World War I (1914–18), originally known as the Great War, was not only a globe-spanning war, but the first global media war. Never before had an event been conveyed to the public in such an immersive way, with a burgeoning mediascape of illustrated newspapers, photography, advertising, and the rapidly advancing medium of cinema, a mass spectacle explored in the exhibition Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media (on view through July 7).

Perhaps no pieces of media from World War I remain as iconic as some of its most prolific propaganda posters: James Montgomery Flagg’s Uncle Sam (above), which was based on Alfred Leete’s popular image of British Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener, for example, is immediately recognizable to anyone in the U.S. today. Not only were such posters designed to catch attention and communicate with limited text and strong graphics, contributing to this cultural longevity, but they had other advantages too: they were relatively cheap to produce, had been tried and tested, and were a medium accepted and understood by the masses. Specific messages were largely dictated by the course of the war, but some major themes seen on many of them included the call to arms, requests for war loans, encouragement of industrial activity, explanations of national policies, channeling of emotions, urges to conserve resources, and informing the public of food and fuel substitutes—often with a large dose of cultural chauvinism.

Below, discover a few of the poster highlights on view in Imagined Fronts, exemplifying just some of the myriad messages, styles, geographic regions involved in the war.

Women munitions workers played a vital role in the war effort; the work was physically exhausting and dangerous, as explosions were frequent and chemical poisoning was a constant threat. The YWCA, the oldest women's organization in the U.S., advocated for gender equality and provided relief services.

Renesch’s broadsides were widely distributed and targeted to various audiences; this portrayal of an African American couple, for example, echoes a similar Renesch composition (titled Duty Calls) that featured a white soldier departing from his sweetheart. While created and distributed by white publishers, messages such as this one appealed to Black Americans seeking full citizenship and representation in an era of segregation.

This U.S. Navy recruitment poster promotes camaraderie among sailors from Allied nations (from left to right: Japan, France, United States, Britain, Russia, and Italy).

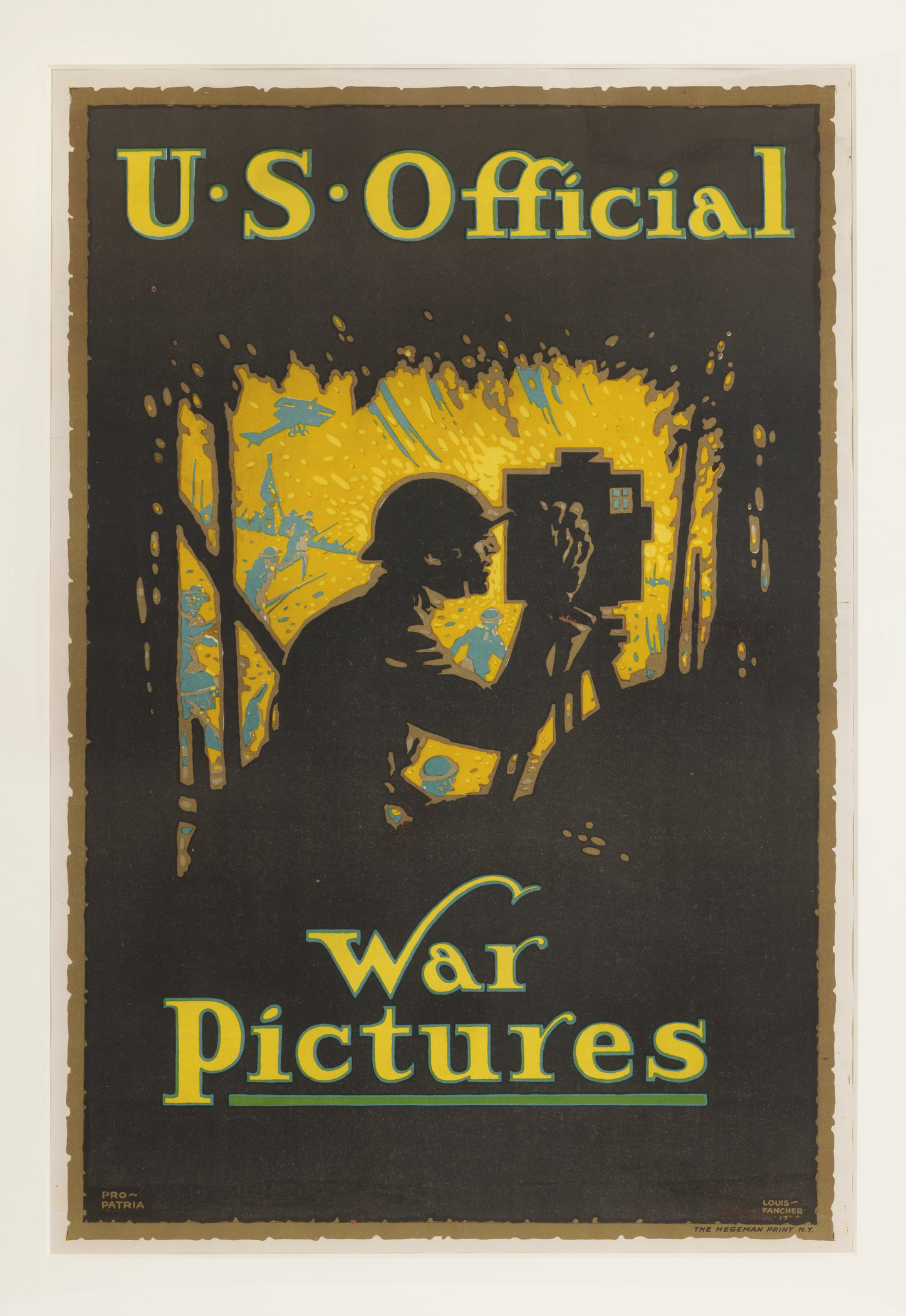

The U.S. Army Signal Corps provided footage for films that were part of the massive propaganda campaign spearheaded by the Committee on Public Information. Most footage, however, was not made at close proximity to battles, as is suggested here by the soldier filming against a backdrop of explosions.

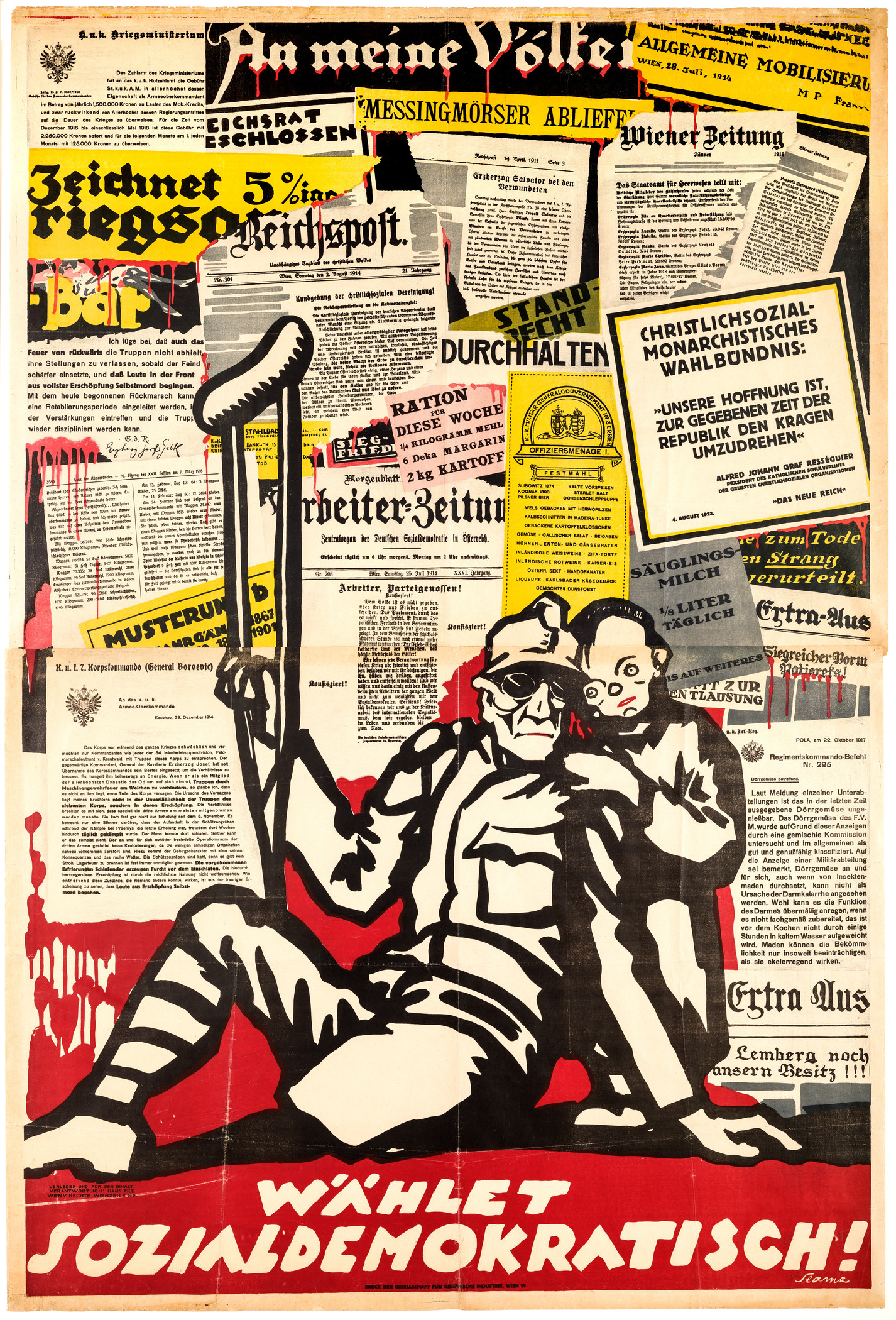

Slama’s poster for the Austrian Social Democratic Party reproduces documents related to the terrible conditions of the war, thereby promoting the Social Democrats as a political alternative to those who had supported it. The many texts include a weekly ration card (allowing just 1/4 kilogram of flour, 2 kilograms of potatoes, and 60 grams of margarine) juxtaposed with a dinner menu for officers (who enjoyed such delicacies as cold sturgeon, roast duck, ice cream, and “hand grenade cocktails”).

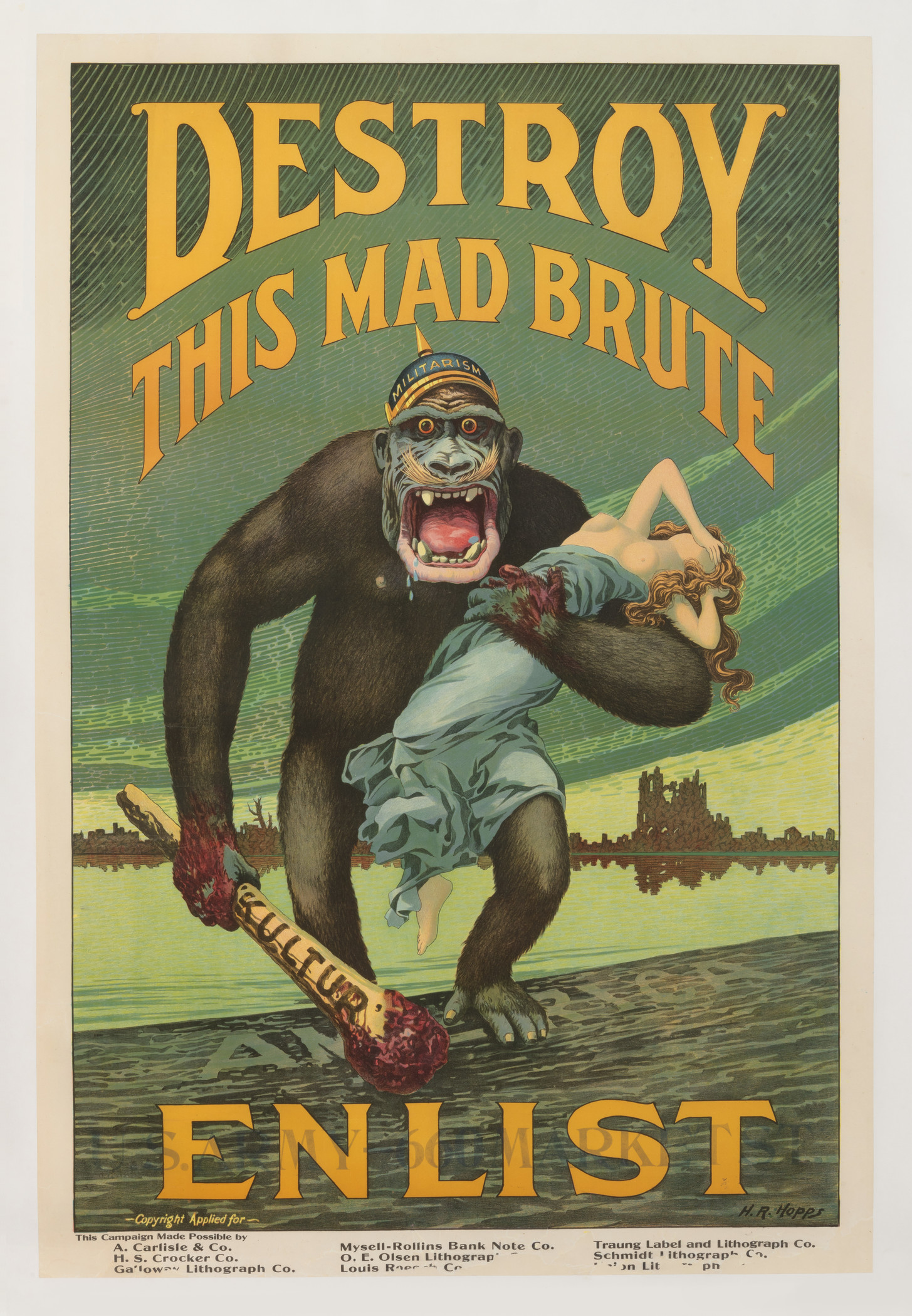

Images of Germans as bestial “Huns” committing atrocities proliferated in Allied propaganda. Here, the “mad brute” wields a bloody club labeled Kultur, in reference to Germany’s invocation of its cultural superiority as justification for its war aims.

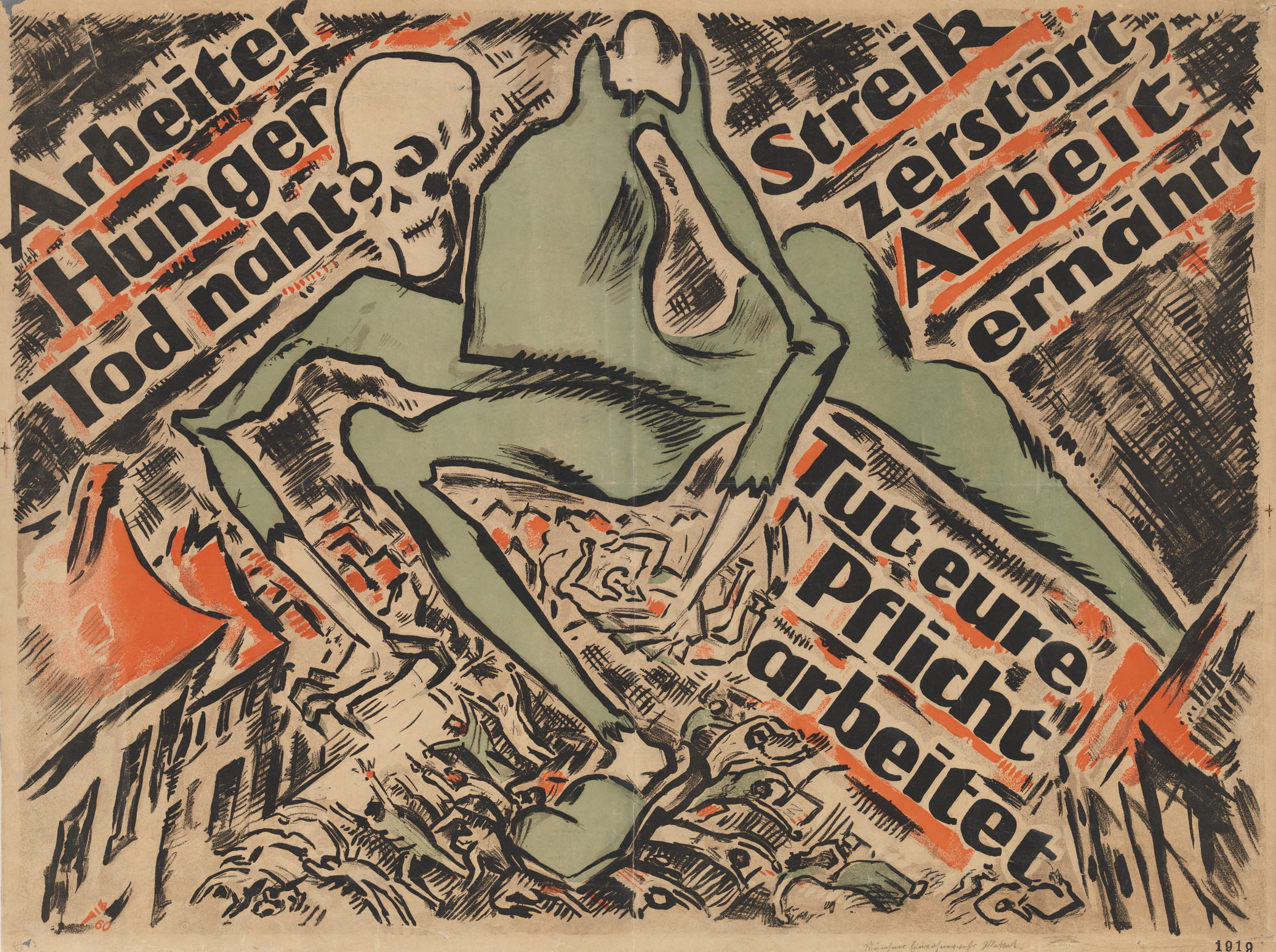

During the postwar social unrest in Germany, the provisional government’s Publicity Office (previously a military department) attempted to quell strike actions by commissioning artists to create propaganda posters in a revolutionary style.

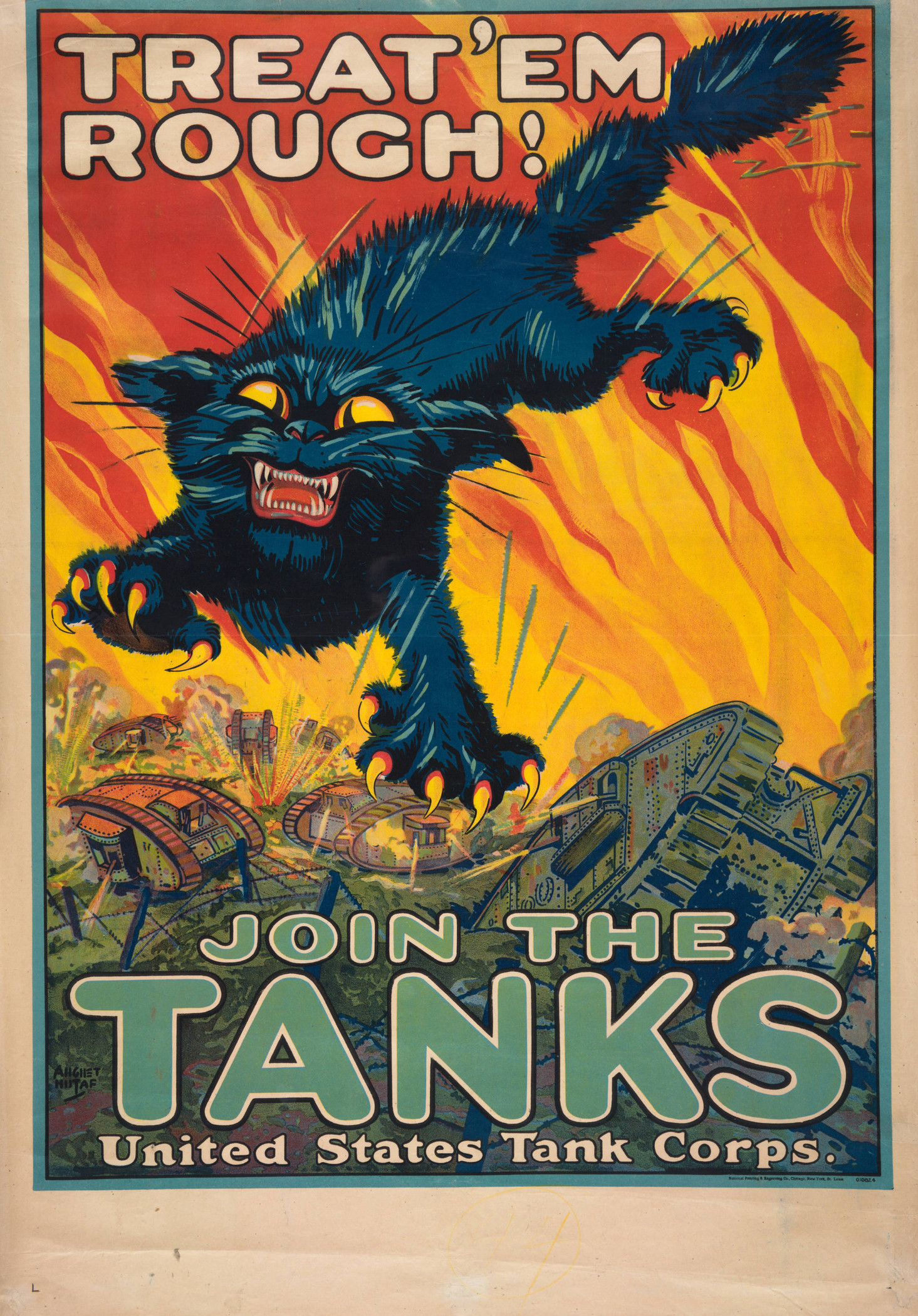

Tanks were hailed in the Great War for their power, invulnerability to bullets, and ability to break through barbed wire and enemy trenches, even if in reality they were unreliable and easily disabled by artillery.

See these posters and more of the art and media of World War I now in Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media, on view in the Resnick Pavilion through Sunday, July 7, 2024.