I first became interested in casta paintings in the early 1990s, when I saw an exhibition of these enthralling works at the Museo Franz Mayer in Mexico City. I grew up in Mexico but had been living abroad for some time and the paintings, with their collection of local foodstuff and other items, appealed directly to a sense of longing for my homeland. At first, the appeal was visceral—as are so many things that we are drawn to—and then became a lifelong intellectual pursuit. I’ve written and talked about these works extensively over the years, and I’ve always been reluctant to provide a definitive or closed interpretation of the pictures. While the paintings are part of a distinctive genre, they span an entire century (from roughly 1711 to 1810) and present intriguing variants; it’s natural that they would reflect the shifting times inasmuch as the desire of the patrons who commissioned them and the artists who created them. Both groups had agency. In addition, I’ve always been mindful that the way viewers interpreted the images in their own time depended largely on their own cultural baggage and agenda, on what they wished to convey to those with no direct experience of Mexico or New Spain, a “Spanish” outpost all the way across the Atlantic. The same happens today: viewers see the paintings differently based on their historical background, lived experience, and personal sensibility. But the more we can root ourselves in history and grasp the time when the pictures were created, the more we can understand our own position and perception of them today.

In broad terms, casta paintings portray the complex process of racial mixing among the three major groups that inhabited the viceroyalty of New Spain—Amerindians, Spaniards, and Africans. (There is also a well-known set produced in the viceroyalty of Peru.) Most works were created as sets of 16 scenes (although the number could vary). Each scene depicts a family group with parents of different races and one or two of their children. At the beginning or top of the series are figures of “pure” race (that is, Spaniards), lavishly dressed and engaged in occupations or leisure activities that indicate their higher standing. As the family groups become more mixed, their social status diminishes. The basic premise of the genre, as conveyed through the paintings’ inscriptions, is that the successive combinations of Spaniards and Indians (the latter were considered “pure” according to colonial legislation) would result in a vigorous race of unadulterated white Spaniards in the third generation. The mixing of Spaniards and Indians with Africans, however, would lead only to racial degeneration and the impossibility of returning to a white racial pole, as emphasized by zoological and other derogative labels such as “coyote,” “return backwards,” or “I don’t understand you.”

It’s rewarding to see that after I organized the first exhibition on the topic in the United Stated at the Americas Society Art Gallery in 1996, followed by a monograph on the genre and a larger exhibition at LACMA in 2004, the works continue to elicit much attention and interest from scholars. Many contemporary artists (among them Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, Joey Terril, and Emilia Azcárate) also continue to respond to the paintings through their work, decoding their purported taxonomic system to cast into relief how colonial bodies have been racialized and objectified over time, the origin of current racial ideologies and gender biases, and to poke fun at a system that at times seems hopelessly absurd and yet has had a real hand in shaping people’s perceptions of reality and the allocation of power.

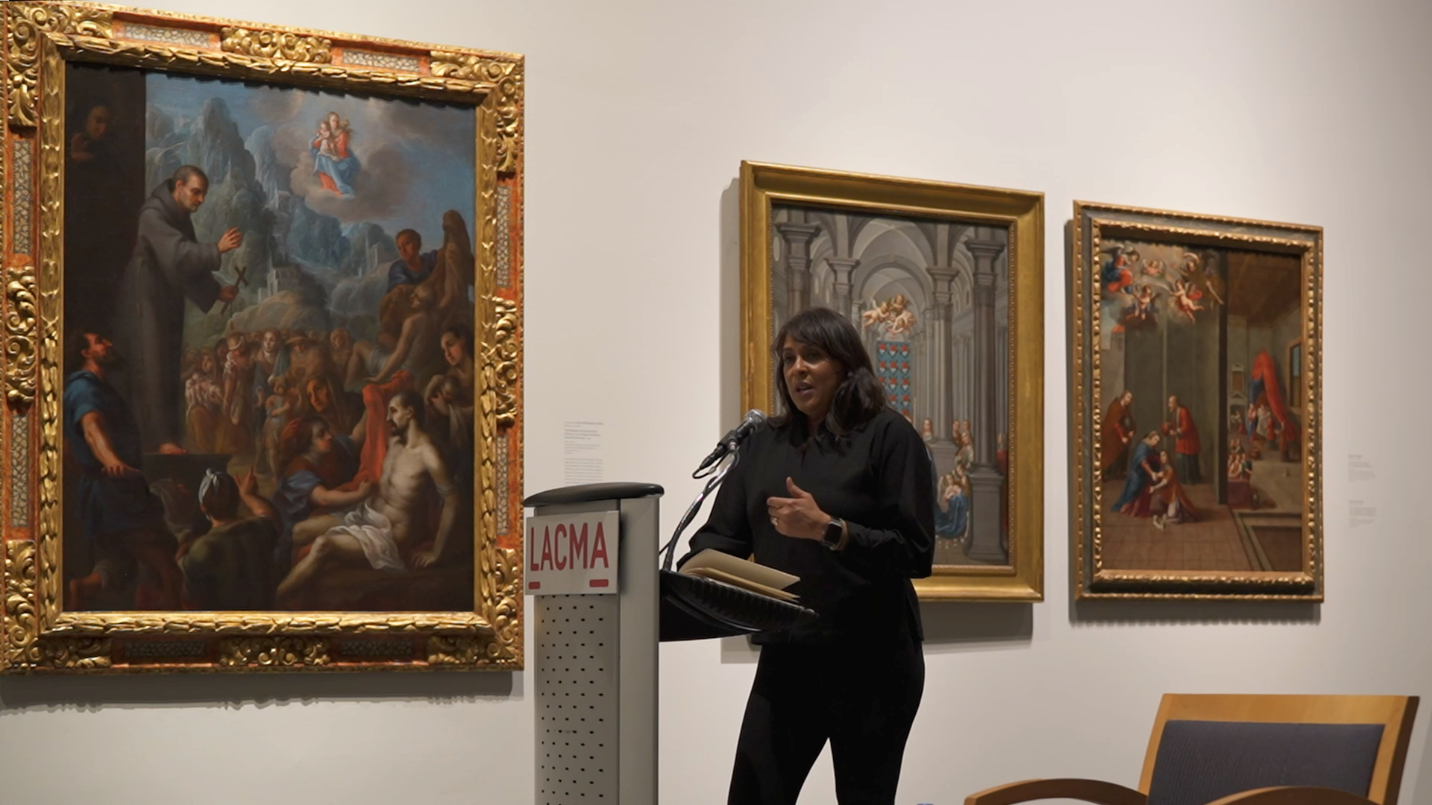

The Latin phrase “ut picture poesis” means “as in painting so in poetry.” On October 12, 2022 Pulitzer Prize–winning author and Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey offered a stirring reading from her powerful and beautifully crafted book Thrall (2012) in response to the casta paintings in LACMA’s exhibition Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800. It was an exceptional occasion to hear her ekphrastic poems about the paintings (and other related images), and to see them anew through her mind’s eye while being enveloped by the artworks in the exhibition.

Afterwards, my colleague scholar Miguel A. Valerio, from Washington University in St. Louis, and I were privileged to engage in a lively conversation about her work, her process, and how her poetry amplifies the meaning of these complex pictures. The recording of the event is included below (alongside a list of referenced works to help you follow the reading). We hope you’ll enjoy it as much as we did.

Selected readings on casta painting:

Deans-Smith, Susan. “Creating the Colonial Subject: Casta Paintings, Collectors, and Critics in Eighteenth-Century Mexico and Spain,” Colonial Latin American Review 14, no. 2 (2005): 169–204.

Earle, Rebecca. “The Pleasures of Taxonomy: Casta Painting, Classification, and Colonialism,” The William and Mary Quarterly 73, no 3 (2016): 437–66.

Katzew, Ilona, ed. New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America. Exh. cat. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery, 1996.

Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004 (reprint 2005).

Katzew, Ilona. “White or Black?: Albinism and Spotted Blacks in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World.” In Envisioning Others: Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America, edited by Pamela A. Patton. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2016, 142–86.

Katzew, Ilona, ed. Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex; New York: DelMonico Books / Prestel, 2017, 276–307.

Katzew, Ilona, ed. Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: DelMonico Books/D.A.P., 2022, 186–200.

Martínez, María Elena. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.