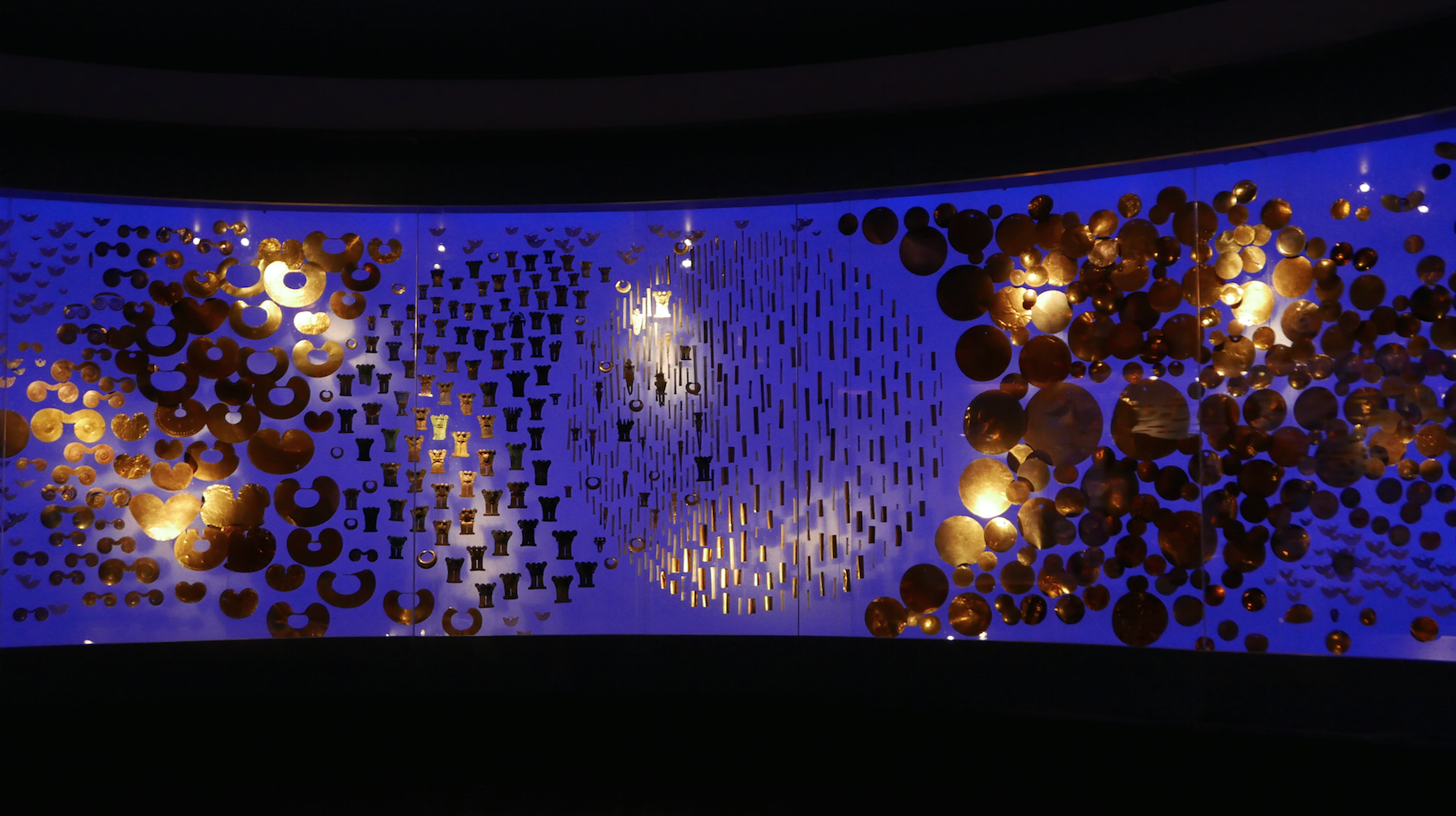

In 2014 I joined the art of the ancient Americas department as a postdoctoral curatorial fellow, charged with researching and creating exhibitions using the permanent collection of ancient Colombian ceramics. This large collection of 914 objects had been acquired from a private collector in 2007. It quickly became clear that LACMA has one of the best—if not the best—collection of ancient Colombian ceramics of any public institution in the United States, spanning the entire geographical and chronological range of ancient Colombia. However there were also a number of challenges in working with these objects. First and foremost, the arts of ancient Colombia have not yet enjoyed the scholarly attention they deserve. While goldwork from the region has long been appreciated and exhibited throughout the world, art in other mediums, such as clay, has largely been consigned to obscurity.

From a curatorial point of view, this means there are few publications to tell us about the history and particularities of these objects. That is not to say that no research has been done, but, to give you a sense of the situation, I did a quick keyword search in the WorldCat.org library database for “ancient Colombia,” which yielded 2,790 hits. Replace the word “Colombia” with “Mexico” and you get 25,000 hits. In sum, detailed information based on solid research that is directly relevant for the objects in our collection is hard to come by.

I was lucky to be able to personally examine almost the entire collection, identifying what I thought were the best pieces for exhibition, as well as some pieces about which I had my doubts. In any field where there are objects of value, there are people making and selling reproductions and forgeries. In the case of ancient Colombian ceramics, this risk is reduced, because the objects are not so well-known and not so desirable for collectors, and therefore not so valuable. On the other hand, the fact that they are not well-known increases the risk of collections ending up with modern forgeries, because the knowledge to identify how a “real” ancient Colombian ceramic should look and feel is largely lacking.

In November 2015 we were able to invite experts from Colombia to LACMA to help us work with our collection; this included Maria-Alicia Uribe (Director of the Gold Museum in Bogotá), Colin McEwan (director of Precolumbian studies at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections), and Santiago Giraldo (Director of Colombia for Global Heritage Fund). As we walked through our small installation of Colombian ceramics, they shared their thoughts, expressing wonder, excitement, but in some cases also doubt. Working with Colombian objects on a daily basis, Maria-Alicia Uribe and Santiago Giraldo were much more familiar with the idiosyncrasies of the different styles represented in our pieces, and they quickly spotted old breaks and repairs: a reconstructed leg on a figurine, for example, was noticeable to them even through the glass of the vitrine.

After their visit, I was determined to re-examine as much as possible of the collection. As well as learning about the forms and iconography, we needed to learn more about the manufacture of these objects, in order to understand them better and to distinguish ancient from modern creations. I carefully examined surfaces and interiors, paints, incisions, burnishing marks, paste-colors, temper, and of course, form, design, and iconography. I tried to get a better feel for the objects, their weight, surface finish, and form, so that I would notice anything unusual. Wherever possible I enlisted the help of our conservators and conservation scientists, using the microscope, for example, to more closely examine stains, deposits, encrustations, and wear as a potential sign of age. We compared it to knowledge recently gained from an intensive study of our Maya vase collection. While insightful, here too we realized that we didn’t have the necessary level of experience of specifically ancient Colombian materials to know what to look for or what to expect.

And so, armed with a wealth of photographs and questions, we headed to Colombia in search of answers.

Maria-Alicia Uribe had prepared for us a week-long workshop of object-viewings, tailored specifically to the objects in LACMA’s collection. Her staff had selected comparative objects from their vast collection, and, with the objects before us, we spent the week in conversation with both in-house and invited experts. Santiago Giraldo joined us once more to discuss the objects from the Tairona culture where his expertise lies. We were allowed to handle the objects (with gloves, of course!), to photograph and even to film, which many museums do not permit visiting scholars to do. We spoke freely on which objects they thought were modern forgeries, and how they came to this conclusion. We learned that, more often than not, it is not complete reproductions but pastiches that are the problem; objects that are made up of authentic fragments but that have been completed using modern pieces, or ancient fragments that have been combined to create a new object. We spoke with archaeologists, anthropologists, conservators, and metalwork experts, looking at complete objects, fragments, and X-rays. Some of their objects were almost identical to ours; in other cases, objects from our collection appeared unique and had everyone looking more closely.

Perhaps the most eye-opening experience was during our visit to the Museo Arqueológico in the Casa Marqués de San Jorge. There we met Victoriano, though he also referred to himself as Pix wala, which means “man of knowledge” in the Nasa Yuwe language of his people, the Paez. Victoriano worked with the Museo Arqueológico to play their ancient musical instruments—instruments of the kind we also have in our collection. Hearing the music that could be teased from these clay flutes and ocarinas—some over a thousand years old—was overwhelming. These were not mere “whistles,” as they are so often classified in museum databases—this was music, the kind that accompanies life and death, dawn and dusk. Victoriano put it like this:

"These melodies did not come from outside, but have existed here since times immemorial, here, in our minds, in our hearts, and they still remain in the bowels of nature. […] The people who don't know of this, they will think these are just objects, something that ‘the Indians’ of some period made. But no: these have a purpose; these are living beings. There are spirits here. And they are very happy here. And though they don't shine as much as the gold, they shine thanks to their knowledge and their worth in the moment in which they are given their function.”

I am glad to have walked away from this experience with a newfound understanding and respect for these ancient objects in our care, and a reminder of what a privilege it is to be able to handle (and learn from) them. Informative as this first trip was, our work is far from done. Many questions remain, questions that are shared by the staff at the Museo del Oro and Museo Arqueológico in Colombia, which shows once more how important such collaborations are. Outcomes from investigations that LACMA will carry out following this trip will be shared with the Museo del Oro and vice versa. We will undoubtedly make another trip, armed with new data and new questions, and we hope to bring experts from Colombia to LACMA to work with our collection and our conservation staff directly.

.jpg)

Overall, it was rewarding to realize that LACMA’s collection is truly very good, both in terms of authenticity but also in terms of the range and quality of the ceramics. Some of these objects in our collection may be among the best produced by their respective cultures. They have lost their context; some have lost their gold or feather adornments, and many have lost the meaning and power they once had for the people who made and used them. But, as Victoriano demonstrated, they are not silent. Our work is designed to bring these long-forgotten objects, peoples, and ways of seeing the world back into focus, affording them their place in the history of world cultures.