To commemorate Pride Month, we’re sharing highlights from LACMA’s permanent collection, selected by staff members. The museum’s encyclopedic collection contains numerous stories from the LGBTQ+ past and present—some hidden, some out and proud—and the pieces below and their accompanying reflections are only a few perspectives on queer identity, history, and connections to art and culture.

Holly M., Director of Adult Public Programs

Ay-O, Rainbow Heart, 1965–67

In 1978, when Harvey Milk called for a symbol of unity, artist Gilbert Baker answered with the first rainbow flag. As long as I can remember, Pride events haven't been complete without its vibrant presence. As a kid, chasing rainbows filled me with endless wonder, a feeling that still stops me in my tracks today, making me reach for my camera to capture the magic.

The universal appeal of rainbows shines through in the work of Fluxus artist Ay-O, aka the "Rainbow Man." His colorful creations seem to vibrate up close, reminding me of the lively energy of queer spaces like clubs and festivals, where we've found solace, revolution, and self-expression.

For me, the heart shape holds deeper meaning than just love. It symbolizes the struggles and triumphs of LGBTQ+ individuals and those who came before us, whose presence spans throughout history. It serves as a powerful reminder of the resilience and vibrancy within the queer community, which I've witnessed firsthand. Much like the endless arch of a rainbow, our identities and experiences are vast and everlasting.

Lara Schilling, Content Specialist for Teacher Programs

Alexander McQueen, Woman's Ensemble, 2002–03, and Woman’s Boots, 2006–07

Lee Alexander McQueen was one of the first fashion designers I really fell in love with as a teen obsessed with high fashion and Vogue magazine. I loved his whimsy, his darkness, and the sense that, through his clothing (if only I could afford it), I could transmute into a supernatural, cosmic being.

This was all before I knew I was bi, but wasn’t the writing on the wall? I mean, how can you not gag over the gorgeously queer Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious collection from fall/winter 2002? Tweed, leather, lace-up boots—it was a little bit horse girl, a little bit bondage, a little bit masc.

Did I desire the women who were wearing these concoctions on the runway? Did I want to strut around in these outfits and be desired by potential suitors of all genders? Or did I maybe even want to dress someone else up in them? Was McQueen’s collection a utopian vision of a sartorially divine queendom? Let’s just say, the answer is all of the above. Fashion is inherently queer, dahhh-lings.

To read more about how McQueen's queer identity informed his empowering designs for women’s fashion, check out Lilia Destin's Unframed post.

Arthur Nguyen, Assistant Director, Editorial

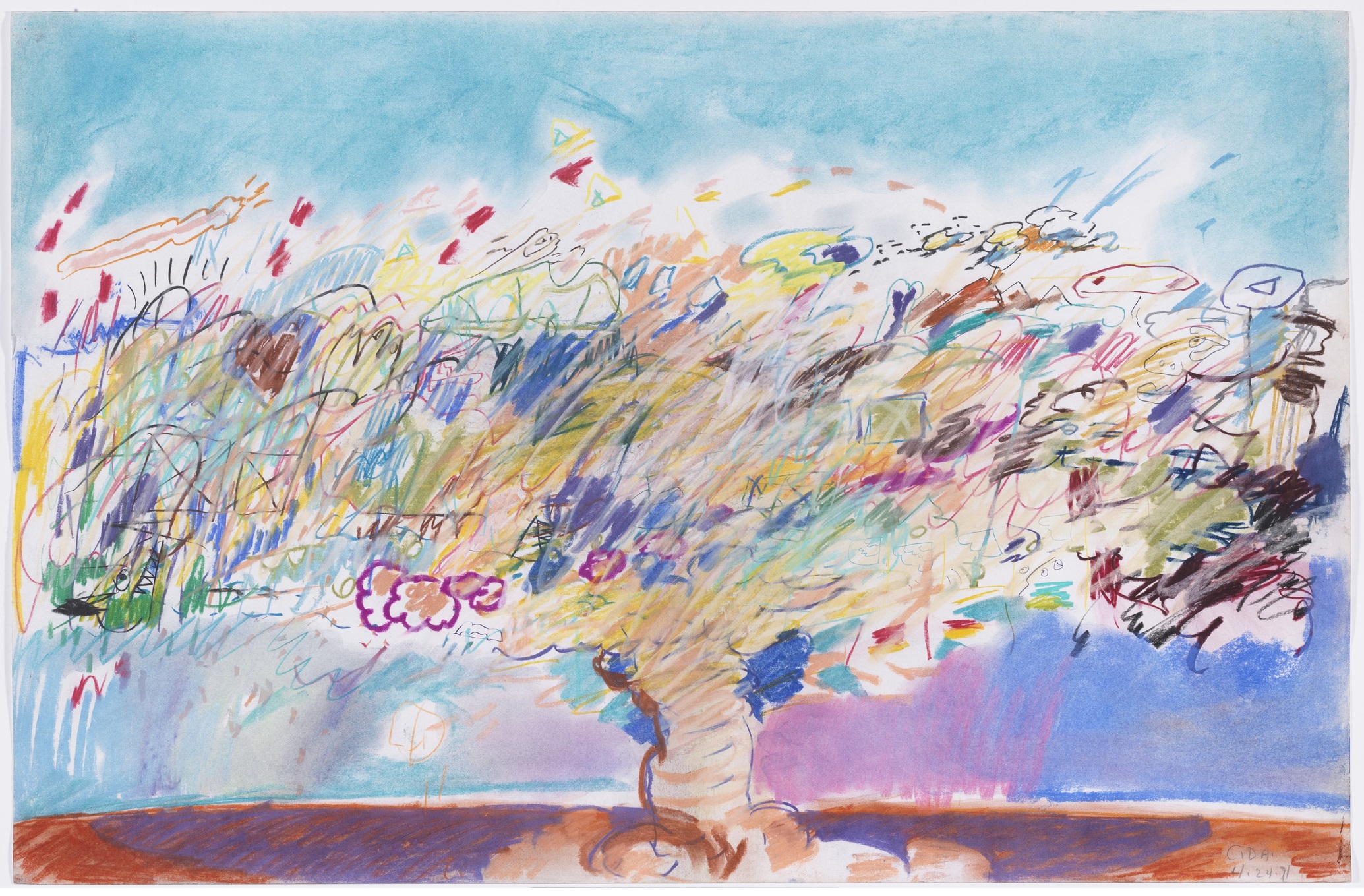

Carlos Almaraz, Tornado, 1971

This pastel drawing by Carlos Almaraz lives up to its title. A narrow funnel at ground level sends an expansive spiral of riotous color into the sky, pushing against the edges of the sheet. Look closer, and you can discern a seemingly random, playful iconography—hearts, clouds, a fanged animal head. Incongruous marks and shapes swirl together chaotically, and beautifully.

This restless energy infuses much of Almaraz’s work, including his streetscapes of Los Angeles and his well-known paintings of fiery car crashes. His career itself never settled in one place. While he was a committed activist in the Chicano movement and a founder of the artist collective Los Four in the 1970s, Almaraz refused to limit himself as solely a social and political artist. He later moved his practice from public spaces to the studio, where he produced deeply personal, introspective works until the end of his life in 1989.

Almaraz’s identity and life experience couldn’t be neatly boxed in, either. His love and generosity spilled into a multitude of communities, cultures, and relationships.

Curator Howard N. Fox, who organized LACMA’s 2017 retrospective Playing with Fire: Paintings by Carlos Almaraz, writes that the artist “was a true mythologist, ultimately believing not in the primacy or the uniqueness of any particular group but rather in the universality of the human imagination.”

Tornado embodies one of the LGBTQ+ community’s most winning qualities: it welcomes people on their own terms, with all of their incongruities. It honors the act of imagination it takes to reconcile overlapping and conflicting identities. Like Almaraz’s colorful storm, we carry our chaos with us. It’s beautiful.

Alexander Schneider, Associate Editor

Thomas Eakins, Wrestlers, 1899

With Wrestlers, Eakins brought a queer viewpoint to American painting at a time when the word “homosexual” had barely reached popular discourse. He submitted it as his diploma painting when he joined the National Academy of Design, and I can imagine how at odds it was with the sensibilities of some of the more polite subjects on view, in part because of its mundane nudity and because the athletes themselves were, going by their suntanned necks and hands, working class young men. Although all five faces in the composition are obscured or impossible to read, the man-on-man action is in your face.

Wrestlers is also a far cry from typical depictions of sports, particularly combat sports circa 1899, which usually highlighted strength, muscle, sweat, violence, and triumph. Instead, the scene is quiet and intimate. The two young, slender athletes grapple under gentle lighting and, though they're pinning each other to the ground, there’s a marked lack of aggression. This moment of tenderness doesn't just compel you to see these wrestlers through Eakins' eyes, but also seems to be proposing a softer version of masculinity, homosociality, and kinship.