It’s strange that dolls inspire such horror in so many people. They are, after all, designed for the enjoyment and pleasure of young children—the vulnerable and innocent among us who, presumably, we do not desire to terrify in a systematic way. But the fact remains that, despite the best intentions, dolls are, for many people, the stuff that nightmares are made of.

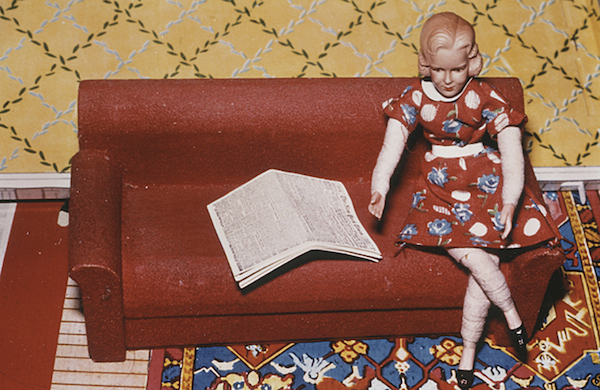

I’ve come up against this more times than I can count since I decided to organize the installation Playthings: The Uncanny Art of Morton Bartlett, on view at LACMA through January 31, 2015. The show consists of 12 large color prints of lifelike dolls produced by Bartlett in the mid-1950s, as well as material pulled from his personal archive. Over a period of roughly 25 years beginning sometime in the mid-1930s, he meticulously constructed and painted 15 child dolls—complete with clothing that he sewed by hand—which he then photographed in his home studio. They are fantastic creations, but despite that, the most frequent comments I get in casual conversation go something like this: “How creepy they are!” “What on earth are they?!” Not that I blame anyone for feeling that way.

Bartlett was not an “artist” in the conventional sense. He worked a variety of odd jobs before settling on freelance photography as a profession. Creating and photographing his dolls was only a “hobby,” as he called it in a rare statement about his creations. He was what has come to be called, somewhat controversially, an “outsider artist”—someone who produces work outside an established and recognized market and audience for art. Despite the prodigious numbers of photographs that he produced, he kept his dolls hidden from even his most intimate friends, and it seems he never spoke of them again after he locked them up in a cabinet in his Boston brownstone in 1963. It was only once his work was discovered by the antiques dealer Marion Harris soon after Bartlett died in 1992 and, more recently, through the enterprising collecting of Barry Sloane, who produced the beautiful color prints from Kodachrome slides now in LACMA’s collection, that Bartlett’s work started circulating within the mainstream art market.

The patchy details of his life—born in Chicago, orphaned at eight years old, adopted by a wealthy Massachusetts family, student at Phillips Exeter Academy and then Harvard University—are often recited as a way of providing some kind of biographical detail to hold on to. In truth, however, very little is known about the man, nor of his motives for creating these dolls. Despite the incompleteness of his biography, it has been the primary way in which the work has been understood, most notably, Harris’s claim that the dolls were an attempt to reconstitute the family that he lost as a child.

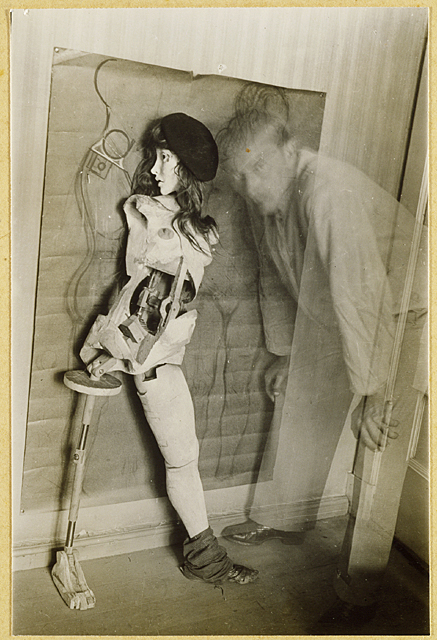

Bartlett was by no means alone in finding creative inspiration in his chosen subject. Images of dolls constitute a sort of micro-genre in the history of photography, from the earliest years of the medium. Dolls and mannequins were of particular interest to Dada and Surrealist artists of the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s. Perhaps most famously, Hans Bellmer created dolls with moveable appendages, which he photographed propped against walls, sprawled out on his bed, and fully separated into their constituent parts. For Bellmer and the Surrealists who championed him, his figures were the ideal Surrealist objects—symbols of naivety, femininity, sexual fantasy, and political victimization. The historical concurrence of the creation of Bellmer’s dolls—the first one was created in 1933—and Bartlett’s is tantalizing.

Bellmer’s work inspired a number of artists of the 1970s and 1980s who used dolls to comment on identity and the social politics of the body. Cindy Sherman’s photographs of mutilated dolls are perhaps the most clearly referential of the earlier artists work. Less violent in appearance, but clearly interested in the kinds of surreal and disturbing effects of dolls, can be found in the work of Laurie Simmons, who has used dolls in a variety of projects since the 1970s. Bernard Faucon’s Summer Camp, among other series, used dolls and mannequins tinged with Bellmer’s subversive sexual undertones. He presented them in ways that share much with Bartlett’s color-saturated, theatrical world of artificial children engaged in unsettling forms of play.

One commercial artist and author who overlapped chronologically with Bartlett was Dare Wright, whose book series Lonely Girl featured photographs by her of the eponymous doll, starting in the late 1950s. Bartlett’s images share perhaps most with Wright’s, in terms of sentiment and fascination with the naïve emotional lives of children. She also shares a Geppetto-like quality with Bartlett, expressing that basic human fascination with breathing life into dolls—one of her books is titled Make Me Real.

It is exactly this possibility—fantastical as it may be—of an inanimate surrogate transforming into animate flesh that often inspires the fear of dolls. Dolls are designed as versions of humans, and it tends to be true that the more human they become, the more terrifying they tend to be. Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay "The Uncanny," a foundational text on the psychology of the uncanny, roots it in the confusion between human and automaton, citing E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann (1816), which focuses on a lifelike doll. Uncanniness is the disturbing sensation of encountering something simultaneously familiar and foreign, resulting in the paradoxical response of fascination and repulsion. The feeling has more recently entered popular parlance in studies of the “uncanny valley” produced by robots and computer-generated graphics that are nearly-but-not-quite-human.

Popular culture—particularly horror and science-fiction film—has certainly played its part in contributing to the anxiety around dolls. The current LACMA exhibition Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s features elements of one of the earliest such films—Metropolis—complete with a replica of the robot who comes to life in the film. In more recent decades, schlocky horror has played on the public’s fear of nefarious dolls coming to life—in movies with colorful titles, such as Child’s Play, Dolls, Demonic Toys, and Dolly Dearest, as well as the more recent blockbuster, Annabelle. So when a news story recently broke about mysterious dolls appearing on porches in San Clemente, reputedly resembling the young girls who resided within, we might be excused for thinking the worst.

The fact that Bartlett made such a focused attempt to create lifelike child mannequins—the dolls are all fully anatomically correct—only adds to the unnerving qualities of the photographs. If he was a latter-day Pygmalion, attempting to animate his sculptures—to what end was he working this magic? Like Henry Darger, the graphic artist who had a similar decades-long obsession with representations of young children, Bartlett has fallen victim to posthumous chargers of questionable sexual intentions.

Bartlett’s motives for creating and photographing his dolls might never be known in all of their complexity, but it is clear that he had a keen interest in the interior lives and psychology of children. His photographs seek to accomplish that long-sought dream of animating the inanimate. He breathes life into the dolls with his camera, imbuing each with vitality and their own personality. It is this conjuring that lends them their uncanny—or, to put it more bluntly, creepy—quality. Had he not been so interested in creating convincing approximations of real children, rendered with such care and fidelity, they might not inspire such unease. But what would be the fun in that?