In the autumn of 1951, a clamor erupted in the Computing Machine Laboratory at Manchester University. Inside the lab, a crew from the BBC Children’s Hour radio program gathered around a hulking metal unit that housed endless switches wired to rows of cabinets of cathode-ray tubes. With microphones at the ready, the computer was fired up and screeched out a well-known melody through its loudspeaker, also known as the “hooter.” As each mechanically mangled note of “God Save the King” was etched for posterity into the grooves of an acetate disc, an unidentified woman’s voice muttered “the machine resented it,” and later, when the computer fizzled out midway through Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood,” she slyly commented, “the machine’s obviously not in the mood.” Good-humored ribbing aside, everyone assembled must have been awestruck by the potential of what they’d witnessed.

This was the first ever audio recording of computer music, and the temperamental machine in question was the Ferranti Mark 1, designed by Alan Turing, the visionary British engineer whose electromechanical codebreaking devices gave the Allies an edge over the Nazis in World War II. Turing himself recounted the computer’s audible output as “something between a tap, a click, and a thump,” and he wasn’t alone in acknowledging the noisy nature of these primitive digital utterances. Computer music pioneers resoundingly admitted that the bleeping squawks and shrill belches of their early experiments were far from pretty, but they persevered nonetheless, separating the racket from the potential—edging ever closer to bringing their aural aspirations into existence through the advancement of technology.

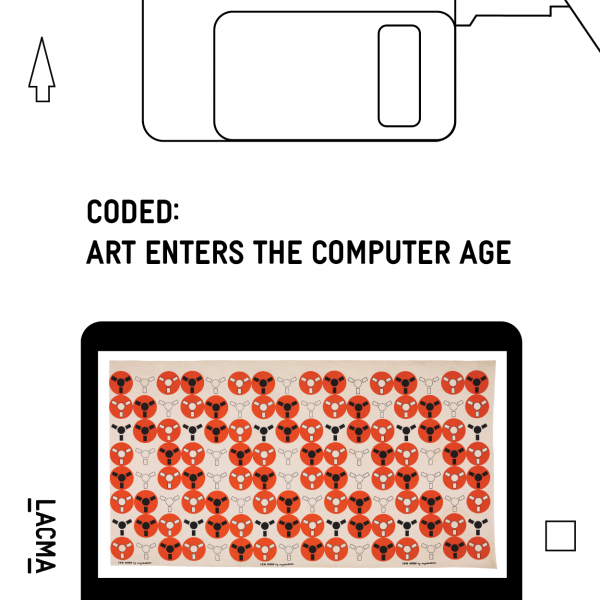

The tracks we chose to accompany Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982 trace the evolution of computer music, including the earliest attempts to nudge these machines into audible action, such as Lejaren Hiller’s Illiac Suite for String Quartet, the first piece fully composed by a computer.

Lofty experiments in analog-digital interplay followed, including Joel Chadabe’s “Settings for Spirituals,” which expanded on the emotional potency of Irene Oliver’s vocals through a program mirroring her nuanced delivery, as well as sounds supercharged by the marriage of fantasy and commerce, such as the Pac-Man theme, a digital melody that dominated video game arcades in the early 1980s and bored its way into popular consciousness.

We have also included works that were not made on a computer at all, yet mimic their function and aesthetic, such as Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Activities for Orchestra, a score for Merce Cunningham’s dance Scramble that revels in indeterminacy like a program freed from its code to seek ecstatic sentience.

The history of computer music is undisputedly male-dominated, in large part because of gender barriers that existed within the institutions where most of the early experiments were taking place, but in the Coded exhibition soundtrack we’ve tried to illuminate the accomplishments of some of the women whose contributions were vital to the field. Much like in the broader field of electronic music, where composer Éliane Radigue created sounds for the musique concrète revolutions of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry or Delia Derbyshire and Daphne Oram crafted ubiquitous, futuristic themes for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, women’s input to the early stages of computer music often went uncredited—but in reality, they were integral from the very first tone.

Betty Snyder Holberton created the world’s first computer song, spending sleepless hours in a Philadelphia lab programming the BINAC (Binary Automatic Computer) to play “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” during the celebration of its unveiling in August 1949—a year before Australia’s CSIRAC (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Automatic Computer) cranked out the “Colonel Bogey March” and two years before the Ferranti Mark 1 became the first computer whose music was recorded.

By highlighting the contributions of the women who helped progress computer music we hope to encourage more future inclusivity.

Computer sounds are inextricable from our contemporary audible environment, but it’s our humanity that enlivens them. One can only hope that the aspiration for creative progress not only fulfills the potential of the tools at our disposal but also leaps beyond the realm of existing technology, propelling us into the next dimension of sonic actualization.

The Coded exhibition soundtrack is now available to listen on MixCloud or Spotify. The exhibition is on view at LACMA through July 2, 2023.