Robert Mapplethorpe is indelibly a New York artist. His life and career are redolent of the history of New York City at a crucial moment in its art and cultural history—a context so eloquently drawn in Patti Smith’s 2010 bestseller Just Kids. Yet here we are in Los Angeles, a city that Mapplethorpe avowedly disliked, where Mapplethorpe’s archive and much of his life’s work has come to rest—thanks to a joint acquisition by LACMA and the Getty. For all of his ties to the metropolis on the other side of the continent, L.A.’s claim to Mapplethorpe’s legacy is not quite the mismatch it might seem.

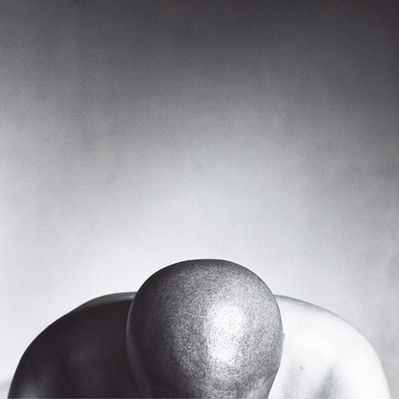

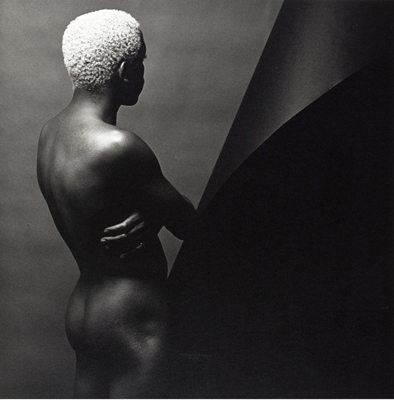

Robert Mapplethorpe, Cedric, N.Y.C. (X Portfolio), 1978, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Cedric, N.Y.C. (X Portfolio), 1978, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

It was in L.A. that one of the first exhibitions of the controversial X Portfolio, featured in the current LACMA exhibition Robert Mapplethorpe: XYZ, was shown at the now-defunct Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA) on Robertson Boulevard. In August of 1978, almost immediately after the thirteen sadomasochistic homoerotic images had been printed and packaged as a portfolio, they were displayed in the small Entrance Gallery at LAICA for a large, diverse, and curious Los Angeles audience. I sat down with Britt Salvesen (curator of photography at LACMA and of the current Mapplethorpe exhibition), Charles Christopher Hill (curator of the LAICA exhibition), and Robert Smith (former director of LAICA) to discuss this historic exhibition. The conversation yielded more than a couple of surprises.

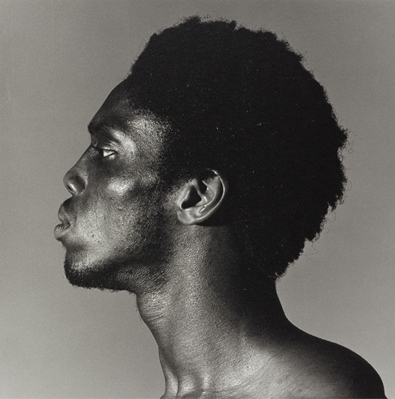

Robert Mapplethorpe, Alistair Butler, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Alistair Butler, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The first surprise was that Hill and Smith had no idea what exactly they were going to be exhibiting when they agreed to do so. The LAICA exhibition of the X Portfolio owed itself largely to San Francisco gallerist Simon Lowinsky, who had exhibited works by Mapplethorpe the previous spring. Hill, an artist in his own right whose work was shown at the Lowinsky Gallery, was offered a set of prints that “would really get a big crowd,” but had little information beyond that. In what is some indication of the quaintly ad hoc nature of curating contemporary art at the time, the prints arrived from the gallery pre-framed, bringing the total cost for LAICA to a jaw-droppingly low price of postage: “The whole exhibition came down, ready to put on the wall, bang, bang, bang.”

Robert Mapplethorpe, X Portfolio, 1978, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, partial purchase with funds provided by The David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, X Portfolio, 1978, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, partial purchase with funds provided by The David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

A testament to the surprises involved in curating before digital image files could be sent conveniently via email, Hill and Smith cracked open the crates upon their arrival to get their first glance of the works they had agreed to exhibit. With telling pith, Hill recalled his response upon seeing the works: “Oh, this is going to be exciting.”

Given the descriptive title Bondage and Discipline, the exhibition ran for one month and attracted, according to Smith, “a different audience” from what typically came to the LAICA exhibitions. Conveniently located on one of the main thoroughfares in West Hollywood, the exhibition attracted a mix of contemporary art enthusiasts and gay sightseers, piqued by the sexual content of the images and the reputation of the artist. Although the curator and director recognized the controversial nature of the imagery, they felt no need (unimaginable in today’s arts institutions) to include warning signage, because at the time “nobody would do something like that.”

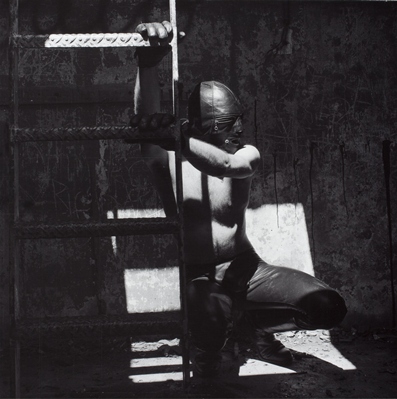

Robert Mapplethorpe, Jim, Sausalito (X Portfolio), 1977, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Jim, Sausalito (X Portfolio), 1977, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

In what would become a familiar story in the history of the X Portfolio, the exhibition stoked controversy and raised issues about funding for contemporary art at LAICA. The problem arose when Marcia Weisman, a longtime supporter of LAICA and an instrumental figure in its founding, came to the galleries accompanied by roughly fifteen students who were participating in her course on art collecting. Although the class passed the Mapplethorpe works on their way in unperturbed, a man who was able to take a closer look in transit to the bathrooms (the gallery was appropriately adjacent), returned to Weisman agitated and concerned. Not one to shy away from contemporary art, Weisman asked the class to join her in a viewing of the works. Though she was generally “pretty much game for anything,” she found the works upsetting and called on Smith to answer for why he featured the portfolio at LAICA and in such a prominent location. Diplomatically stating that “we weren’t being proponents of the activity, that we saw them purely as aesthetic objects,” he soon lost his patience with the interrogation and made the case that a priggish objection to the work expressed an ignorance of human sexuality, even relating the activities taking place in the photographs to the sexual exploration common among teenagers. This latter comment, probably because many of the people in the class had teenage children, “blew the top off of everything.” In response, Weisman took a step back from her involvement with LAICA—in the politic language of Smith, “she didn’t really call for quite a while after that.”

Robert Mapplethorpe, Leigh Lee, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Leigh Lee, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

That would not be the end of Mapplethorpe at LAICA, however, and the artist’s work would be as much the solution as the cause of problems for the institution. Smith organized a fundraiser at, of all places, the Hamilton High School gym, which featured two of Mapplethorpe’s film works, Still Moving and another rarely seen film, Robert Having His Nipple Pierced, directed by Sandy Daley. Hill laughingly recalled that the latter film was “beautifully photographed in color, and a lot of red blood was flowing.” Some sense of the audience at the fundraiser is provided by Smith: “I got up, and I made a statement that something might be shown that was objectionable, so if anybody was worried, I gave them the option to leave. Of course, everybody clapped.” The fact that such a raucous fundraiser using such graphic Mapplethorpe imagery could take place in a public high school gym gives some indication of how far things were from the “Culture Wars” that erupted only a decade later.

The circumstances around this early exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio uncannily anticipated the kinds of responses that would follow the work as it reached a larger and larger audience as the photographer’s star rose. Mapplethorpe’s early history in Los Angeles represents a microcosm of some of the tensions and excitement that his work inspired. It might even be argued that Los Angeles shares much with Mapplethorpe in its progress and maturation. The L.A. art world was much like Mapplethorpe in 1978: inchoate, promising, and vast in its skills and resources but still struggling for acceptance within many sectors of the art establishment. It seems fitting, then, that Mapplethorpe comes to L.A., just at the moment when the city and the artist have established themselves as fixtures in the global art world.

Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Fellow, Wallis Annenberg Photography Department