Building on the excitement of LACMA’s announcement last month of its new Art + Technology Lab, I thought it would be interesting to look back at one of the projects from LACMA’s original Art and Technology Program (A & T), which ran from 1967 to 1971.

Cover of A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1967–71

Cover of A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1967–71

For the first A & T, curator Maurice Tuchman invited 64 artists to be matched with companies working in “coastal” industries such as aerospace, scientific research, manufacturing, and cinema/television. One of the 23 artists to be paired successfully with a corporation was Tony Smith—a figure familiar to many LACMA visitors for his monumental sculpture Smoke that graces the atrium of the Ahmanson Building (and was the subject of Liz Glynn’s performance The Myth of Pure Form last month).

Tony Smith, Smoke, 1967, fabricated 2005, made possible by the Belldegrun Family’s gift to LACMA in honor of Rebecka Belldegrun’s birthday

Tony Smith, Smoke, 1967, fabricated 2005, made possible by the Belldegrun Family’s gift to LACMA in honor of Rebecka Belldegrun’s birthday

Smith initially expressed his interest in doing an inflatable soft sculpture he described as “a type of structure in which all of the compressive elements would be made of air or gas in compression.” When that proved to be unfeasible, then-associate curator Jane Livingston suggested Smith work with the Container Corporation of America, a manufacturer of paperboard products including folding cartons, paper bags, and fiber cans.

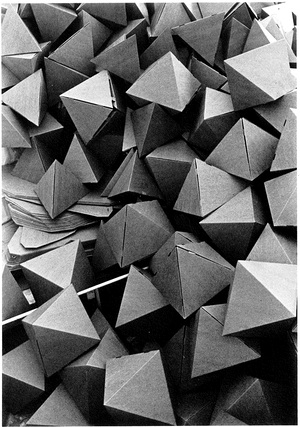

The Container Corporation turned out to be a good fit for the artist. Smith was already in the habit of making models for his large-scale sculptures by gluing together hundreds of maquette modules. These individual paperboard components were typically tetrahedrons (four-sided forms with triangular faces) or octahedrons (eight-sided forms with triangular faces).

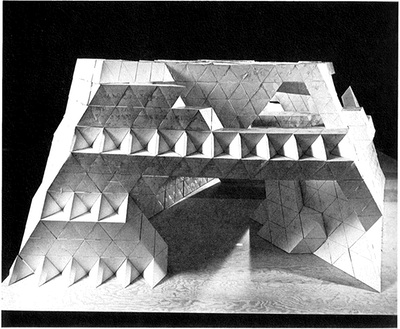

![Tony Smith next to a model composed of tetrahedrons and octahedrons (with additional maquette modules in the foreground) [Photographer: Malcolm Lubliner]](/sites/default/files/attachments/jk-at71.jpg) Tony Smith next to a model composed of tetrahedrons and octahedrons (with additional maquette modules in the foreground), photo by Malcolm Lubliner

Tony Smith next to a model composed of tetrahedrons and octahedrons (with additional maquette modules in the foreground), photo by Malcolm Lubliner

In most of Smith’s sculptures prior to his A & T project, the component-nature of a sculpture’s composition became invisible once the work was fabricated in steel at a large scale; the individual modules disappeared into the gestalt of the sculpture’s overall form (as, for example, in Smoke). But working with the Container Corporation, which could die-cut corrugated cardboard, Smith realized that he could replicate his method of working on models at a monumental scale. In August 1969, the company made Smith two sample corrugated units (one tetrahedron and one octahedron), each two feet on a side. After he approved of the samples, the company cut hundreds of small paperboard modules that Smith used to design a model for a cave-like sculpture—its shape inspired by bat caves he had seen in Aruba—to be executed for the A & T exhibition at the U.S. Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan.

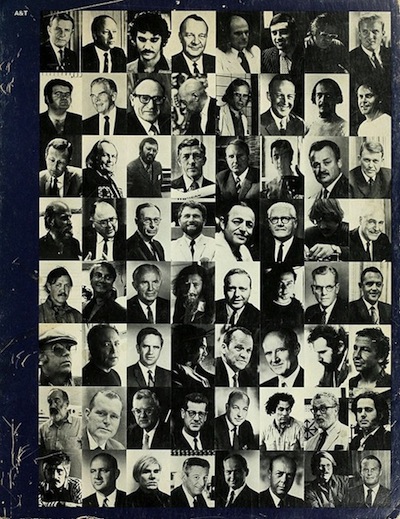

Smith’s model, constructed of four-inch paper modules, for his work at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, photo by Hans Namuth

Smith’s model, constructed of four-inch paper modules, for his work at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, photo by Hans Namuth

For Expo ’70, palletized flats of precut cardboard manufactured by the Container Corporation were shipped to Japan, where William Lloyd, a manager of design for the Container Corporation, was tasked with overseeing the construction of the full-size sculpture. Over a period of five weeks, some 2,500 modular components were folded, taped, and joined together. The completed sculpture was a massive cave-like structure that viewers were able to enter and exit.

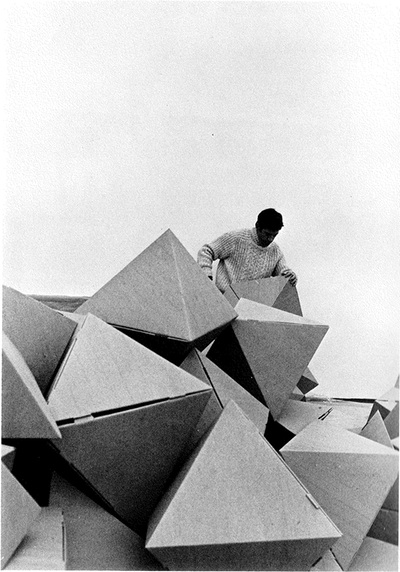

Construction in progress for Tony Smith’s sculpture at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, photo by Tami Komai

Construction in progress for Tony Smith’s sculpture at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, photo by Tami Komai

Construction in progress for Tony Smith’s sculpture at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, photo by Tami Komai

Construction in progress for Tony Smith’s sculpture at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, photo by Tami Komai

Interior view of Smith’s sculpture at Expo ’70, photo © Museum Associates/Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Interior view of Smith’s sculpture at Expo ’70, photo © Museum Associates/Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Smith was one of the fortunate artists in the original A & T to be matched with a sympathetic and compatible corporation—some of the participating artists did not find suitable corporate partners, and still others who did match with companies were unable to realize the works they proposed for various technical or logistical reasons. The new Art + Technology initiative, while taking inspiration from the spirit of innovation of the original A & T program, is different in structure. Rather than be matched with individual companies, participants will have the opportunity to work in residence at LACMA’s new Art + Technology Lab housed in the Balch Research Library: more details can be found in the Request for Proposals (opens PDF). Artists have until January 27, 2014, to submit applications.

Jennifer King, Wallis Annenberg Curatorial Fellow, Modern Art