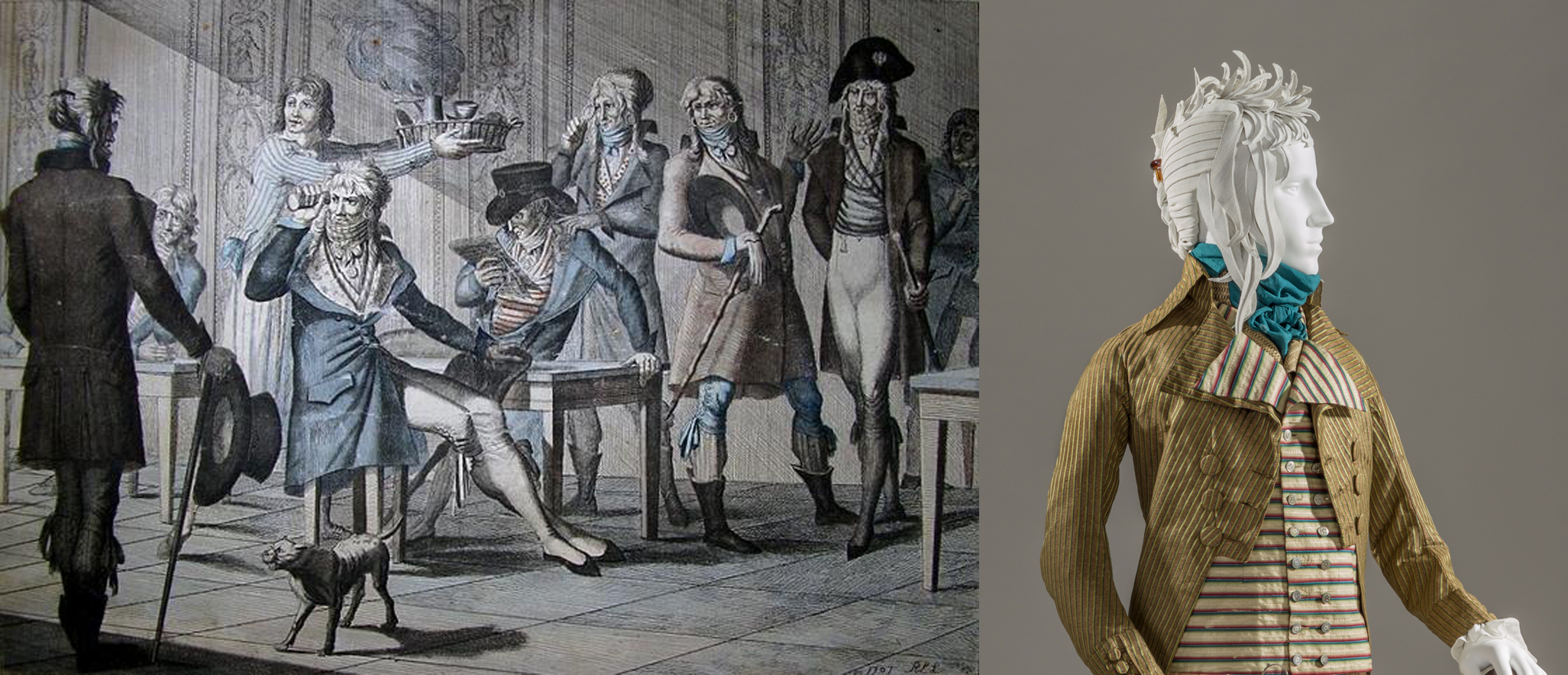

One of the most frequently asked questions from visitors to Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015 is about the wigs that complete the numerous mannequins on view. When co-curators Sharon Takeda, Kaye Spilker, and I first began to organize this 300-year survey of menswear, we realized that men’s hairstyles varied just as much as the cut of their suits. To fully reflect the evolution of men’s fashion and their accompanying silhouettes, we determined early on that fully dressed ensembles needed wigs to achieve our vision of display.

Enter Deborah Ambrosino, who took on the herculean task of creating all of the wigs displayed in the exhibition and photographed in the catalogue. I sat down with her recently to learn more about her background in film and her process in making exhibition wigs.

What is your current profession?

I am a specialty costume keyperson for film. I work in the costume department doing research and development, prototyping and making everything and anything except sewing clothes.

What movies have you worked on?

The last few years, it has mostly been Marvel projects, and before that it was more costume-focused, like Snow White and the Huntsman, Cowboys and Aliens, Memoirs of a Geisha, and Big Fish.

Having heard about your specialty costume experience, Sharon, Kaye, and I invited you to LACMA early in the planning process to discuss potential ideas for wigs in Reigning Men. Can you talk about how you came up with your concept for the materials you would use?

I remember asking what technically needed to be improved upon from wigs used in exhibitions past, and what you wanted out of this project. I believe it was Sharon who said we want the next thing, we want new. Paper has been used for the last 20 years and this exhibition was going to present menswear in a new way.

I thought about what you needed and how I could make it special. And I wanted whatever material I used to tie specifically to the theme of men and menswear.

I thought, what is masculine? While a lot of what is considered masculine seems to have morphed over the last 300 years, the art and rules of tailoring have remained essentially the same. So I looked at the fabrics used in tailoring. I realized that the hair canvas used to shape the torsos of men’s suit jackets had the widest variety of malleability, texture, and color.

This idea, along with the variety of swatches that I brought to our first meeting, seemed to interest everyone.

It definitely did. And what interested you in taking on this project of making wigs for Reigning Men?

After that first meeting, it was an opportunity for me to do something new, and to take it to the end. The process was new; I’d never worked for a museum before. It seemed exciting—I just hoped it would be OK.

Well, it definitely was OK. Take us through your process of how these wigs were made.

You sent me a huge binder of research along with the various mannequin heads and it was time to back up all the happy talk. The styles and the mannequins themselves were just an overwhelming blur, but with time and your help I was able to slowly understand the scope of what we were trying to achieve.

Yes, we had a lot of different hair styles and five differently shaped mannequin heads. Where did you even begin?

I started with making prototypes of a few hair styles that you considered a good representation of the show. Five core styles for different eras. Once I cracked those looks, we were confident in going forward. I think for you at LACMA it was the proof that it could be done. And it was, with lots of trial and error, and collaboration and input.

How do you think your film experience informed your approach in making these?

A lot of my techniques came from millinery—knowing how to shape cloth into a three-dimensional look. I did this through stretching, molding, and steaming the hair canvas. As the project evolved, my training as a specialty costume maker allowed me to develop the more unusual or special styles.

Not knowing about [the history of] hair [styles] helped because I was able to look at your research, then bring the style down to its essence. It’s about taking away, editing, and making the wig say the most with the least. You don’t want to draw too much attention; the wigs needed to enhance, not overwhelm.

How long did it take to make some of these styles?

Not including the “specials” [Afro, macaroni, Mohawk, early 18th century, and incroyable wigs], on the average, 14 hours. That was just the making stage and doesn’t include the R&D and the prototypes. As well as 225 yards of fabric used over the course of two years!

What took the longest?

It’s got to be the early-18th-century full-bottom wig—74 hours. That’s because I had to make it twice; sadly the techniques I used on the first go did not work. I knew that all of those curls had to live and survive even with the best of care. The Afro was the runner-up.

Which style was the hardest to conceive and create?

I know it’s simple, but the 18th century. It is so simple and I went back again and again to make it better. Oh those curls! I made them four times and you’ll see all four different styles in the show.

Really? I thought you were trying to make them different!

I was trying to make them different to make them better! And the “Darcy” [an early 19th-century hairstyle named after Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice]. There are so many little pieces in it. . . . It just took what it took.

Do you have a favorite?

I’m sure I do. Gosh. That shag, I love that shag. I think that it was the first prototype—the shag and the fade—and they work so well. The shape is so simple, [so] elegant but it says it all. Just look at the Etro.

How are you feeling now that it’s done?

I’m happy, satisfied, and relieved that it all worked out. Happy that our collaboration worked. Sometimes I look at it and I think, that looks really good! It really captures what we were trying to create. There are two styles I’d like to do over again, but that’s pretty good odds considering 116 were made, not including facial hair. It is amazing.

See Deborah Ambrosino’s wigs in Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015, on view until August 21, 2016.