On November 20, 1910, a call to arms united supporters in Mexico to rise up against the authoritarian regime of Porfirio Díaz and establish a democratic republic. Though Díaz—who had held power for almost 35 years—was not overthrown on that day, he resigned under pressure the following May. Nevertheless, this momentous event is recognized as the start of the Mexican Revolution, which lasted over the next ten years as competing groups struggled to gain power and advance political and social reforms. Eight years later, on November 3, 1918, a group of sailors in Kiel, Germany, refused to continue hopelessly fighting and dying as World War I came to an end. They mutinied, sparking a nationwide revolt that led to the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the declaration of the German Republic on November 9.

These experiences of revolution inspired the development of bold and innovative graphic practices in both countries. Now on view at Charles White Elementary School, Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany examines the shared subjects and visual strategies as artists responded to their respective upheavals and turned to printmaking to inspire and influence the public. Pressing Politics juxtaposes Mexican and German works in sections highlighting their shared themes: revolutionary contexts, politics and propaganda, labor, and solidarity against war. In honor of November’s historic revolutionary moments, this post explores two works from the exhibition that respond to their times of social and political transformation.

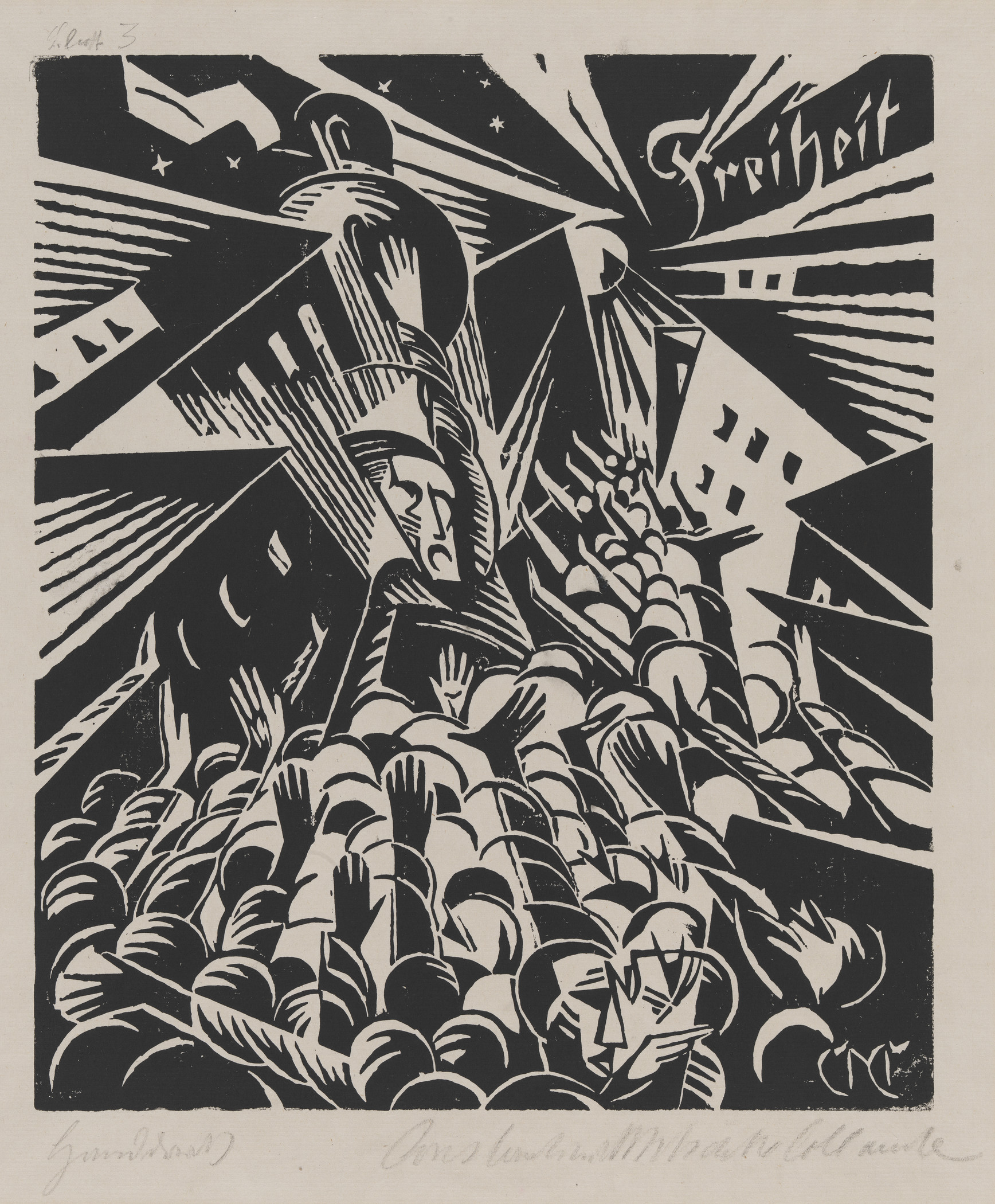

This woodcut by Constantin von Mitschke-Collande (1884–1956) is from a portfolio illustrating Walther Georg Hartmann’s short story Der begeisterte Weg (The Inspired Path). The story follows a soldier who leaves the fighting at the front during World War I and comes upon a revolution in progress, joining the side of the revolutionaries. Freedom (Freiheit) depicts the moment when the revolutionaries enter the city. The image’s energy is generated through the sharp diagonals of the crowd’s outstretched arms and the acute angles of the rooftops above. This energy converges around the upraised hand of the figure rallying the masses below and toward the celestial body on the upper right, harmonizing the earthly and extraterrestrial. Mitschke-Collande grew up in a wealthy German family but became an ardent member of the Communist Party. Freedom, created shortly after the start of the revolution, epitomizes the metaphysical side of revolutionary Expressionism. For many German artists, the revolution promised the rebirth not only of the German nation, but of humankind itself. This quasi-religious outlook accorded with an existing spiritual strain in Expressionism and with the political passions of the moment.

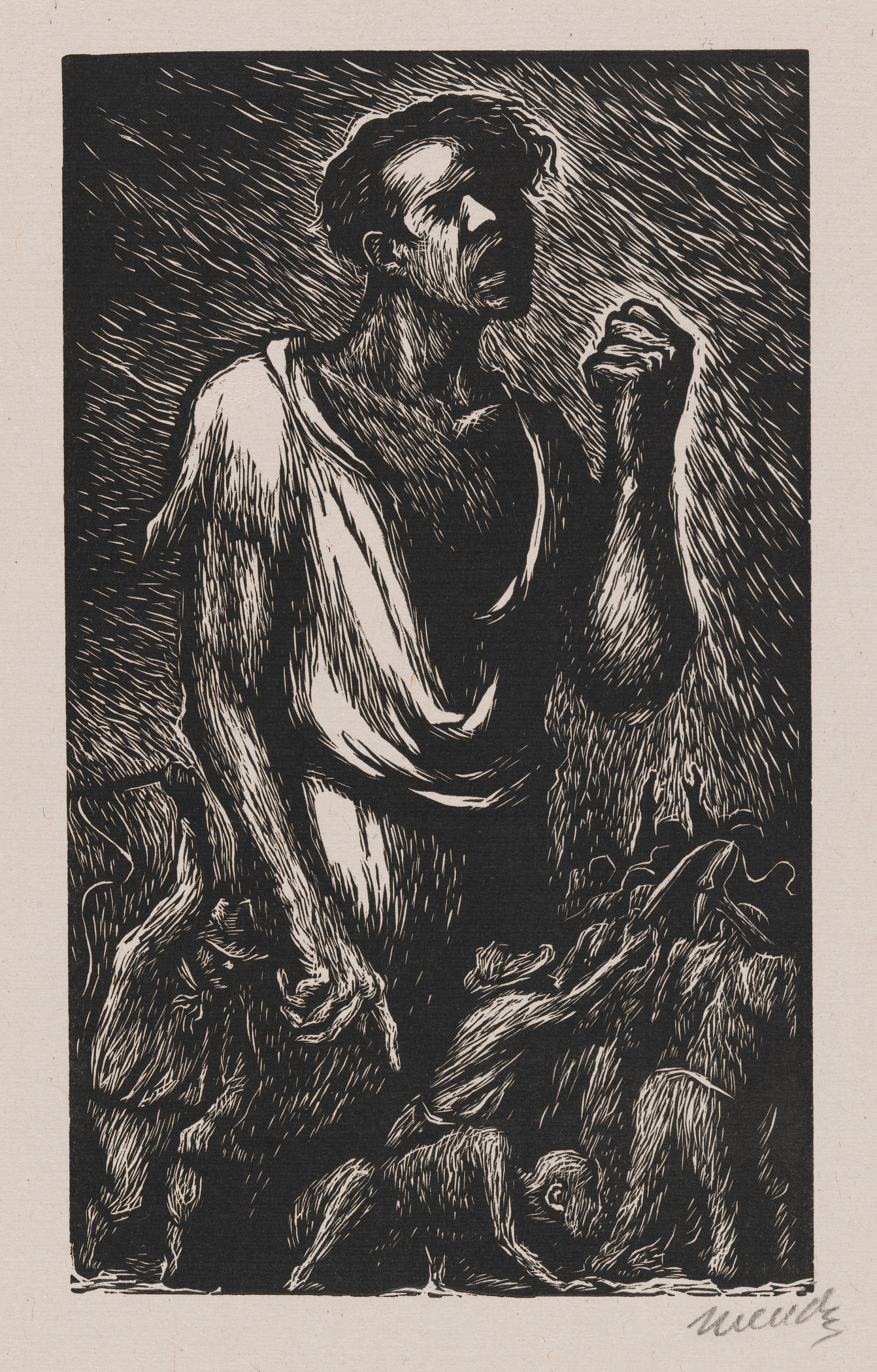

In 1937 a group of politically engaged artists founded the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Print Workshop; TGP) in Mexico City. The workshop aimed to use prints to continue to advance changes and social reform fostered by the Mexican Revolution. One of the TGP’s founders, Leopoldo Méndez, created this woodcut that same year. In Protest, Méndez plays with scale as a narrative and compositional device. The large central figure clenching his fist represents the people, confronting their oppressors. Below him, in a scene rendered much smaller, his comrades fall victim to men with whips. The gargantuan protester emerges from these injustices, emboldened by the collective power of his peers and visualizing the strength of their numbers. In 1943 the print appeared in a portfolio of Méndez’s work published by La Estampa Mexicana, the TGP’s in-house publisher, extending the reach of this potent image and its revolutionary message.

Mitschke-Collande and Méndez both communicate the moment of uprising through the upraised hands of their protagonists, who rally the masses to follow. This iconographic motif is prevalent throughout Pressing Politics and imagery associated with the revolutions we commemorate this November.

Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany is now on view at the Charles White Elementary School Gallery and is open to the public Saturdays from 1–4 pm. Portions of this blog are excerpted from the exhibition catalogue, available at the LACMA Store.