It's not every LACMA staffer who is involved in putting together an exhibition and who also finds his face in the show. Such is the case for Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Curatorial Fellow in the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department, and the current exhibition The Sun and Other Stars: Katy Grannan and Charlie White. Unframed’s Stephanie Sykes walked through the exhibition with Ryan to discuss what the inclusion of his school portrait means to the exhibition.

Installation view, The Sun and Other Stars: Katy Grannan and Charlie White, © Charlie White, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

How did you end up as part of Charlie White’s exhibited research material?

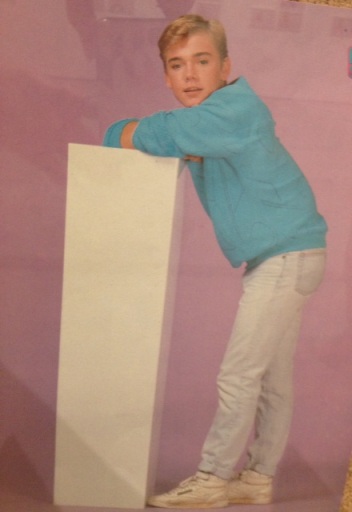

I helped Charlie and his assistant put together this piece, which is a purpose-built installation of teen ephemera, dating from the 1940s through the present day. The images are taken from teen and tween magazines and vintage advertisements that Charlie has collected over the years. Some of it he’d had for decades; some of it he got on eBay; some of it he had his assistant buy that day from Walgreen’s. His intent was to show the production and manufacture of the blonde teenager as a central part of the American mythology of youth.

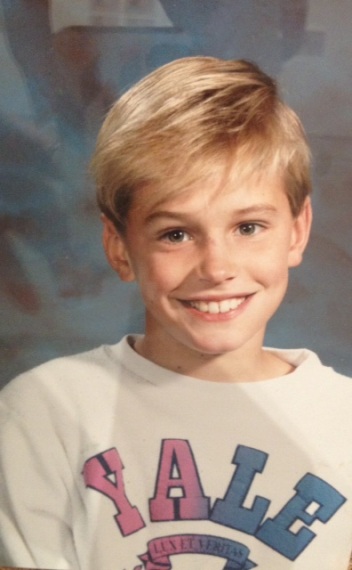

As I was helping him, I was looking at a picture of Ricky Schroder from the mid-1980s and jokingly mentioned that I looked a little bit like him as a child. He laughed and said, “I can imagine,” and asked me to send him a picture. I knew I had this school portrait that was a point of shame and embarrassment for me for a long time, but which now I quite like. I used to fear that my friends would see it because it highlights all the naïve tween vulnerability that I really wanted to dispel in my later teen years. There’s something about those feathered bangs and pink and purple lettering that doesn’t exactly shout masculinity, which is something I worried about as a teenager.

I sent him the image, and he immediately said he wanted to include it. So, there I am.

Ricky

Ryan

How do you feel your image sits amongst the others?

It fits well within the piece. There’s a naïve, blonde, happy quality that I’m exuding that is definitely part of the celebrity culture Charlie captures. A lot of this exhibition plays with the real versus the prosthetic. At what point does the mythology of teen life become reality, and vice versa? This picture is not contrived for public distribution, and I was very much that pink-cheeked child. The fact that I resemble so closely these other produced identities—which are carefully designed and marketed for mass consumption—speaks to the ways in which the manufactured image and the lived reality of a particular type of youth experience is often one and the same, both feeding off of one another.

It’s interesting that this image was in some ways a source of shame for you, yet here it sits in an installation examining the idealized American youth. When you were younger, did you have any concept of your pop culture appeal? Did you realize you were a part of this culture?

I was an avid consumer of all these things. I had an older sister and read all these magazines, so in some way I was absorbing this visual culture.

It’s hard to say if I was aware of my role within the system of pop culture back then. At a certain point in my life, I really wanted to be in the entertainment industry, so yes, I suppose in some way I wanted to be part of it and wanted to look like that. I mean, look how happy I seem!

Installation view, The Sun and Other Stars: Katy Grannan and Charlie White, © Charlie White, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA. Ryan’s photo is in the lower right corner.

The Sun and Other Stars: Katy Grannan and Charlie White fixates on the aspirational. I see that in your picture as well. The Yale sweatshirt reveals a desire to be more than just a pretty face, to show that there’s a brain to go with it.

I grew up in a really small rural town in Oregon with poor public schooling, so the notion that I was going to go to Yale was a big hope and dream. It’s a slightly different aspiration than what’s happening in the exhibition’s other works, which is really more of a desire to be famous or seen or known, but there’s still an element of desire that I think is similar.

Aspiration is a large fixture of Katy Grannan’s section of the exhibition, the idea of hoping against hope that the impossible can be possible. That especially comes to play in her film piece, The Believers.

Now that you’re all grown up and no longer wearing your Yale sweatshirt, whose series of portraits do you relate to more: Katy’s or Charlie’s?

I still have so much pop culture in me. I love teen movies and sugar pop music, but at the same time I have a serious academic side and really appreciate eccentricity. There is something about the uniformity of this celebrity culture that is nauseating and even dangerous, but is also part of its appeal. I think that’s Charlie’s interest—not that he’s celebrating the culture, but examining the power of the recycling of visual tropes. My heart is really with Katy’s subjects in the sense that she’s interested in individuals, and Charlie’s quite the opposite, looking for uniformity and the evacuation of individuality. Seen like this—with all of these blue eyes staring out at you—there’s something even ugly about this kind of unblemished beauty. These kids are part of a machine designed to tell people how they should and shouldn’t look.

Which is literally what Charlie White’s A Life in B Tween discusses: that life is more beautiful when it comes at you through a machine.

Yes, and through a camera, which is a part of the logic in Katy’s contribution to the exhibition. For some people, life is only fulfilling when they’re being photographed. They only exist if someone is there to document them.

That’s certainly true of the woman who plays and lives as Marilyn Monroe (Melissa Weiss). She seems only to truly be herself when she’s in front of the camera, ironically, when she’s performing someone else’s identity.