The exhibition See the Light—Photography, Perception, Cognition: The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection presents 220 photographs from the Vernon Collection, one of the most important holdings of photography that spans the history of the medium. The presentation aims to identifying parallels between photography and vision science over time.

Since the invention of photography in the late 1830s, its materials and meanings have evolved in relation to theories about vision, perception, and cognition, which in turn reflect the social, political, and economic priorities of any given time and place. Today—as photographic images proliferate and find their way ever more directly into our consciousness—it seems not only possible but necessary to correlate developments in neuroscience with those in visual culture. This exhibition takes a historical perspective, identifying parallels between photography and vision science during four chronological periods.

We'll look a grouping of four photographs of trees featured in the exhibition in order to trace the main themes presented. In this grouping, four approaches are considered: descriptive naturalism and subjective naturalism, and experimental modernism and romantic modernism. This gathering shows how standard genres—such as portraiture, still life, and landscape—could be depicted differently, depending on the artists’ priorities and choices.

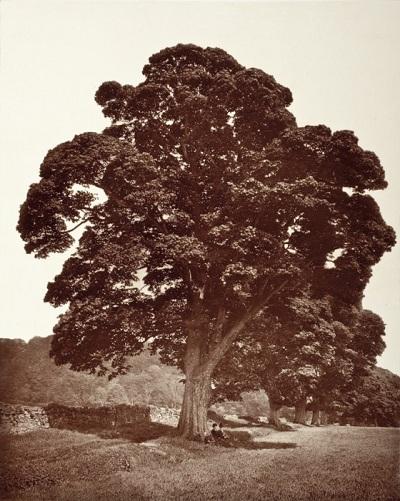

Andrew Young, Plane at Aberdour. In Old Avenue., late 1870s, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Andrew Young, Plane at Aberdour. In Old Avenue., late 1870s, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

The earliest example was made in the 1870s and represents the aims of descriptive naturalism. The photographer (Andrew Young) has tried to show maximum detail and information, framing the tree directly in the center and including small figures for scale. At the same time, in the middle decades of the 19th century, physiological optics concentrated on the eye’s information-gathering capacities, understood through new mechanical devices for measuring and recording the optical system’s response to light.

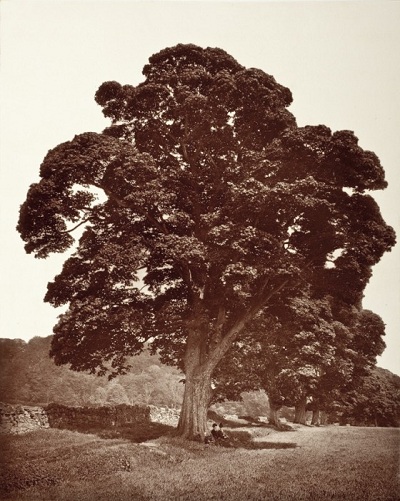

Robert Demachy, Toucques Valley, 1902, published in Camera Work, 1906, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © The Estate of Robert Demachy

Robert Demachy, Toucques Valley, 1902, published in Camera Work, 1906, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © The Estate of Robert Demachy

As the turn of the 20th century approached, both photographers and scientists became more interested in the subjective aspects of perception. Robert Demachy, a French photographer, demonstrates the tendency in subjective naturalism to manipulate the image, either in the camera or on the surface of the print, to evoke a mood rather than simply describe a scene. Similarly in the scientific realm, a new field called experimental psychology emerged, suggesting the role of emotion in perception.

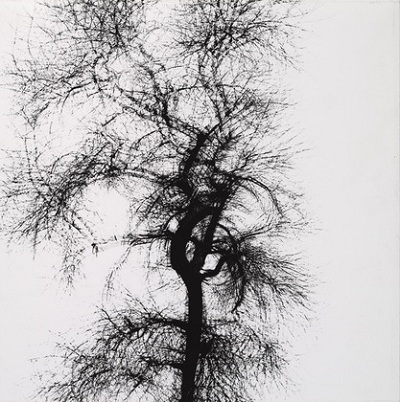

Harry Callahan, Multiple Exposure Tree, 1949, printed later, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © The Estate of Harry Callahan; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Harry Callahan, Multiple Exposure Tree, 1949, printed later, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © The Estate of Harry Callahan; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

With the 20th century came modernism and its revolutionary ideas. One form of modernism in photography, which emerged after World War I in Europe and America, was experimental modernism. This is evident in Harry Callahan’s work with multiple exposure—he is interested in seeing what happens when he moves the camera while the shutter is open. The image of a tree presents a graphic pattern of black lines on a white background, more than a representation of a specific tree in a specific landscape. It is nearly abstract, yet we do recognize it as a tree. This perceptual ability to make sense of minimal visual cues was of interest to the Gestalt psychologists who came to prominence during the period of experimental modernism.

Toward the middle of the 20th century, a more romantic form of modernism can be seen in photography, exemplified in the work of Ansel Adams, who believed strongly in the artist’s special vision while also advocating for technical mastery. In this photograph, Forest, Early Morning, Mt. Rainer National Park, Washington, Adams establishes a subtle range of tone, so as to convey a mood of hushed reverence for nature while also capturing each distinct leaf and texture. The issue of light-and-dark contrasts was of primary concern to both photographers and vision scientists at this time—not only must these contrasts be managed in a photographic print in order for the image to make sense, contrasts in the physical world allow us to locate objects and navigate in our environment.

Britt Salvesen, department head and curator, the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography