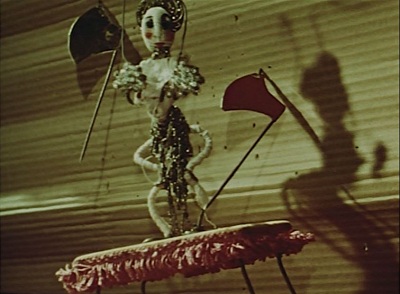

In the mid-1940s, the painter and filmmaker Hans Richter and sculptor Alexander Calder joined forces on a remarkable film, Dreams That Money Can Buy, which featured Calder’s famous Cirque Calder, a mirthful work of pure fantasy made up of delicate wire-frame miniature figures set into motion by Calder himself. This film, on view in the exhibition Hans Richter: Encounters, shows how fantasy and motion were two characteristics deeply shared by both artists. In his book, Encounters, Richter said of Calder: “The least he requires of sculptures is that they should move. And he has not been disappointed, nor have we. The earth, too, was not allowed to move until Copernicus and Galileo started it moving. . . . The twentieth century does not stand still, ‘it moves.’ ”

Hans Richter, Dreams That Money Can Buy, 1948, Musée National d'Art Moderne

Hans Richter, Dreams That Money Can Buy, 1948, Musée National d'Art Moderne

Hans Richter, Dreams That Money Can Buy, 1948, Musée National d'Art Moderne

Hans Richter, Dreams That Money Can Buy, 1948, Musée National d'Art Moderne

Calder and Richter also shared a deep interest in abstraction, as is seen in both Hans Richter: Encounters and the upcoming exhibition Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic. Richter conceived abstraction first as a painter, then as a filmmaker. One need look no further than his portraits to see how Richter progressed from portraying outward appearance to conveying an inner state of mind, as is seen in his 1918 Portrait of Arp.

Hans Richter, Portrait of Arp, 1918, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, gift of Mrs. Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, 1973

Hans Richter, Portrait of Arp, 1918, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, gift of Mrs. Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, 1973

For Richter, abstraction was a universal language linking all of humanity, much like music. In works like Orchestration of Colors, he worked in a way analogously with how composers use orchestration and counterpoint to create balanced compositions. Similarly Calder created studies of balance and form in his stabiles, a term coined by Hans Arp for Calder’s static works, some of which will be included among the fifty works on display in Calder and Abstraction. Richter’s abstraction moved swiftly from scrolls to films, some two dozen of which are in the exhibition. Richter’s earliest films, the “rhythm” films of the early 20s, Rhythmus 21 and Rhythmus 23, marked a revolution in both the history of art and film. Just imagine what it must have been like to see an abstract artwork in motion for the first time! You can experience the effect using the “experience box” wall opening in the Richter exhibition, while also seeing the same films projected across a gigantic wall, transforming them into an architectural experience.

Hans Richter, Rhythmus 21 (Film ist Rhythmus/Film is Rhythm), 1921, © Hans Richter Estate

Hans Richter, Rhythmus 21 (Film ist Rhythmus/Film is Rhythm), 1921, © Hans Richter Estate

Calder also became a master of movement. His mobiles, a term coined by Marcel Duchamp, were delicate hanging kinetic sculptures made of discrete movable parts stirred by air currents, as exemplified by Eucalyptus (1940). Both artists also shared a profound sensibility to scale, ranging from tiny and delicate to vast and powerful. Richter’s 1917 portrait of his intellectual mentor, writer and poet Ludwig Rubiner, captures its subject with a few deft strokes of an ink-laden brush. Yet he could command a much broader scale in his over 16 foot long collage-painting, Stalingrad (Victory in the East) to convey an epic turning point in the Second World War. Brought from Karlsruhe to be in the exhibition, this expansive scroll evolves from geometric to biomorphic forms to express the triumph of the people over the repressive fascist regimes then threatening Europe.

Hans Richter, Stalingrad (Victory in the East), 1943–46, ZKM|Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, © Hans Richter Estate, photo: © ONUK, courtesy ZKM|Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe

Hans Richter, Stalingrad (Victory in the East), 1943–46, ZKM|Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, © Hans Richter Estate, photo: © ONUK, courtesy ZKM|Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe

Calder’s works range from a tiny sculpture rendered from a discarded spoon (as conveyed in one of Richter’s films) to sculptures of monumental size or broad expanse. In an affectionate description, Richter portrays Calder in terms of a nickname: “He dances like a bear, he has a bear’s strength, and he often growls. With his (relatively) delicate claws he will as easily create—being a Proteus—a heavy stabile weighing twenty tons as he does a light micro-mobile weighing twenty grams. At either task he moves his immense body with the lightness and grace of Anna Pavlova.” Read Richter’s engaging commentary on Calder as well as many of the friends he had in common—including Duchamp, Léger, Man Ray, and Mondrian—in Richter’s book of reminiscences entitled Encounters, a print on demand/E-book published for the first time in English by LACMA and Prestel on occasion of the exhibition.

Don't miss Hans Richter: Encounters, which closes this Sunday, September 2.

Timothy O. Benson

Curator, Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies at LACMA