Kristina Wong is a Pulitzer Prize Finalist in Drama, Guggenheim Fellow, and Doris Duke Artist whose newest performance addressing food insecurity will premiere at ASU Gammage in April 2025. Here, she reflects on her recent work with the World Harvest Food Bank ahead of our upcoming panel discussion Food for Thought: Combating Food Insecurity in Los Angeles on Thursday, July 25, which will explore systemic food insecurity in L.A. and how local artists and organizers are fighting for change, presented in conjunction with the exhibition Dining with the Sultan: The Fine Art of Feasting.

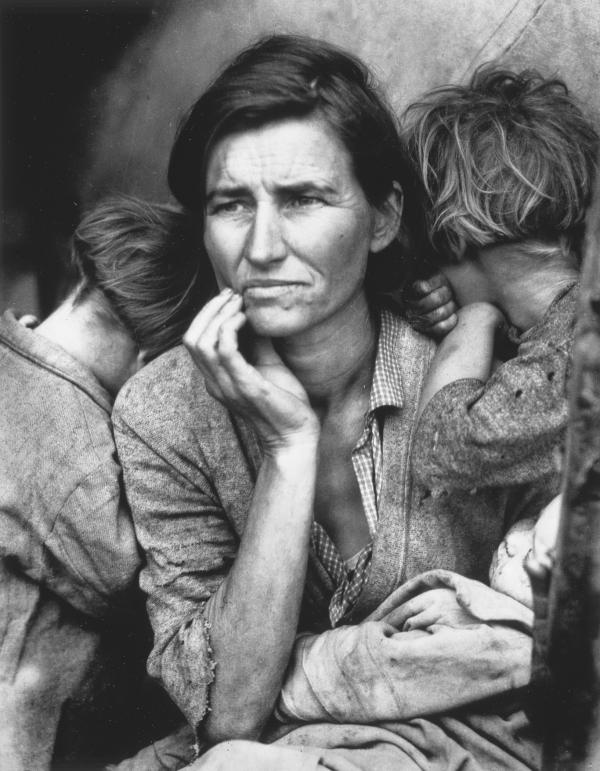

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother is one of the most iconic photographs of hunger in history. Unfortunately, this Great Depression–era image is also cemented in our heads as what food insecurity looks like, but food insecurity isn’t just the stuff of the Dust Bowl: in the U.S. today, it affects, among others, college students, the working poor, and, recently, more middle class families who can’t keep up with the rising costs of living. In my life, food insecurity has meant playing “bill paying whack-a-mole”—prioritizing rent over groceries, and choosing unhealthier, cheaper, more filling food.

I’m not Dorothea Lange but I am a self-proclaimed “food bank influencer” who makes haul videos for World Harvest Food Bank, located just southwest of my Koreatown home, in Arlington Heights. Since 2019, I’ve been obsessively looking at small and large emergency food systems around the country and noticing how “temporary” measures have become very permanent. I’ve been reflecting on how modern food insecurity has shaped my own communities and studied actionable (though not simple) steps to get us beyond band-aiding hunger with canned food drives. All this informs a new stage show called Kristina Wong, #FoodBankInfluencer that will premiere in April 2025.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I found myself at the convergence of art and activism (sometimes referred to as “social practice”) when I became the unwitting leader of the Auntie Sewing Squad, a loose mutual aid collective of 800 volunteers who organized, sewed, and distributed home-sewn face masks to America’s most vulnerable communities. Suddenly, a sewing hobbyist with scrappy guerilla organizing skills (me!) felt like the difference between life or death for our fellow Americans. ASS (our unintentional acronym) was supposed to be a two-week stop gap, but our work continued with coat drives, food aid, and buying an ambulance for Standing Rock across the first 500 days of the pandemic.

World Harvest Food Bank ended up being a huge part of our ASS ecosystem. Founded by Glen Curado, I consider them a disruptor in the emergency food space. Rather than requiring proof of income and handing out food that people might not eat, they allow anyone, rich or poor, to come in and “shop their donations”—offering the dignity of choice. A $50 donation buys a large cart of food, or you can volunteer in exchange for groceries. Because World Harvest’s model doesn’t restrict who they distribute food to, ASS was able to quickly reroute their food to the same communities receiving our masks: asylum seekers, Indigenous communities, and farmworkers.

When I found World Harvest, I ceased to have a personality aside from talking about this food bank and how they took the stigma out of eating from one. I started shooting influencer videos for my YouTube channel, playing up the performance of excess in the least rich of imaginable places. It’s when I become obsessed with something that I know it’s time to make it into a show. Kristina Wong, #FoodBankInfluencer was a natural extension of my past work in connecting community to art. Sharing with my audiences all the ways in which food insecurity ties itself into the communities I live in through my artistic practice.

Now I can’t unsee the presence of emergency food systems, especially in my neighborhood, from abandoned baggies of “free school lunch” carrots overflowing in trash cans to picked-over contents of abandoned food bank boxes re-donated to World Harvest or left on the streets for others to forage through. While emergency food systems are imperfect, they are crucial, especially in Koreatown where the median household income is $51,013 per year. For reference, a family of two working adults with two children in Los Angeles need a salary of $276,557 to “live comfortably.”

What I want my new work to do is to actually incite real systemic change. In a dream world, this food bank I love so much would close down because everyone has what they need to live and don’t need to rely on the charitable sector. I know that’s an ambitious task for art, but I hope that at least people in my audience will say to me: Wow, I don’t want to stop at just giving to food drives, I want to overhaul the entire system that keeps people hungry.

Speaking of, my best friend Glen Curado of World Harvest Food bank, along with other local leaders addressing food security, will be speaking at an upcoming panel at LACMA on Thursday, July 25.