Fútbol: The Beautiful Game, on view at LACMA through July 20, fascinates me for a number of reasons. First of all, I am Italian, and football is serious business to me, especially when comes to the World Cup. (It’s a cliché, I know, but it’s true!) Secondly, football was the subject of an exhibition organized in 2004–5 by Harald Szeemann, one of the most prominent curators of the 20th century. Poetically titled Rundlederwelten (Round Leather Worlds), the project was one of the last recorded in Szeemann’s monumental archive, which is currently being processed by the Getty Research Institute. It’s exciting to see in Los Angeles an iteration of Szeemann’s idea, and I wanted to take this fortuitous opportunity to look at Fútbol through the lens of Szemann's original proposal.

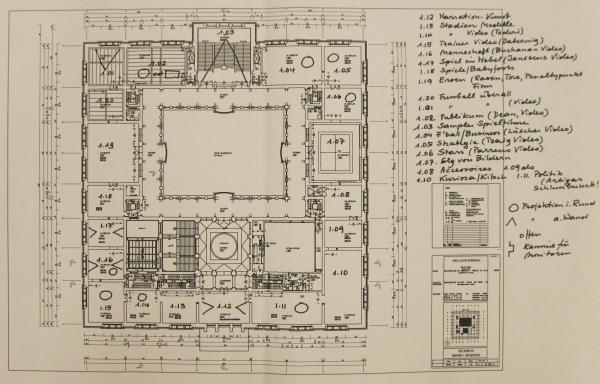

(Click image for full size): Harald Szeemann, floor plan of the Martin-Gropius-Bau with notes on possible themes and artists for his exhibition Rundlederwelten, undated (approximately 2004), Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

(Click image for full size): Harald Szeemann, floor plan of the Martin-Gropius-Bau with notes on possible themes and artists for his exhibition Rundlederwelten, undated (approximately 2004), Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

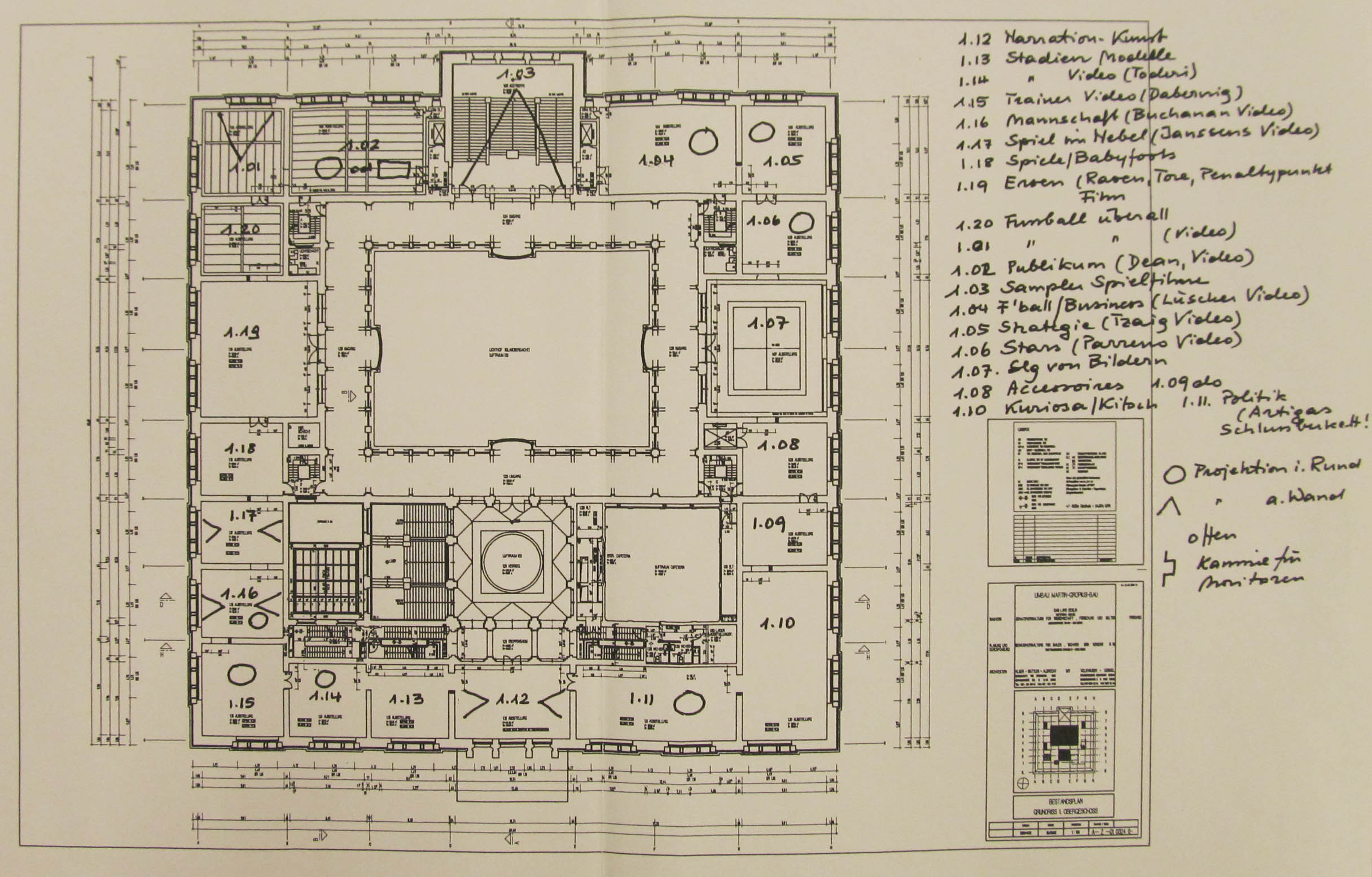

(Click image for full size): Harald Szeemann, hand-drawn floor plan of the Martin-Gropius-Bau, undated (approximately 2004), Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

(Click image for full size): Harald Szeemann, hand-drawn floor plan of the Martin-Gropius-Bau, undated (approximately 2004), Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

Rundlederwelten was supposed to open in the upper floor of the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin and, like the LACMA exhibition, the show was meant to coincide with the World Cup, which was held in 2006 in Germany. (It was won by Italy—just saying.) Following Szeemann’s sudden death in February 2005, his family asked another curator to continue the project, given that many of the artworks that were to be part of the exhibition were already in the process of being made. Loosely inspired by Szeemann's ideas, curator Dorothea Strauss opened the exhibition in the same venue in October 2005.

Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon, Zidane: A 21st-Century Portrait (detail), 2006, © Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon

Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon, Zidane: A 21st-Century Portrait (detail), 2006, © Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon

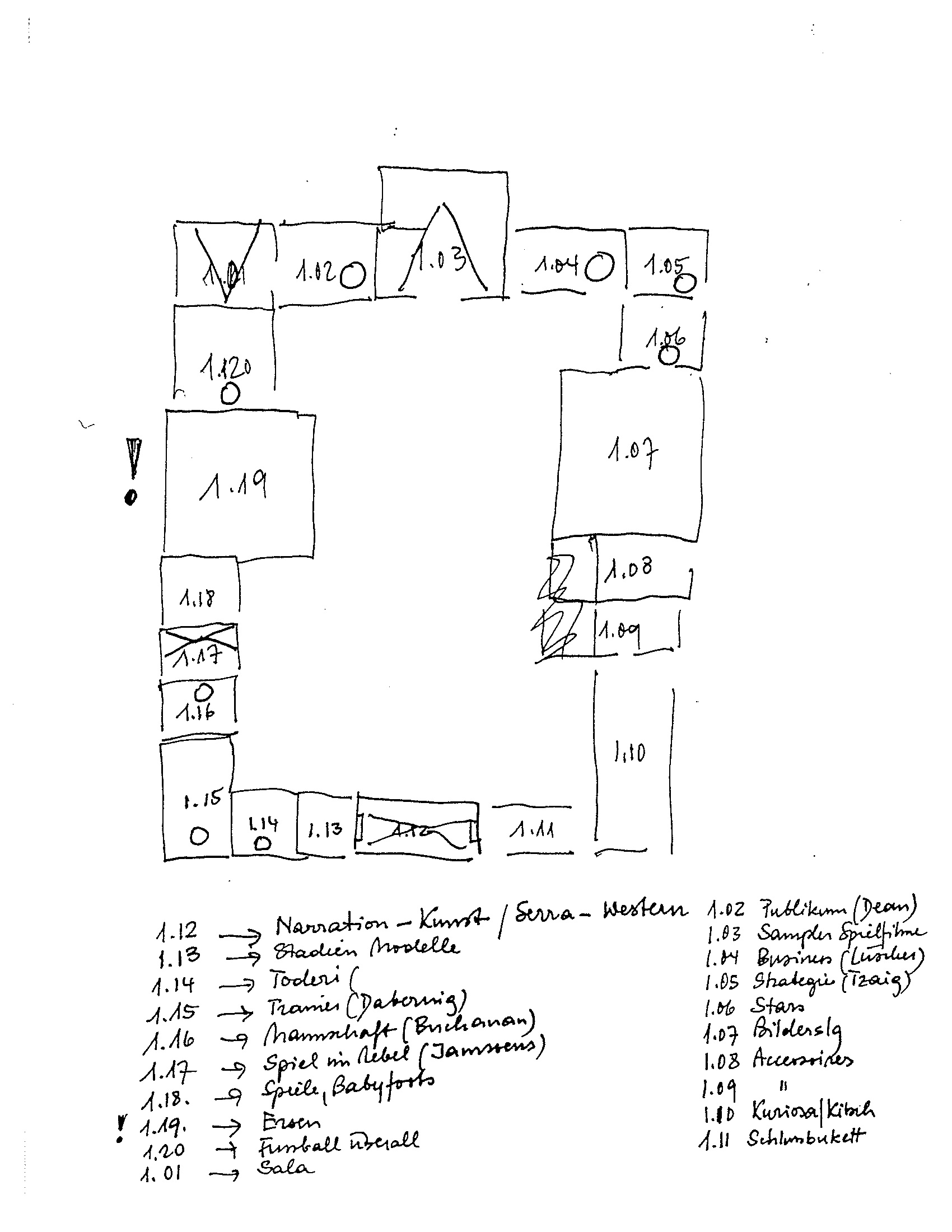

Walking around in the LACMA show, it was interesting to spot a number of artworks that Szeemann was also thinking to include in Rundlederwelten, such as the monumental Zidane: A 21st-Century Portrait (2006) by Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon. Parreno and Gordon made this work around the time that Szeemann was organizing his exhibition, and Szeemann was going to premiere it at the Martin-Gropius-Bau. Some artworks by Andreas Gursky and Antoni Mutadas were also on the curator's checklist, along with Caryatid (2004) by Paul Pfeiffer and Volta (2002–4) by Stephen Dean, both that are also on view in LACMA’s exhibition.

Stephen Dean, Volta, 2002–3, Collection of William and Ruth True, Seattle, Courtesy of the artist and Baldwin gallery, Aspen, © Stephen Dean

Stephen Dean, Volta, 2002–3, Collection of William and Ruth True, Seattle, Courtesy of the artist and Baldwin gallery, Aspen, © Stephen Dean

(Click image for full size): Harald Szeemann, notes on Paul Pfeiffer's work, likely taken during a studio visit, undated (approximately 2000–2004), Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

(Click image for full size): Harald Szeemann, notes on Paul Pfeiffer's work, likely taken during a studio visit, undated (approximately 2000–2004), Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

Having the privilege to research a private archive also means having access to the “backstage” of a project and all its different phases and issues. We see, for example, a number of prominent artists who refused Szeemann's invitation. Hans Haacke, whom the curator approached, seemed skeptical about the possibility of making a cultural contribution about a sport event; he was also irritated by the global hysteria about football.

Research material on sports, collected by Harald Szeemann for his project Rundlederwelten, Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

Research material on sports, collected by Harald Szeemann for his project Rundlederwelten, Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

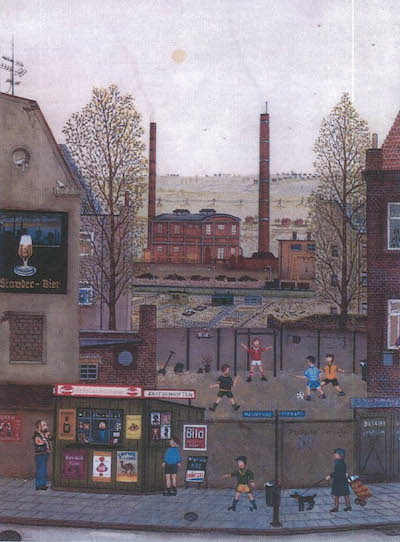

The response by contemporary visual art represented just part of a larger inquiry. The fascination with the game was apparent throughout mass culture. Szeemann was interested in the ephemera around football. He collected naïve paintings on football, recordings of songs sung during the games, stickers depicting football players, postcards, and models of stadiums, which were gathered in collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron. Furthermore, Szeemann was corresponding with the leader of a German association, who was fighting against racism at the games, and the curator was considering screening a documentary about Palestinians and Israeli citizens playing together.

Images of naïve paintings by unknown artists, collected by by Harald Szeemann for his project Rundlederwelten, Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

Images of naïve paintings by unknown artists, collected by by Harald Szeemann for his project Rundlederwelten, Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

In Szeemann's vision, sports were just a vehicle that allowed artists to comment on broader topics, such as “business, mass psychology, voyeurism, media, cult of the relics, . . . philosophy of the everyday life, politics, architecture, religion,” as he stated in an unpublished note. As in many of his projects, Rundlederwelten would then have been an acute survey about the role of visual production in our society through the analysis of one of our recent obsessions.

Pietro Rigolo, Special Collections Archivist, Getty Research Institute