In advance of Christopher Hawthorne's talk at LACMA on Sunday, September 15, Unframed asked the L.A. Times architecture critic about the topics he'll cover in his lecture, his recent research interests, and his focus on American architecture.

Can you provide a brief overview of your talk?

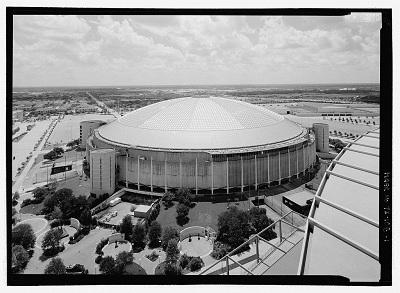

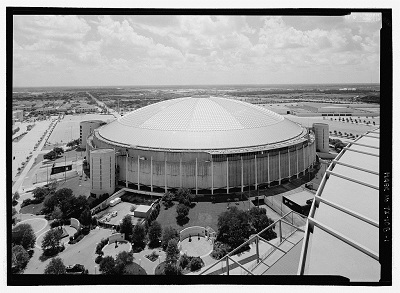

I'll be talking about the shifting relationship between American architecture and the natural world over the last 50 years, with a particular focus on how American museum design has changed over that time. The talk begins with a look at two high-profile projects that opened within a few weeks of each other in 1965: the Astrodome in Houston and the original LACMA campus by William Pereira. Both those designs, products of a highly optimistic and wealthy postwar American culture, suggested that the natural world could be controlled, sealed off, kept easily at bay. And in both cases, for different reasons, that confidence wound up being badly misplaced. At LACMA, tar and gas starting seeping into Pereira’s reflecting pools almost as soon as the museum opened.

Jet Lowe, Astrodome Looking East from Rooftof of Adjacent Reliant Stadium (New NFL/Rodeo Stadium)—Houston Astrodome, 8400 Kirby Drive, Houston, Harris County, Texas, 2004, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, HAER TX-108-1

Jet Lowe, Astrodome Looking East from Rooftof of Adjacent Reliant Stadium (New NFL/Rodeo Stadium)—Houston Astrodome, 8400 Kirby Drive, Houston, Harris County, Texas, 2004, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, HAER TX-108-1

William L. Pereira and Associates. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, c. 1965, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

William L. Pereira and Associates. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, c. 1965, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

What prompted your research into the relationship of American architecture of the last half-century to the natural world?

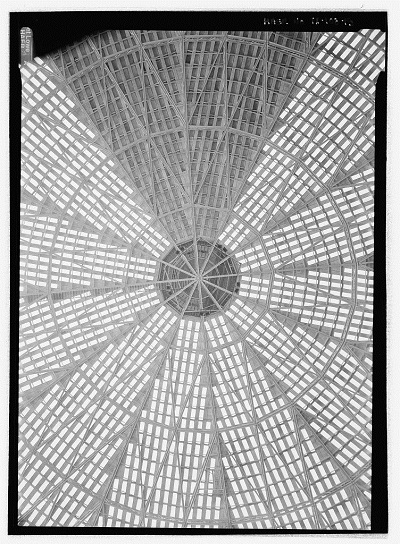

Almost a decade ago, I wrote a book (with Alanna Stang) on green residential architecture, and I've lately been interested in finding ways to expand the discussion about sustainable design beyond the quite limited checklist mentality promoted by LEED and other guidelines. The national conversation about food and food policy in this country has really grown richer, more nuanced, and more productive in recent years, thanks to Michael Pollan and other writers; I'm hoping we can broaden the discussion about architecture and the environment in a similar way. I've also become increasingly fascinated, even obsessed, by the design and history of the Astrodome.

Jet Lowe, Lamella Dome Framing Detail. Note Catwalk at 12 O'Clock and Suspended Pentagonal Light Right Gondola. Also Note Compression Ring at Crown of Dome—Houston Astrodome, 8400 Kirby Drive, Houston, Harris County, Texas, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HAER TX-108-15

Jet Lowe, Lamella Dome Framing Detail. Note Catwalk at 12 O'Clock and Suspended Pentagonal Light Right Gondola. Also Note Compression Ring at Crown of Dome—Houston Astrodome, 8400 Kirby Drive, Houston, Harris County, Texas, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HAER TX-108-15

I think you could make a pretty good case that it’s the most significant American building of the second half of the 20th century. The Astrodome’s debut was really the high point—and therefore the beginning of the end—of a very American, very confident, and ultimately very naive idea about how buildings ought to treat nature. Both the Astrodome and the original LACMA suggested that we could pretend the natural world was merely a nuisance—that we could create hermetically sealed buildings that would keep nature at arm’s length. Now, facing increasingly dire predictions of sea-level rise and other environmental threats, we’ve given up on that idea almost entirely: especially after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy, the symbolism of architecture's relationship to nature is one of anxiety, uncertainty, and even catastrophe. Architectural imagery that used to belong squarely to the world of science fiction—the cover of J. G. Ballard's 1962 novel The Drowned World, say—is now a staple of news coverage of our own cities. And the Astrodome itself is now empty and unused, in danger of being demolished to extend the parking lot of the much newer Reliant Stadium, where the Houston Texans play.

Carol M. Highsmith, Aerial of the Astrodome, Houston, Texas, c. 1980–2006, Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-HS503- 1426, LC-DIG-highsm-12687

Carol M. Highsmith, Aerial of the Astrodome, Houston, Texas, c. 1980–2006, Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-HS503- 1426, LC-DIG-highsm-12687

What are some buildings you will cite in your lecture that best respond to their landscape and natural environment?

Among museums and other buildings, what's important now is a measure of flexibility, resilience and accommodation, a sense that it's futile to pretend that we can exercise total dominion over nature. The fantastic and underrated Louisiana Museum just outside Copenhagen, by the Danish architects Vilhem Wohlert and Jorgen Bo, is one impressive example of that flexibility; another very different one is Kevin Roche's Oakland Museum, finished in 1968.

Louisiana Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark, designed by Vilhem Wohlert and Jorgen Bo, image courtesy of and © karlnorling, via Flickr

Louisiana Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark, designed by Vilhem Wohlert and Jorgen Bo, image courtesy of and © karlnorling, via Flickr

Oakland Museum of California, designed by Kevin Roche, image courtesy of and © mark.hogan, via Flickr

Oakland Museum of California, designed by Kevin Roche, image courtesy of and © mark.hogan, via Flickr

You are familiar with Peter Zumthor's proposed model for LACMA as well as his site-specific works in Europe. How do you feel his proposal would contribute to America's architectural landscape?

Zumthor's LACMA proposal is a work in progress, but at this early stage what interests me most is how it seems to celebrate the very slippery and unstable qualities of its site—the tar, especially—that the 1965 design wanted to keep under wraps and invisible. His LACMA scheme is also very different from the two fairly rational art museums he's designed in Europe; something about L.A. and this site along Wilshire has prompted from Zumthor a newly organic and fluid approach that for me is emblematic of some larger shifts in architecture.

Installation view of The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA, photo by Philipp Scholz Rittermann, © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation view of The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA, photo by Philipp Scholz Rittermann, © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA