My name is Nicolas Orozco-Valdivia, and I just finished my second year at Pomona College in Claremont California, where I am an art history/studio arts double major. I want to be a curator once I’m done with the studies required to do such work. I grew up in Alhambra, California; my parents are from Boyle Heights, Los Angeles; and their parents are from Jalisco, Zacatecas, and Tijuana, Mexico. I am thrilled to have been selected as a fellow in the first class of the Andrew W. Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship Program at LACMA. I thank all involved, but especially my family, who are the most caring.

I was asked to write about 300 words for Unframed as a means of introducing myself to all of you. 300 words got me thinking about 300, Frank Miller’s 1988 comic book (or graphic novel if you like) with colors by Lynn Varley. It is, frankly, an illegible comic. Yet among the misleading composition, incomprehensible jump cuts, and obfuscating streams of Persian blood, there is something profound at work. Or rather all this illegibility is profound. 300 reminds me of the vast amount of work that goes into interpreting the endless fury, jumble, and muck of our lived experience. It reminds me that as an artist, writer, teacher, or curator, the stories we tell are always constructed. I’ve been given access as a fellow to the specific way in which museums make stories out of this all-messy world, using physical objects as a means of interpreting the past, questioning the present, and envisioning a future.

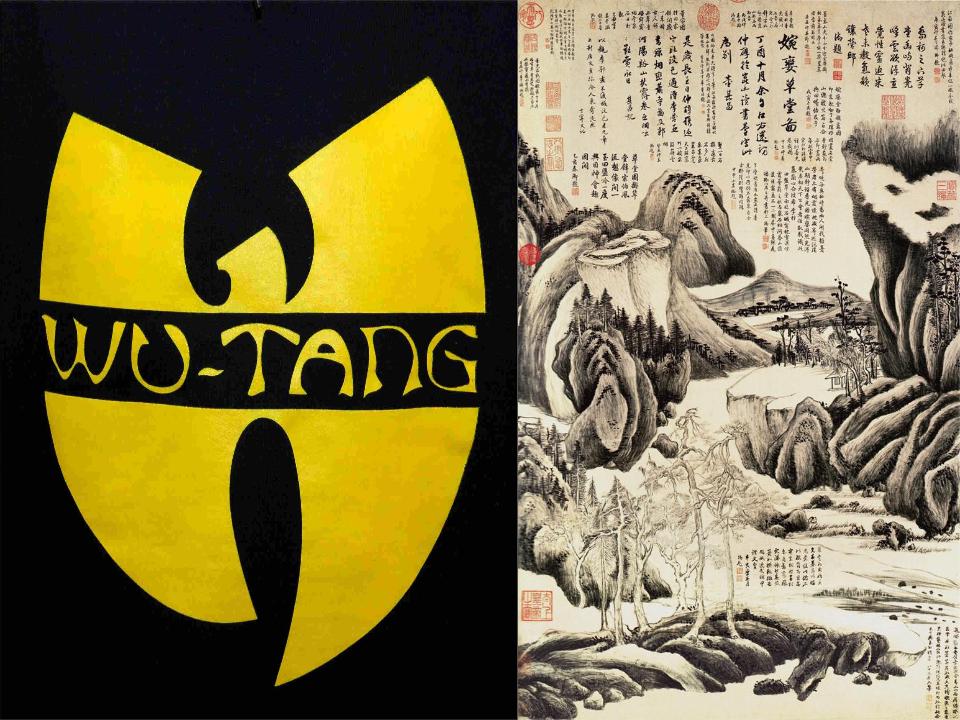

Stephen Little, Florence and Harry Sloan Curator of Chinese Art, and Department Head, Chinese and Korean Art Departments, and Hilary Walter, National Fellowship Coordinator, are my access points to the pulsing innards of the museum body at LACMA. Stephen has offered me insights from his curatorial mind about the material and political intricacies involved in collecting, organizing, and presenting cultural objects. Behind closed doors, Stephen pulls out centuries-old bronzes, ceramics, and silken scrolls, the material objects I had studied as projections onto walls of my Chinese art history course. Resting my fingers on real metal and cloth helped me focus my visual and historical analysis and provided new insights into a time and place that seemed very distant from my own. The insights and connections I made during intimate moments of object handling influenced the form of my final art history paper, "The Wu-Tang Clan and Dong Qichang: A Comparison," which took on the highly influential 17th-century painter Dong Qichang.

With Hilary I travel beyond the Chinese and Korean Art Department. To date, our activities have included touring an exhibit with Terri and Michael Smooke Curator and Department Head of Contemporary Art Franklin Sirmans; learning how to properly handle paper and objects in the conservation department with Erin Jue, Soko Furuhata, and Natasha Cochran; meeting with LACMA’s CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan; and pondering visitor experience with senior content specialist Kirstin Bengston from the Education Department. Outside the museum proper, we visited the Getty Research Institute to see box after box of Harald Szeemann’s archives; we ventured through Beverly Hills gates to wonder at the moneyed walls of the Frederick R. Weismann Art Foundation’s home/museum; and we exited a freeway to see the unmarked warehouse where oversized artwork from LACMA’s permanent collection is stored. Among these disparate points both far afield and close to home, scholarly insights are exchanged, artwork is transported, and emails reverberate, all in the service of communication, all in service of presenting a story.

I have learned that the creation of a museum exhibition's story does not spring forth complete from the mind of one single author, but rather develops in conflict and reaction to various intellectual perspectives and material limitations. At LACMA, I am beginning to understand the process that brings cultures from many places in the world, in all their 300-style senselessness, to the polished intelligibility of a museum exhibit. For all these reasons my experience as a Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow has been entirely enlightening and enjoyable, that is, entirely unlike reading Frank Miller’s 300.