent of the public transportation system that debuted in Paris in 1900.

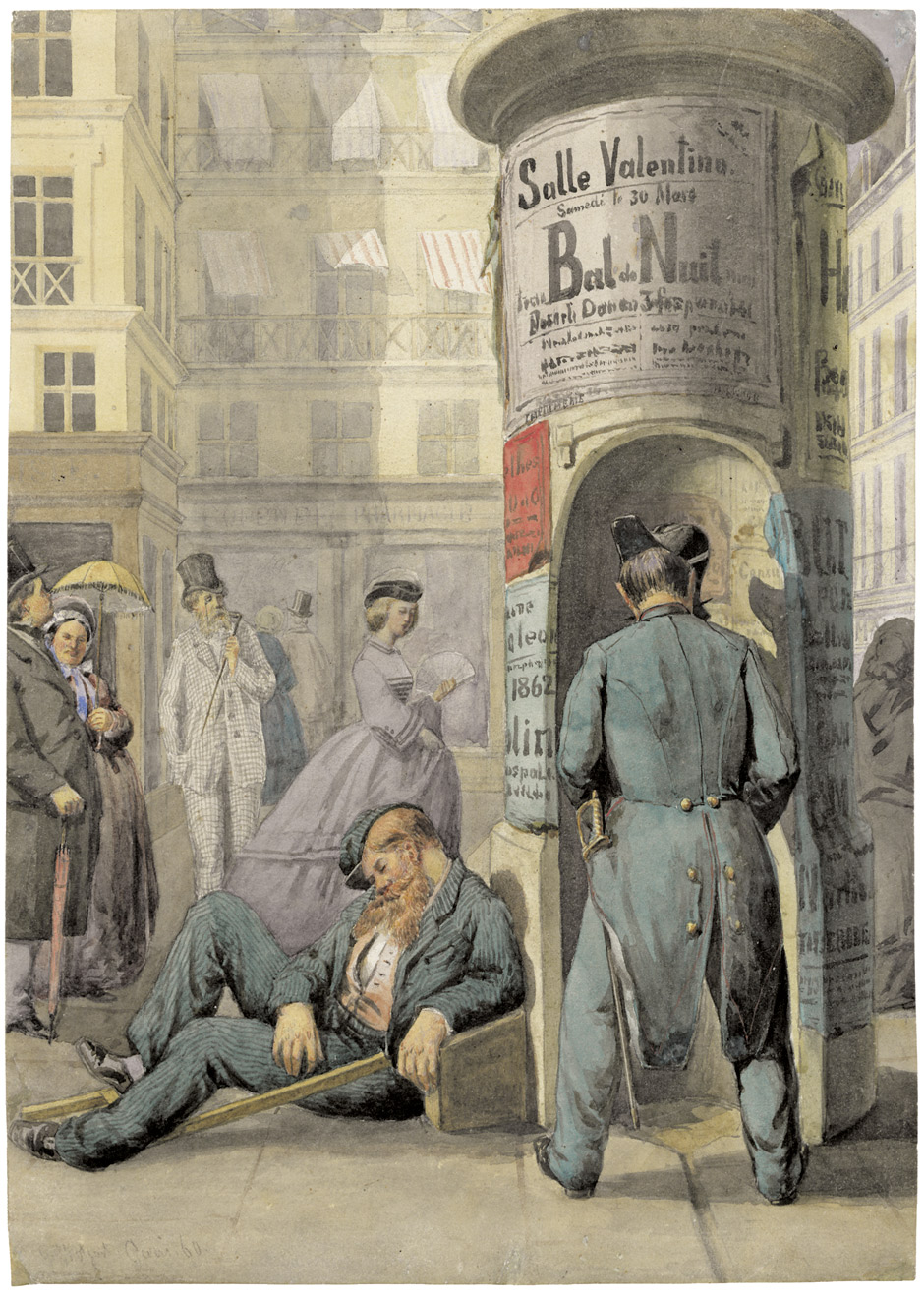

Another curiosity associated with fin-de-siècle Paris featured in City of Cinema is the Morris column—the green kiosk-like structures that you still see in the French capital and other cities which display poster advertisements. Originally conceived in 1868 by the French printer Gabriel Morris together with his son Richard, following their winning a competition by the City of Paris for the concession of exclusive advertising space, the Morris column was born from their desire to move away from the stench of the Paris pissoirs—also called vespasiennes (urinals), where exterior walls had also been used for pasting advertisements up to that time (as in the image above). Basing their design on the first advertising columns developed by the German printer Ernst Litfass, which had first appeared in Berlin in 1855, the Morris column became a vessel strictly limited to advertising purposes. Painted a uniform dark green in order to realistically blend with the treescaped boulevards and avenues of Paris, the Morris column is a hexagonal faceted column with an approximate surface area of 14 feet and, with its signature domed-like cap, reaches a height of 20.5 feet. The awning above the column surface is decorated with scales and acanthus leaves and a round strip below the awning contains the words “Spectacles” and “Théâtre,” separated by a medallion with a boat, which represents the city of Paris’s motto in Latin, “Fluctuat nec mergitur” (literally, “it is tossed by waves, but does not sink”)—a symbol of strength and resilience for the French capital.

Morris columns provided a platform to display the burgeoning production of posters made to advertise entertainment performances in Paris, ranging from theater and dance to music concerts and multimedia spectacles. Their surfaces were covered with these disposable graphic announcements and illustrations, with so many posters destroyed over time that the few still remaining are now eagerly sought after by collectors and graphic design museums.

Within 20 years of their first appearance in Paris in 1868, some 450 Morris columns were constructed. Now, some 150 years later, columns based on the Morris design continue to be manufactured—in cities around the world—often utilizing more sustainable products. The multinational corporation based in France, JCDecaux Group, is ubiquitous throughout the world today for its billboards and bus- and tram-stop advertising systems and offers an interesting Gallic parallel to the development of the Morris column. Its founder, Jean-Claude Decaux, formed the company that carries his name at age 18 in 1955, inspired by his teenage entrepreneurial imagination in placing promotional posters for his family’s store and other local businesses in Beauvais, some 75 kilometers north of Paris. In 1964 he formulated a concept for advertising on street furniture (bus-stop benches, for example) and for building bus shelters that could also serve as platforms for advertisements and thus invented free-of-charge bus shelters that were managed and maintained by his company, wholly financed through advertising. Today, the JCDecaux brand is visible in transport hubs and billboards in over 75 countries around the world. The creation of the Morris column in Paris and its important role in advertising must thus be considered as a major impetus in the development of modern advertising on a global scale.

The exhibition City of Cinema: Paris 1890–1907 is on view through July 10, 2022.