Alan Rath is an electronic sculpture artist who blurs the boundaries between the organic and the technological by imbuing machines with playful curiosity and life-like movements. Born in 1959 in Cincinnati, Ohio, Rath grew up during the Space Race and took aesthetic inspiration from the lunar lander, control panels, and Jimmy Hendrix. He resided in San Francisco for the majority of his career and passed away in 2020.

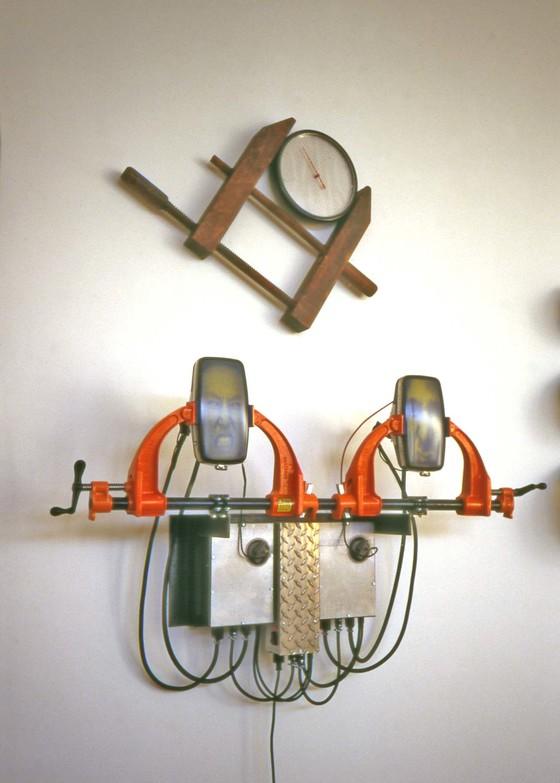

LACMA acquired one of Rath’s robotic sculptures Togetherness II (1995) in 2001. The work consists of an eclectic mix of machinery, two 9 × 5 inch monochrome CRT screens, and a clock with only a second hand, suspended by a wooden clamp. Rath took footage of himself and his wife’s faces and presented them in the CRT screens. Their faces are squished into frame, appearing as though they are shouting at one another across an orange metal apparatus that holds the two apart at a safe distance.

Togetherness II is a unique object in the collection with a sci-fi aesthetic that would stop any exhibition goer in their tracks. The only problem is this piece has not been plugged in for 20 years.

I spoke with LACMA’s Objects Conservation Intern Adrian Hernandez, who spent the summer researching Togetherness II and Alan Rath’s art practice in order to revive the machine. He discovered that Rath meticulously documented the engineering of his pieces and created care instructions for preservation purposes.

Hernandez also discovered that the video feed for the screens are not recordings, but rather an animation of several still images stored on EPROM chips within the hardware. Rath typically animated his moving images with the circuitry of his machines, rather than using recorded video. Sometimes he used algorithms to randomize the order of images to replicate organic reactive movements.

Hernandez was able to view copies of the files stored inside the piece, which were generously provided by Rath’s estate. He also carried out a close visual examination and condition assessment of the circuit boards. With this research in hand, on August 15, 2022, Hernandez sought to bring Togetherness II back to life.

I joined Hernandez to see the piece. When I entered the Object Conservation lab, I saw an ancient stone sculpture being examined, a Celtic metal helmet on a rolling cart, and a stained glass window on a table being pieced back together. In the middle of the room, I saw Rath’s orange and silver machine with cables hanging and gray screens awaiting electrification.

A small audience of conservators paused their work to watch. As Hernandez retrieved the cord and plugged it into a socket below the table, everyone stood still for a moment with bated breath and eyes fixed on the two little screens. The screens then flashed to life with the faces of Alan Rath and Mia Jang. The images were still at first, the faces gritting their teeth, and then began to move like they were snarling or chattering their teeth at one another.

The small gathering fluttered about the machine deducing the condition of the electronics as the amber CRTs glowed steadily. Not a minute later, the left screen featuring Rath's face grew much brighter, and vertical stripes appeared across his snarled expression. Hernandez promptly unplugged the sculpture as a precaution, and with that the screens grew dark. I exhaled for the first time in that whole two minutes that the piece was alive.

There are unique risks for art that utilizes technology, as the components can grow faulty if not properly maintained with regular operation—a unique conservation challenge that’s not part of the regular routine with oil paintings or stone statues. Although Togetherness II may not be ready for exhibition yet, electrical technicians and art conservators will continue to collaborate to share it with the public at LACMA.

Rath’s work may subvert our hostilities towards robots. His machines are playfully alive with their curious and fluid movement patterns that are unlike the cold and often dangerous actions of robots in media. He exposes the machine’s mechanisms to give us a sense of how they operate. They appear simple and handmade but still shrouded in magic. Rath never looked at technology as being so disconnected from the human experience. He compared his machines with objects that human beings have personal connections with like musical instruments.

In an interview with SFGATE in 1998, Rath said: “Our consciousness is fundamentally altered because we grew up in an artificial environment. Due to the plasticity of the human mind we don't see it as being artificial because we grew up in it. Somehow at a certain age the brain hardens and new changes seem alien. But machinery is not unnatural. It's a reflection of the people who make it.” Togetherness II serves as a reflection of a very human experience—relationships. It reminds us just how trivial spats in a long-term commitment can be because, if it's by love or by electrical wires, something eternally binds two people together.