Who doesn’t love chocolate? To celebrate “National Chocolate Day,” which is tomorrow, October 28, I want to recognize the importance of chocolate—also known as cacao—in the ancient Maya civilization. The ancient Maya consumed chocolate as a drink, which was sometimes mixed with substances such as corn and flavored with spices and flowers, and as a sauce on corn tamales and other foods. Chocolate was so valuable to them that they produced many fine ceramic vessels with painted images and inscriptions naming them as vessels for drinking chocolate, which they buried in elite tombs. There also was a cacao god.

Theobroma cacao is the modern scientific name for chocolate, and it is indeed fitting, for theobroma means “food of the gods.” The words “cacao” and “chocolate” come from indigenous American languages. “Chocolate” comes from Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec Empire. The word “cacao” was used by the ancient Maya, but the word likely originates with the Mije-Sokean language family.

Cacao grows as pods on the theobroma cacao tree. This plant likely originated in the Amazon Basin, but the earliest evidence of processing cacao is among the Olmec civilization in Mexico. Cacao—or traces of the compounds theobromine and caffeine—have been found in archaeological deposits from a number of civilizations, including the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec in Mexico and Guatemala, and the Ancestral Pueblo Culture at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico.

LACMA has many objects made to store, drink, or celebrate cacao. One tripod cylinder vessel portrays the birth of the first cacao tree from the body of a supernatural male figure. Next to this primordial tree is the lightning god K’awiil, who points toward the tree and its abundant cacao pods. In this myth, it likely is the lightning god who breaks open the earth so that the first cacao tree can emerge. On the other side of the vessel is a woman grinding something—likely cacao—on a stone metate (grinding stone). Next to her is a large bowl filled with tamales that perhaps (hopefully!) are covered with delicious mole, an ancient sauce made with chocolate that is a delicacy today in Mexico, here in Los Angeles, and across the world.

Other vessels portray cacao used as a drink. On one, an elite male figure—perhaps a Maya ruler—sits on a throne. Next to him is a cylinder vessel with foam coming from the top. This is a cacao drink that has been poured or stirred specifically to create this enticing foam. Beneath this man’s throne is a plate of—yet again—tamales covered with mole.

The word cacao—or kakaw—in Mayan hieroglyphs is spelled with the head, body, or fin of a fish. The word fish is kay in various Mayan languages, and this word was shortened to the syllable ka, which was doubled, and with an added wa syllable to spell ka-ka-wa, or kakaw. Because this word appeared so often in Mayan inscriptions, artists would abbreviate the word by putting one ka syllable but then two dots next to it to show it is doubled. On one vessel in the LACMA collection, the artist made those dots a part of the image, shown as if bubbles are coming out of the fish’s mouth.

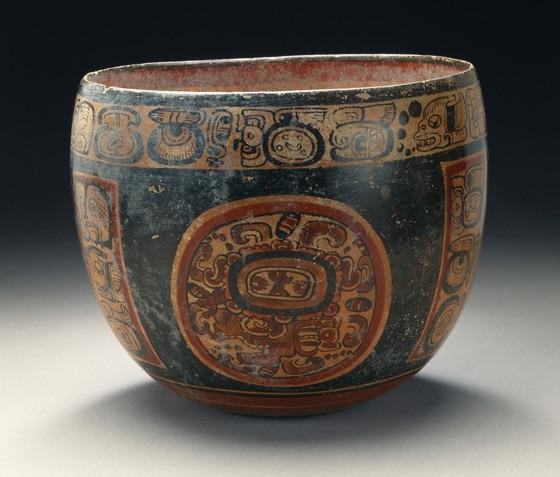

The word kakaw is inscribed on many Maya ceramic vessels. It appears most of the time as part of a dedication statement on a vessel’s upper rim identifying the vessel as a yuk’ib (drinking vessel) for cacao. The name of the vessel’s owner often appears in this inscription. Some, such as Drinking Cup for Cacao, are bowls that resemble the shape of a gourd, a traditional Maya drinking cup.

Kakaw also appears on lidded vessels that may have been used to store cacao beans or drink. On one lidded vessel in LACMA’s collection, the lid’s knob is the head of the cacao deity. Indeed, one has to touch him to gain access to the precious substance inside.

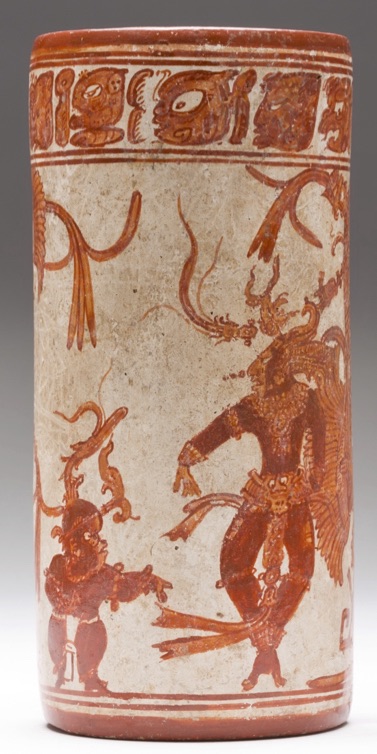

The kakaw glyph most commonly appears on Maya cylinder vessels from the Late Classic period (600–900 CE). These vessels often have beautifully painted images that portray scenes from Maya mythology and royal life. One vessel in the LACMA collection portrays a scene of the Maize God dancing, which he does to celebrate his rebirth and the renewal of the world. The owner of this vessel is identified as a royal woman.

To commemorate National Chocolate Day, I plan to celebrate the ancient Maya and other indigenous civilizations by eating some delicious chocolate—made from fair-trade cacao. For those of you who do the same on October 28, I hope you’ll appreciate those who first cultivated the cacao tree and developed exquisite foods and drinks that we still enjoy today.

View the vessels discussed in this post by visiting the Art of the Ancient Americas galleries and the exhibition Revealing Creation: The Science and Art of Ancient Maya Ceramics, on view in the Art of the Americas Building, Level 4.

For further reading:

Coe, Michael D. and Sophie D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate, 3rd edition. London: Thames and Hudson (2013).

Crown, Patricia L. and W. Jeffrey Hurst. Evidence of cacao use in the Prehispanic American Southwest.PNAS 106(7) 2110-2113 (2009).

Hall, Grant D., Stanley M. Tarka, Jr., W. Jeffrey Hurst, David Stuart and Richard E. W. Adams. Cacao Residues in Ancient Maya Vessels from Rio Azul, Guatemala. American Antiquity 55(1):138-143 (1990).

Kaufman, Terrence and Justeson, John. The History of the Word for Cacao in Ancient Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica, 18(2):193–237 (2007).

Martin, Simon. Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit of the Maize Tree and other Tales from the Underworld. In Chocolate in Mesoamerica: a Cultural History of Cacao, ed. Cameron McNeil, pp.154-183. Gainesville: University Press of Florida (2006).

McNeil, Cameron, ed. Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao. Gainesville: University Press of Florida (2006).