When I look at the harsh dark shadows, the distorted angles, and the magnified expressions on people’s faces in the exhibition Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema: Caligari and Metropolis, I feel at home. What might be disturbing to other viewers seems to be ingrained as a nostalgic memory in me, as part of the German collective subconscious.

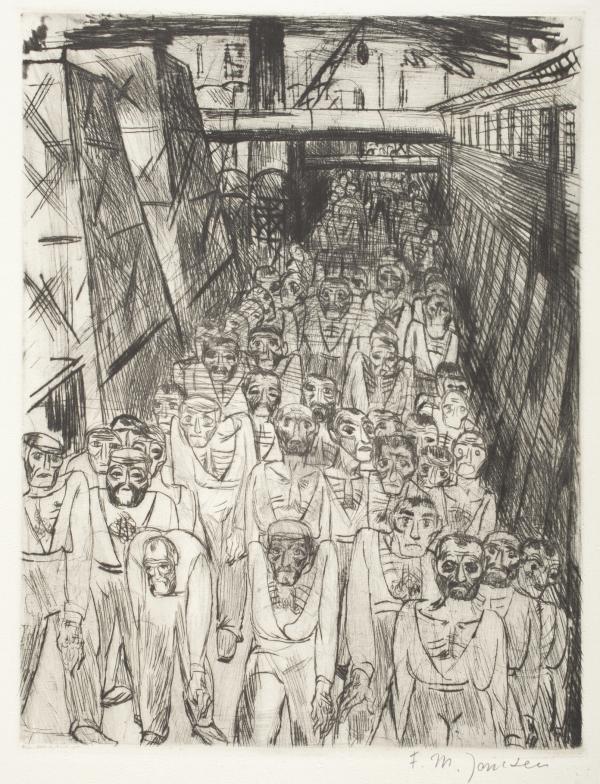

Franz Maria Jansen, Untitled, 1921, from the portfolio Industrie 1920 (Industry 1920), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds

Franz Maria Jansen, Untitled, 1921, from the portfolio Industrie 1920 (Industry 1920), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds

At the turn from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, the role of man (and woman) changed radically with industrialization. Life became more self-determined, structuring powers like the church and the monarchy were gone. But with self-determination came not only freedom but also fear. Accomplishments of modern life were celebrated: electricity, speed, machines, automobiles, and weapons—but at the same time there was fear, which was exponentiated by the outbreak of World War I. The lost war left Germans traumatized. While psychological trauma stayed mostly hidden, the ruins and crippled war veterans were out in the streets for anyone to see.

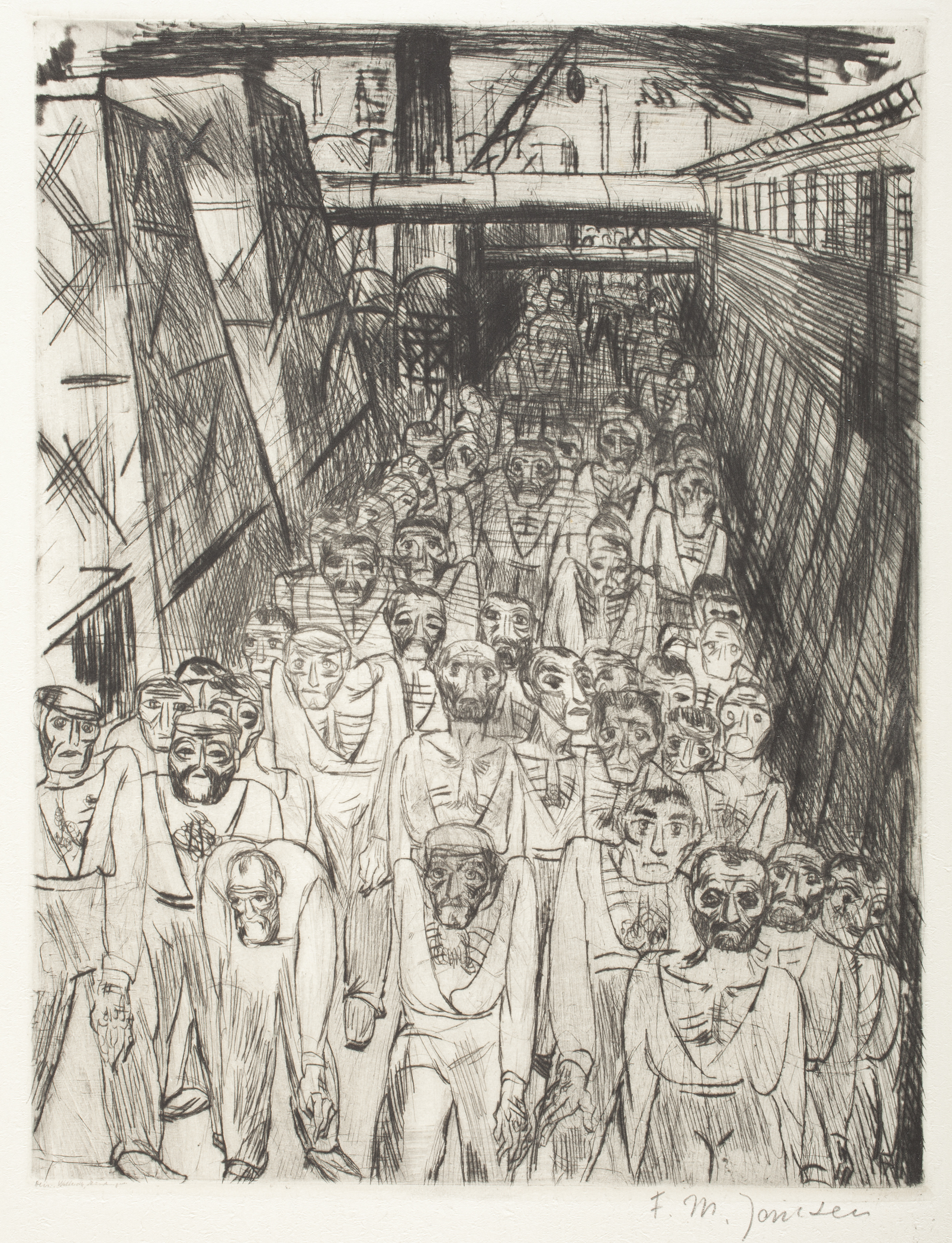

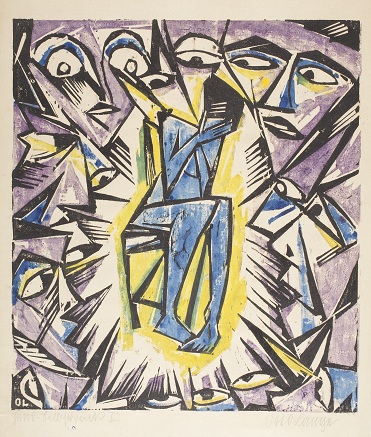

German boxing legend Max Schmeling and other athletes in “Der Querschnitt” (Zeitgeist magazine published by art gallery owner Alfred Flechtheim, LACMA Rifkind archive)

German boxing legend Max Schmeling and other athletes in “Der Querschnitt” (Zeitgeist magazine published by art gallery owner Alfred Flechtheim, LACMA Rifkind archive)

Artistic response to the trauma was split between focusing on the body versus mind; on glorification versus accounts on fear. One artistic stream was to glorify the strength of the wholesome athletic body, the exact opposite to the crippled war veterans in the streets. The idea of the man-machine, made popular by industrialization, was fortified. Artists and intellectuals of the Weimar Republic became fascinated with sports in general, and with boxing in particular—a metaphor for life-or-death struggle. Playwright Berthold Brecht and painter George Grosz paid court to German boxing legend Max Schmeling. Later, under Nazi rule, the idolized athletic body transformed into the soldier’s body. What stood for trauma healing between the wars turned into aggression and new destruction in World War II.

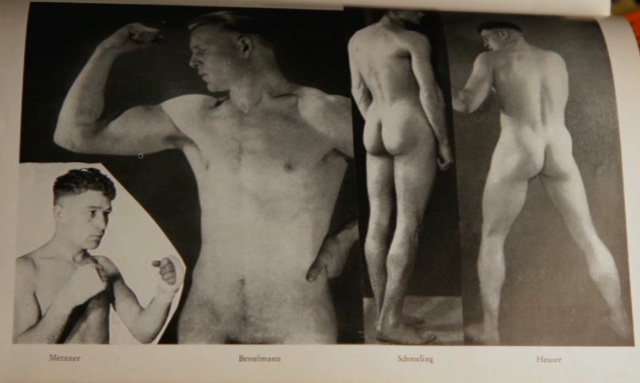

Otto Lange, Vision, probably after 1919, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

Otto Lange, Vision, probably after 1919, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

Another artistic stream centered on the psychological trauma and the unconsciousness. Madness, insanity, and betrayal are topics expressionist films and art explore. The disenfranchised and the troubled souls are portrayed, their fears and pains screaming out loud. Ordinary people lead lives devoid of meaning and damaged by modernity. Their inner worlds are made visible by non-realistic, geometrically absurd cityscapes, by bold contrast of light and shadow, by expressive make-up and acting.

In the films Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari a man-machine (the robot in Metropolis and Cesare in Dr. Caligari), programmed by a self-delusional man of power, brings torment and death to the enslaved and the vulnerable. Put on a pedestal at first, the man-machine is ultimately subdued. Both films reflect the trauma of World War I and may be read as foreshadowing what was to come. Expressionist art was later denounced as degenerate by the National Socialist Party.

Horst von Harbou, Untitled (Robot Maria dancing in night club), 1926, Film still from Fritz Lang's movie Metropolis, purchased with funds provided by the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation

Horst von Harbou, Untitled (Robot Maria dancing in night club), 1926, Film still from Fritz Lang's movie Metropolis, purchased with funds provided by the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation

Fritz Lang as well as many other German artists fled to the U.S. And the expressionist “baggage” they brought influenced American gangster and horror films. Highly stylized set decoration and exaggerated and dramatic lighting are some techniques employed by Orson Wells and Hitchcock to make emotional worlds visible—fear, horror, and pain.

![Unknown German Artist, Untitled (Cesare [Conrad Veidt] Carrying Jane [Lil Dagover] across Rooftops), 1919, set photograph from the film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies](/sites/default/files/attachments/6j.jpg) Unknown German Artist, Untitled (Cesare [Conrad Veidt] Carrying Jane [Lil Dagover] across Rooftops), 1919, set photograph from the film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

Unknown German Artist, Untitled (Cesare [Conrad Veidt] Carrying Jane [Lil Dagover] across Rooftops), 1919, set photograph from the film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

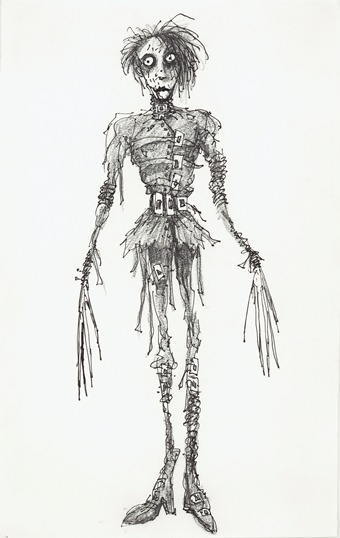

Tim Burton, Untitled (Edward Scissorhands), 1990, private collection, Edward Scissorhands © Twentieth Century Fox, © 2011 Tim Burton

Tim Burton, Untitled (Edward Scissorhands), 1990, private collection, Edward Scissorhands © Twentieth Century Fox, © 2011 Tim Burton

Some of my favorite more recent movie examples are Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, which borrows from Metropolis’s expressive set design with its modern and monumental buildings in a city where the wealthy literally live above the workers. A similar design concept distinguishes Gary Ross’ The Hunger Games. And in Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands, Edward, just like Cesare in Dr. Caligari, is an outsider with a strange condition. He’s not a villain, though look at Edward’s make-up and wardrobe. Look at his distorted Gothic castle high up on the hill within the darkest of shadows. Dr. Caligari could just as well be living there.

Alexa Schulz, Multimedia Producer