Two exhibitions currently in Los Angeles feature highlights from LACMA’s collection that examine the role of graphic arts in identifying injustice, promoting change, and rallying action. On view at Charles White Elementary School, Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany considers the shared visual strategies that resulted from artists responding to the revolutionary contexts of Mexico and Germany in the first half of the 20th century. What Would You Say?: Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which is on view through June 24 at Vincent Price Art Museum as part of the Local Access partnership, explores how California artists and designers used their work to champion civil rights, oppose wars and oppression, and press for change from the 1960s through the present. While the artists in both exhibitions responded to their own distinct social and political situations, common threads emerge—such as the visual legacy of celebrated Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913).

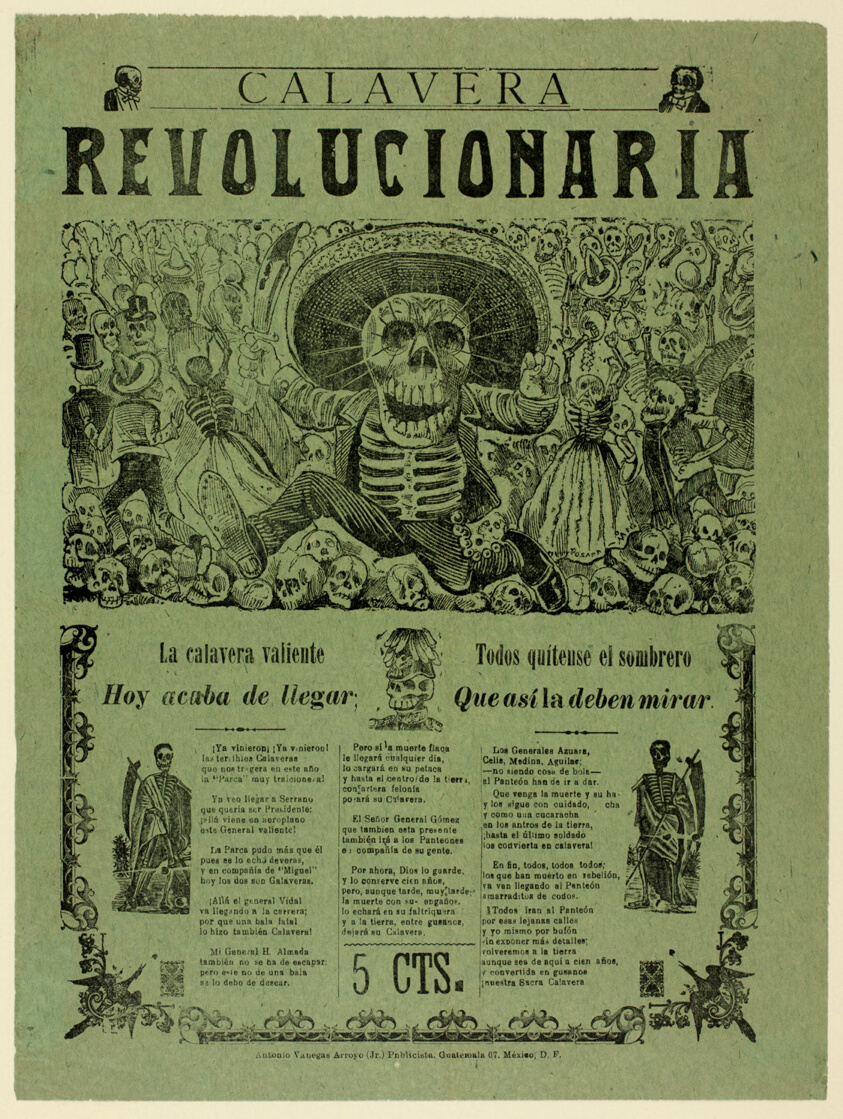

Posada died in 1913, unaware of the fame and renown his work would later garner. Posada is best known for the mass-distributed broadsides he illustrated for commercial publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, in which he portrayed sensational current events, popular stories, and calaveras, the satirical skeletons with which he is closely associated. The widespread access to and appeal of Posada’s broadsides helped cement him as a leading model for artists in Mexico and the United States from the decades following his death to today. French-born artist Jean Charlot is credited with Posada’s “rediscovery.” Writing about the artist in 1925, Charlot described his prints as “genuinely Mexican” and initiated interest in Posada’s work by post-revolutionary artists. Five years later, Diego Rivera declared Posada to be a “broadside warrior” (guerrillero de hojas volantes), enhancing the idea of Posada as a revolutionary artist which many followers embraced.

In 1937 a group of leftist artists founded the Taller the Gráfica Popular (TGP; People’s Print Workshop) in Mexico City, a collective workshop that produced prints to advance changes fostered by the Mexican Revolution. Members of the TGP consciously positioned themselves as heirs to Posada, and as the graphic voice of the Mexican people. When the TGP founded its own publishing house in 1942, its first publication was an album of Posada’s prints, establishing a direct lineage. Furthermore, members of the TGP collaborated to produce calavera broadsides each year to commemorate the Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Following the model made popular by Posada, the TGP artists illustrated current events—both mundane and sensational—with calaveras, using humor to draw attention to difficult realities.

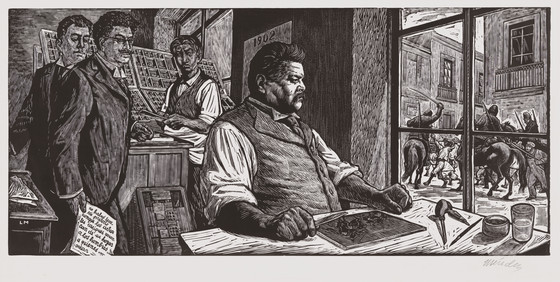

In A Portrait of Posada in His Workshop (Homage to Posada), Leopoldo Méndez—one of the TGP’s founders—imagined a scene in which Posada sits at his worktable, rendering the violent events outside onto the printing block in front of him, surrounded by the tools of his trade. The street skirmish he sees relates to an actual print Posada published in the periodical Gaceta Callejera in 1892, yet the date on the workshop’s calendar reads 1902—the year of Méndez’s birth and a way for the artist to inscribe himself into the scene while honoring Posada. Two other men stand in the back; the figure in front is activist publisher Ricardo Flores Magón, identified by his distinctive glasses, curls, and bushy mustache. In this homage, Méndez has positioned Posada as an unwitting leader in political thinking and image making, and as a role model for Méndez himself, the TGP, and future generations of artists. In Pressing Politics, Méndez’s portrait of Posada is likewise placed at the start of the exhibition, engaged in the act of printmaking and looking out over the artists and artworks that follow.

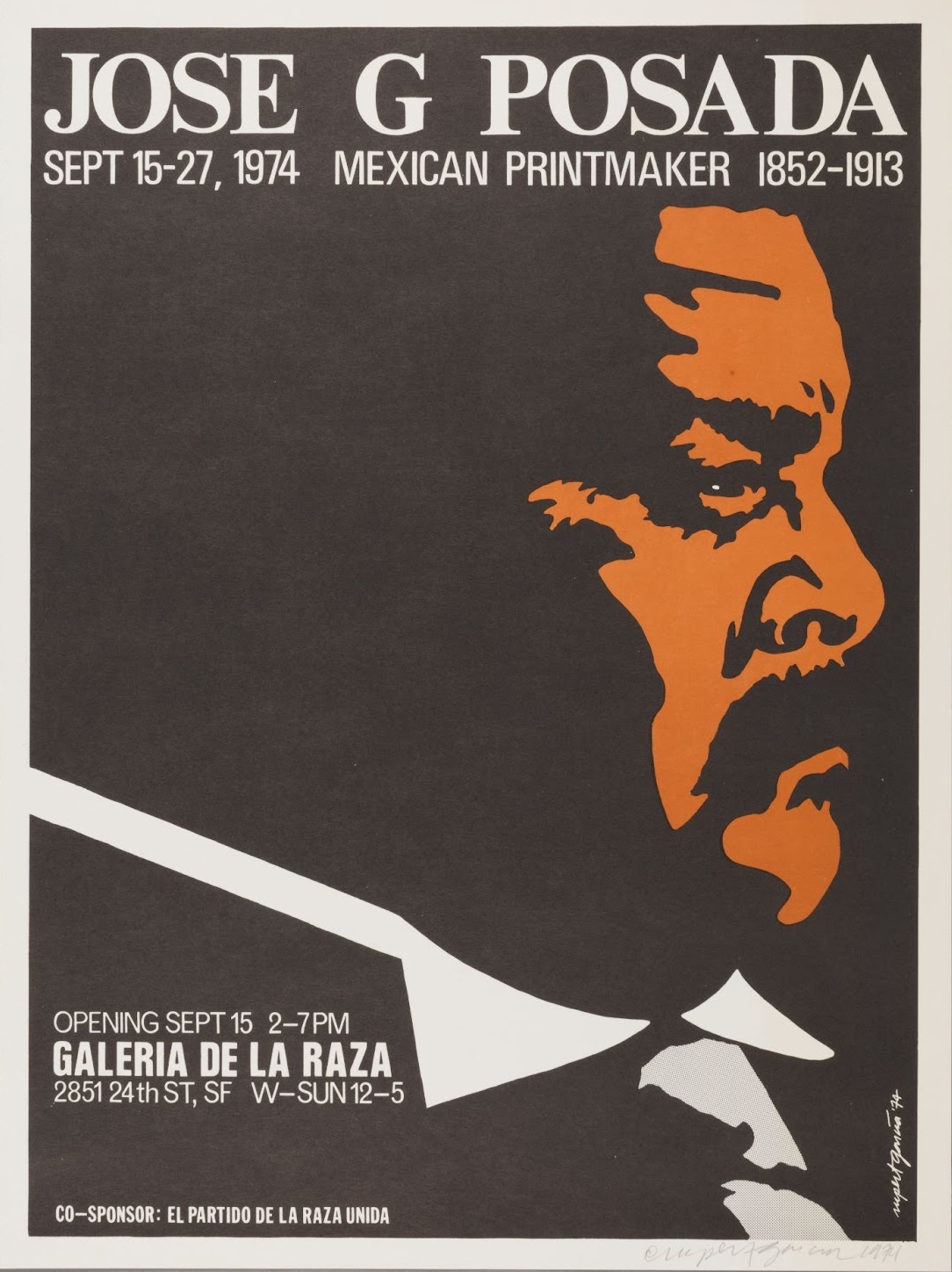

Decades later, Chicano artists and activists also turned to Posada, adopting earlier generations’ portrayal of the influential illustrator as a revolutionary artist of the people. Drawn to his images of Mexican culture as well as his sharp depictions of social class, artists like Andrew Zermeño, whose political cartoons appeared in the United Farm Workers newspaper, and the Sacramento-based collective Royal Chicano Air Force, paid homage to Posada’s distinctive imagery and even reproduced elements of his prints. Rupert García’s dramatic portrait poster advertises a 1974 exhibition of Posada’s work at San Francisco’s Galería de la Raza, one of several key exhibitions that helped introduce the prints to the Chicano community. Community art spaces like the Galería presented the work of Latinx artists that were largely ignored by the dominant institutions, providing inspiration for movement artists.

Other political artists also took note of his work. Artist Robbie Conal, who has earned national notoriety for his instantly recognizable street posters, recalls seeing Posada prints in a museum when he was growing up in New York. The earlier artist’s satirical style was a formative influence on Conal’s own lampoons of public figures. In this poster, he dresses a Posada-like calavera in the pinstriped suit of a Reagan-era politician, calling attention to the rampant corruption in the interrelated illegal covert operations that became known as the Iran-Contra affair.

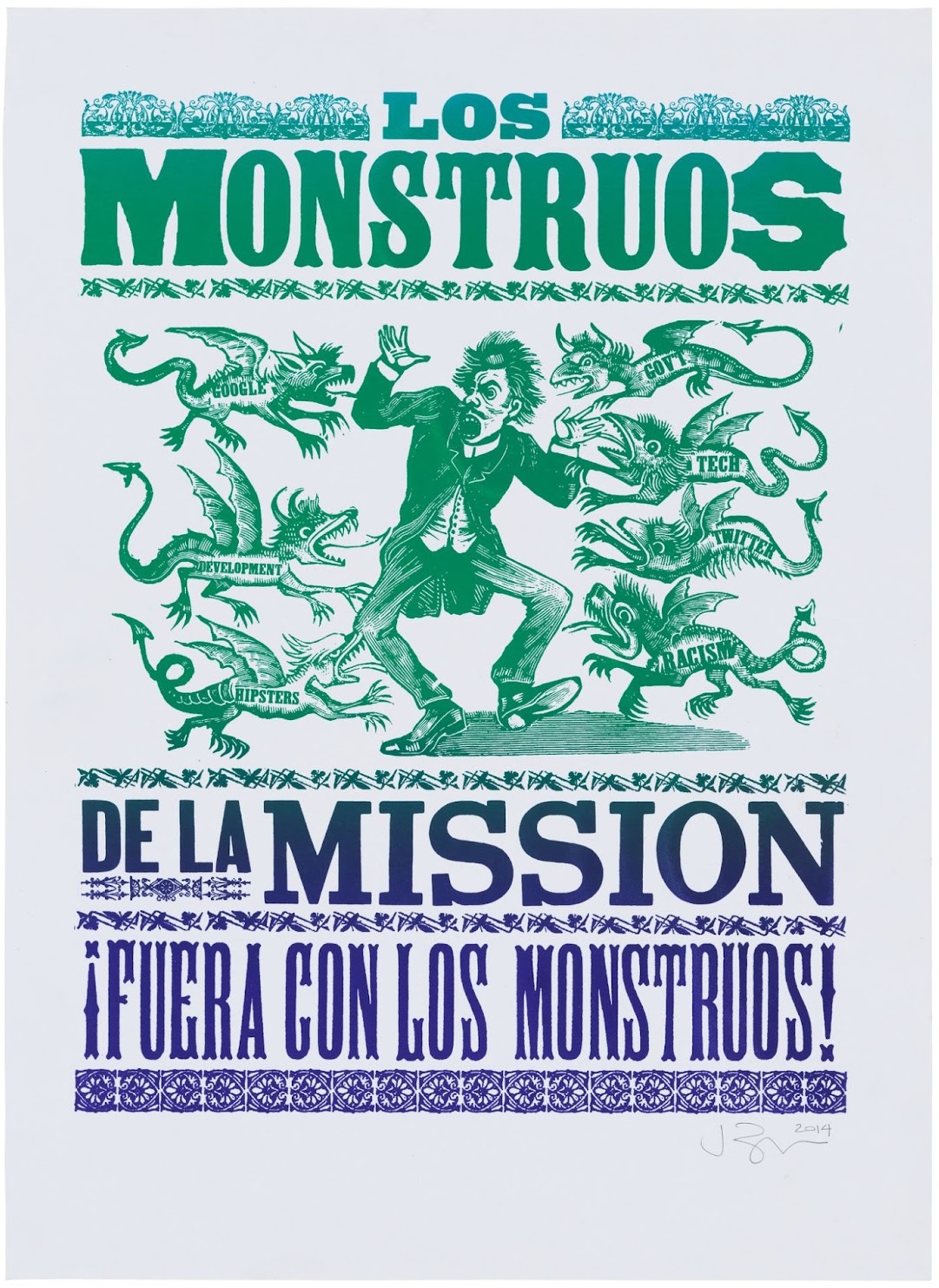

Posada’s now-iconic imagery remains salient for many contemporary activist artists, who incorporated his illustrations into their own protests against anti-immigrant policies, the displacement of communities of color, and other injustices. Jesus Barraza of Dignidad Rebelde describes how Posada’s imagery has become ubiquitous, even though many are unaware of the artist’s complex history. For his own work and research, he has delved into the complexities of Posada’s legacy while still retaining his respect for the artist’s prolific output, stinging critiques of authority, and ability to create images that truly connected with mass audiences. In Los Monstruos de la Mission, Dignidad Rebelde adapts Posada’s Los siete vicios (Los siete pecados capitales) (Seven Deadly Sins) to call out the forces driving gentrification in San Francisco's historically Latinx Mission District. His bold, embellished typography references the wooden typefaces that were popular in Posada’s era.

Together, these two exhibitions demonstrate how Posada’s work has been understood, disseminated, and revered by artists in the 110 years since his death. While his own political views remain a point of debate, his impact is undisputed, as it continues to inspire artists and help their voice their own social critiques.

What Would You Say?: Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is on view at the Vincent Price Art Museum through June 24. Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany is on view Saturdays from 1–4 pm at Charles White Elementary School through July 22. Portions of this text are excerpted from the Pressing Politics exhibition catalogue, available at the LACMA Store.