Reexamining the Grotesque: Selections from the Robert Gore Rifkind Collection, which I curated as a 2021–2022 Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow at LACMA, opened in September 2022 in the Modern Art Galleries.

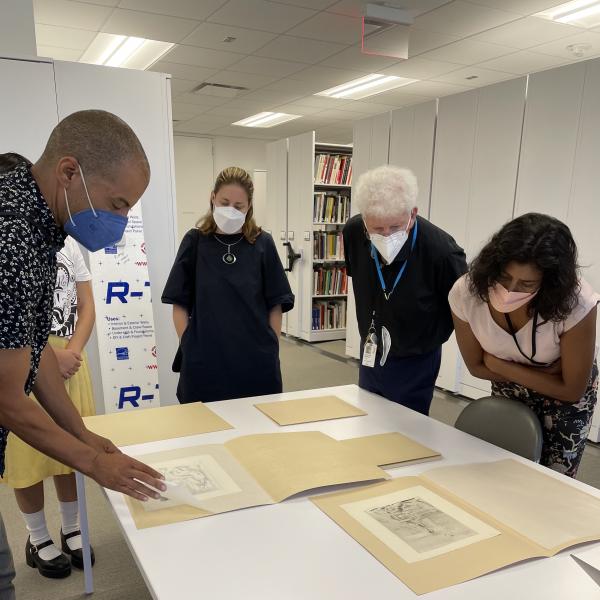

I began working in the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies in the fall of 2021. The Rifkind Center is located next to LACMA’s Balch Art Research Library, on the third floor of the 5900 Wilshire Boulevard building. It houses one of the largest collections of German Expressionist work on paper. I was excited to be working with Assistant Curator Erin Sullivan Maynes and Curator Tim Benson. After two weeks in my fellowship, I was given the opportunity to curate an upcoming gallery rotation using works from the collection. Unlike the majority of LACMA’s collection, which is stored offsite, the Rifkind Collection is located in the Rifkind Center and is accessible to the public by appointment. This meant I could actually get a close-up look of the objects, as well as touch and feel each piece. I started to collect my images in TMS (The Museum System, our collections management system) to create a theme.

After finding several interesting images, I decided the theme of the exhibition would be the grotesque, which would allow me to look back at history from a contemporary perspective. The grotesque is a means of exaggeration to reveal an underlying truth. It can be funny and satirical, or it can explore fears and anxieties. Art can also become grotesque when the values it depicts represent a racist or discriminatory worldview. Acknowledging this is important, as is understanding the ways that the past has shaped the present.

The grotesque was a strong undercurrent of art produced in Germany in the early 20th century. Some tendencies in Expressionist art, such as distortion or exaggeration, were already consonant with the grotesque, but it became particularly popular as individuals confronted the upheavals of modern life and the horrors of World War I.

The grotesque aesthetic can be a way of understanding Modernism and connecting it to debates about marginalization and “otherness.” Within the theme of the grotesque, I created sub-themes with different examples of the aesthetic. Some of the images deal with problematic concepts, as you’ll see, and I knew they would require didactic texts which would lend context to why I chose them.

The first sub-theme was disturbing for me. These were misogynistic images of violence against women. When looking at images like these, the first question that comes to mind for me is: why, as an artist, would you create this type of image?

I found a particular image which is a graphite, ink, and watercolor by Oskar Kokoschka titled Murder of a Woman, study for “Murderer, Hope of Women” from 1909. Writers such as Carl Vogt, Otto Weininger, and Friedrich Nietzsche exemplified an anti-feminine worldview that many popular artists and scholars held at this time. The influence of the fin de siècle in art, science, and literature reinforced these same ideas. The serial killer Jack the Ripper murdered women in 1888. Artists explored ideas of sex and death through the demonization and objectification of women. Oscar Kokoshka’s nude drawings interpreted the relationship between man and woman through a mixture of sexual desire and violence.

At the turn of the 20th century, anxieties around the changing roles of women were sometimes expressed through extreme, misogynistic imagery such as this. Kokoschka explored the connection between desire and violence in a play also titled Murderer, Hope of Women. The woman—named only “Woman”—is a femme fatale, or fatal woman, whom a man ultimately kills, and thus, defeats. Cultural attitudes that linked male dominance with female death surfaced in these types of depictions of Lustmord, or sex murder images. Such representations embodied male fantasies and fears on the violated bodies of women.

The next sub-theme focuses on dehumanizing imagery. In his poster titled Bolshevism Brings War, Unemployment, and Famine from 1918, for example, Julius Ussy Engelhard depicts a figure with animalistic features.

During the 1900s, such propagandistic images in Europe dehumanized certain groups in both art and mass media. Depictions of bestial or barbarian-like figures portrayed some people as uncivilized and wild, or as caricatures with demonic features. These illustrations often have blood on the hands or mouth of the figure. Historically, dehumanization is connected to genocidal conflicts. Engelhard’s poster was meant to show the threat of Bolshevism—the precursor to the Communist Party—in Germany. In this image, the threat is portrayed as a savage menace. Propaganda that dehumanized the enemy was used during World War I by all belligerent nations; an infamous American poster depicted the German soldier as an ape with spiked helmet and bloody club. Here, German right-wing propaganda adopts the same strategy to demonize political opponents, a strategy that would be used repeatedly during the Nazi era. This strategy is still used today in language and imagery to demonize certain groups, such as immigrants, all over the world.

Another sub-theme is the war-wounded. Several of the artists featured in this exhibition fought in World War I and were confronted by its horrors. One image that resonated with me was an etching and aquatint by Otto Dix titled Skin Graft, from the portfolio Der Krieg (War), from 1924.

The term “shell shock” was actually coined during World War I to describe the mental trauma caused by the conflict. “PTSD” (post-traumatic stress disorder) did not enter our vocabulary until 1980. The destructiveness of modern weaponry was as unprecedented then, as today's weapons are now. Here, Dix portrays a soldier who has had a skin graft to repair parts of his damaged face. The increasing damage inflicted on bodies and minds through war is mitigated by advances in battlefield medicine that saves more lives, and this image depicts this paradox: a soldier with a head wound survives, but is disfigured for life. Not all wounds are so visible. Many artists also suffered from emotional and mental stress following their battlefield experiences.

The next sub-theme I explored in this exhibition is killing at a distance. Another etching by Otto Dix titled House Destroyed by Aerial Bombs, also from the portfolio War, echoes the true nature of war technology.

Dix enlisted as an artillery gunner during World War I and served on the Western Front. Ten years later, he created a portfolio of 50 prints, Der Krieg (War), that processed the full horror of the experience. This print from Der Krieg depicts the aftermath of an aerial bombing on a civilian area. Such battlefield tactics, and the resulting civilian deaths, were unprecedented at the time, but have since become familiar; indeed, Dix’s image evokes countless conflicts ever since. As weapons technology enables killing at a greater distance, civilians end up as collateral damage, unseen by the people pulling the trigger. The imagery in House Destroyed by Aerial Bombs is disturbingly familiar today. As John Govern, a West Point cadet, wrote in his 2016 essay “The Importance of Distance In Modern Warfare”: “The quest to distance oneself further and further from the most basic act of war, killing, is nearing its apex.” The acceptance of civilians as collateral damage has also increased as the weapons used in battle have become more advanced. In the book Air Power and War Rights (1924), J. M. Spaights writes: “Attacks on towns will be the war. The side that attacks the enemy's cities with the heaviest hand and greatest success will win.”

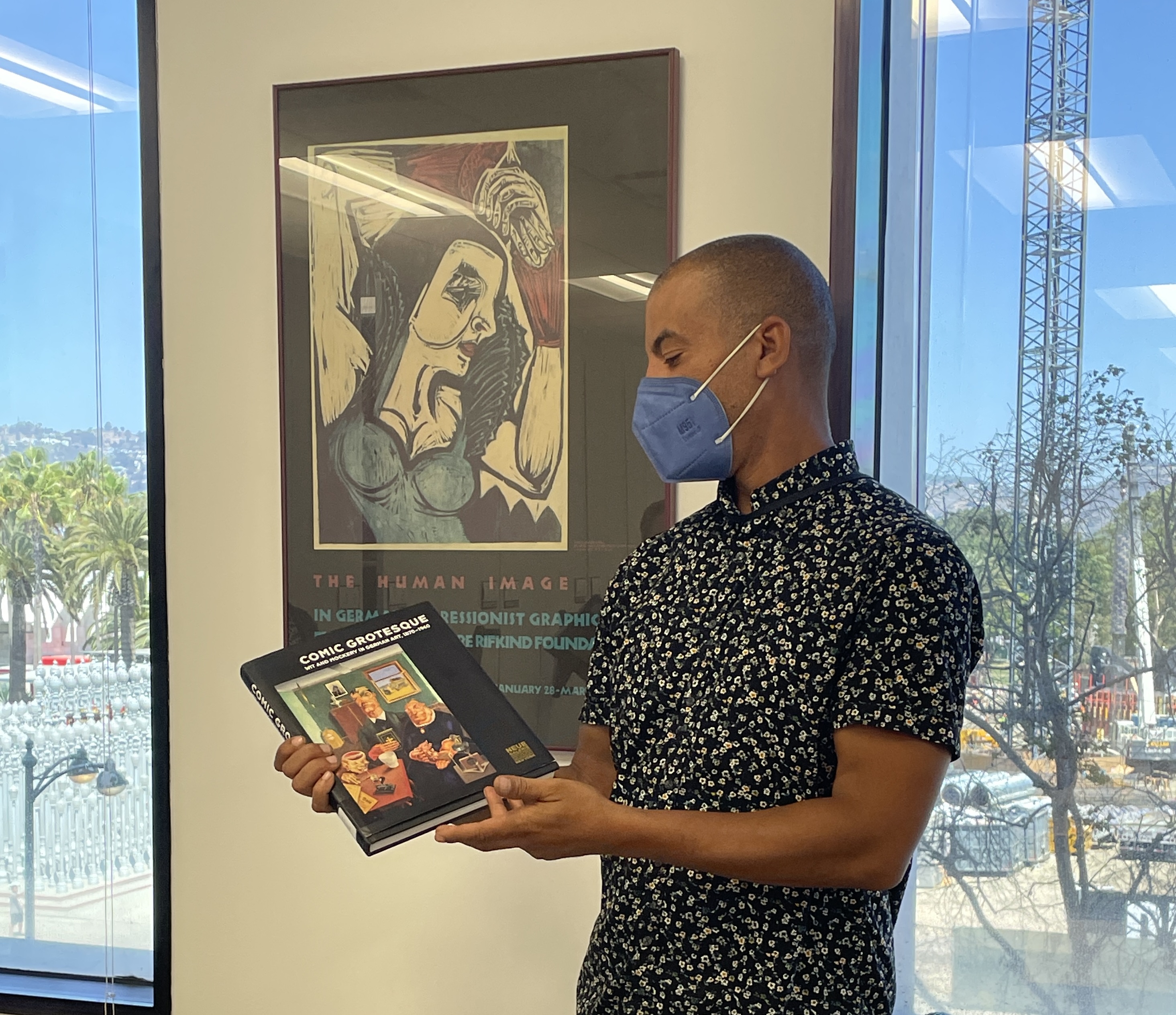

Within the exhibition I did also want to include something with a lighter tone. A style of the grotesque some viewers might be familiar with is known as the comic grotesque, or caricature. I found a perfect example in a lithograph by Georg Scholz titled Industrial Peasants, created in 1920.

Influences of the comic grotesque came from Berlin nightlife as well as satirical journals, cabaret theater culture, and tragicomedies. While sinister and gruesome, the grotesque can also be humorous. In Industrial Peasants, Scholz satirizes the distance between the romantic ideal of the traditional family farm and the reality of rural life. His farmers are cruel, greedy, and empty-headed. The pious father has money, not God, on his mind; the mother cradles a pig; the boy tortures a frog. Scholz resented the hypocrisy of rural workers who refused to sell more of their crops to starving cities at the end of World War I and instead hoarded food to drive up prices. His industrial farmers present as conservative and traditional, but are in reality self-serving and venal.

Along the journey of researching, selecting images, and brainstorming a theme, I met with the LACMA design team several times. We met with the Conservation department to make sure the images were in good condition. We also met with the framing team to see if there were changes needed. The rotations for this particular gallery happen every four to six months, which means there’s a pretty quick turnaround between exhibitions. From day one, I was given valuable advice from Tim, Erin, and the design team. We collaborated on the didactic panels, came up with a title, and will meet with the design team in the gallery next week.

I wanted to use the grotesque aesthetic in its different forms to create a provocative and thoughtful exhibition that would spark dialogue. The show was curated with the intention of encouraging the viewer to reflect on the history of these images and how they relate to our contemporary issues, like wars around the world; the attack on Otherness; the overturning of Roe v. Wade; the dehumanization of immigrants; and anti-Blackness, which all intersect in these images. How much has changed? How much has stayed the same? I leave you with these thoughts and hope you visit the exhibition, now on view through early March 2023 in the Modern Art Galleries in BCAM, Level 3.