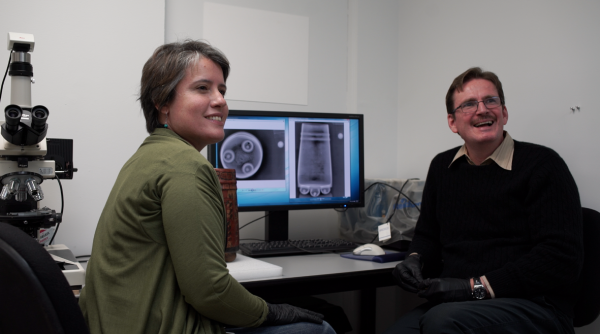

Currently on view in the Art of the Americas Building, Revealing Creation: The Science and Art of Ancient Maya Ceramics considers ancient Maya ceramic production as both art and science, informed by a multi-year collaborative research project by LACMA’s Conservation Center and the Art of the Ancient Americas Program. Unframed spoke with two key members of the research team: senior objects conservator John Hirx and associate curator Megan O’Neil, who curated the exhibition.

How did this project and collaboration come about?

Megan: It started on the curatorial side. Diana Magaloni, deputy director and director of the Art of the Ancient Americas Program, had worked for many years on collaborative projects in Mexico, particularly on painted Maya murals. That project put together art historians, archaeologists, scientists, and conservation scientists. So when she came to LACMA in 2014 it was her idea to start a collaboration with the Conservation Center on Maya ceramics.

When I started at LACMA in 2015, a couple of vessels had been chosen for this study. One of my first duties was to finish choosing them, and to organize the meetings in which we would meet to talk about the technical images produced by conservation photographer Yosi Pozeilov. When we first started, we didn’t know yet what our primary research questions were. We simply started looking at the objects and images and talking to each other about them, and we developed our questions along the way.

How did you select these particular objects?

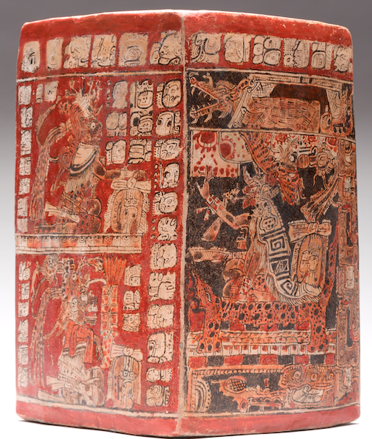

Megan: Some are our most important Maya ceramics, or unusual ones. There’s a square vessel that has a very important painted scene from Maya mythology on it. And so that was chosen. Others had been known about for a long time, and had been talked about by many scholars. We chose different objects we know are from different regions, to see what new imaging and analysis could tell us about them. We also chose a cluster of ones with stucco and post-fire painting, particularly because I was interested in cultural relationships between Central Mexico and the Maya region, and also because it would play into Diana’s specialty in mural painting. Most of the objects came from storage. It’s been nice to take objects out of storage and make them available for people to see.

What were some of the questions that you came up with?

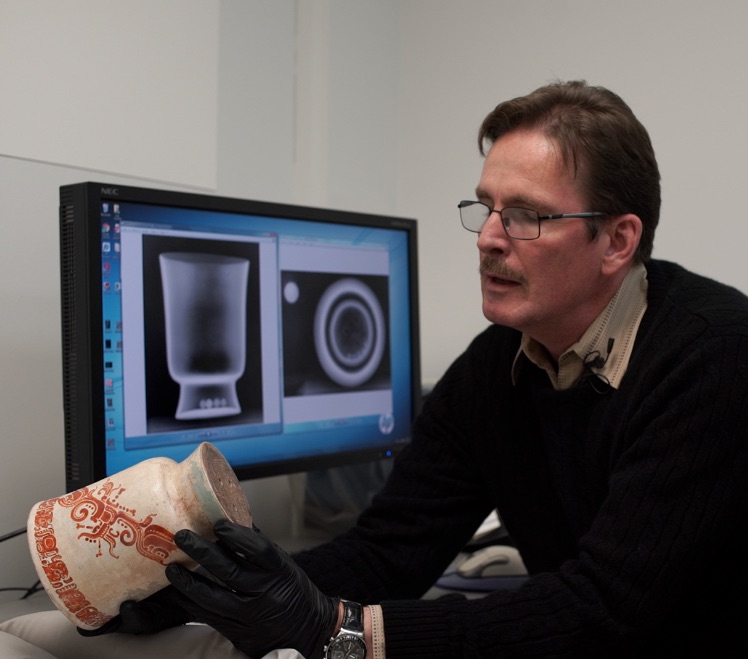

John: Well, we started off with conversations about ideas in the literature on the subject of the fabrication of these objects and questioned the validity of those ideas. If the ideas are true, what’s the evidence that supports those ideas, or what is the evidence actually telling us? Over the course of time, we did radiography, elemental analysis, and photographic imaging, and all of that data was used to put together information packages about individual objects.

I was trained as a potter before I became a conservator, and I’ve walked through the ancient Americas galleries for years. But I never spent time studying these particular pots. So we learned through radiography about who’s the master potter, who’s the master painter, and how they’re approaching problems they had to solve in terms of fabrication sequences.

It took a while to unravel some of the questions about manufacturing and surface decoration, and we are by no means at the bottom of all the questions. Once you’ve studied a pot, some of the answers from that study could be applied to a different pot. This is one way we answered a lot of really interesting questions.

How can you tell, from the radiography, who’s a master potter or painter?

John: For instance, there’s one pot in particular that’s just extremely well-crafted. I know from being a potter that there are criteria for making a vessel that helps it survive all the processes of making, drying, firing, and so on. You can extract a lot of information about how the potter or potters are working based on what you’re seeing in the radiographs. You can see even walls, pots that have all kinds of things in the walls, and walls with nothing extra added.

Megan: For this particular one, which we nicknamed the perfect pot, our scientists were able to measure the wall thickness and see how the thickness of the wall changed as the potter was shaping it—and what they discovered is that it was crafted with great care and precision.

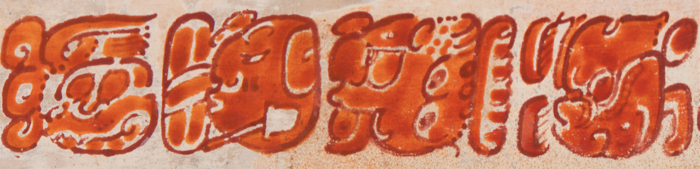

John: And this is the benefit of the digital world. We looked at things on large screens, with software to measure what you’re seeing—all of that supported a lot of hypotheses. And the palette of slip to make these paintings is extraordinary. It’s not just one white and one black and one red and one orange, it’s many many blacks, many many oranges, many many yellows, all to get just the right shades, the right colors. It’s basically like making a watercolor painting on a ceramic vessel. That’s extraordinary. Absolutely extraordinary.

For me, the perfect pot was kind of the portal into these ceramics. The pot has glyphs painted on it. I looked at these glyphs under the microscope and realized that the person who painted the glyphs used a pointed stylus to clean every edge, so every glyph is perfect. It’s not something you would see with the naked eye, it’s not something you’d normally look for. That level of craftsmanship kept translating through that vessel. Whether it’s the walls, the slip—this person wanted the most perfect pot that they could achieve. And they certainly achieved it. It’s just unbelievable. There was a certain level of ceramic achievement in these vessels that I had not recognized prior to this project.

How did your individual area of expertise contribute to the project?

Megan: There’s so much complexity in all of this. You have to know the iconography, the chemistry, the clay, the materials available to them, firing… We’d have a meeting, we would make progress, and we often ended those meetings with a question, and we’d all run to our respective stacks of literature then come back to the table. And then we would say, well, this is what someone says about what they’re putting in the clay to make it withstand the firing. Or, this is what someone suggests is in the slip, or something like that. John also would often have insights in his car—there’s a value to commuting in Los Angeles.

John: We could not have gotten to the bottom of a lot of these answers if we did not have the group assembled as it was, with each person’s different perspective. Different conversations would be happening and I’d hear something and these bits and pieces of information were fodder to think about what was happening with this vessel and why. No one person would have been able to extract all the information out of the wares.

Megan: And it also seems like John’s expertise in ceramics from other areas of the world helps him with looking at Maya materials.

John: Absolutely.

Megan: He would often bring up his studies of Islamic tiles and say this was what we found when we studied that; could that apply here? Maybe yes, maybe no, but that kind of questioning is similar to what we do in comparative art history or anthropology. We have more information from the Egyptians or the Greeks, for example, because they recorded more information that survives; can that information or those questions help us with interpreting—or at least raising questions about—ancient Maya artworks and civilization?

John, you mentioned your training in ceramics. What made you want to go into conservation?

John: I couldn’t see myself sitting making coffee mugs by the hundreds of thousands. I wanted to be in a discipline where there is never an end to learning. You can never know enough as a conservator; it’s impossible. At the time that I was thinking about career paths, the Italians were working on the cleaning of the Last Supper. And I thought, hmmm. A conservator has to pull together studio, art history, science, and engineering, all to make this conservator package. And that to me was very interesting.

Did your background as a potter inform the way you approached this project?

John: A lot. How something is made is just part of our training as conservators, so I’m always disassembling an object and putting it together again in my mind. But if I hadn’t been trained as a potter, I wouldn’t have been able to answer the curators’ questions. You have to have worked in all these different temperatures and color palettes, and to have studied ceramics in museum collections.

So-and-so says it’s done this way, but is that person a potter? No, it’s just someone throwing out an idea. They’re not really interpreting the evidence correctly. For the questions we were asking, looking at a pot didn’t give you all the answers. You need analytical techniques.

So the historians would go back to the literature and come back to say, well, so-and-so says this, and you’re saying this. I had to justify a lot of my answers. I had to sit and think, this is how I would do it. Does it match what I’m seeing here, or did they go about it a different way?

Can you tell us about an example of that?

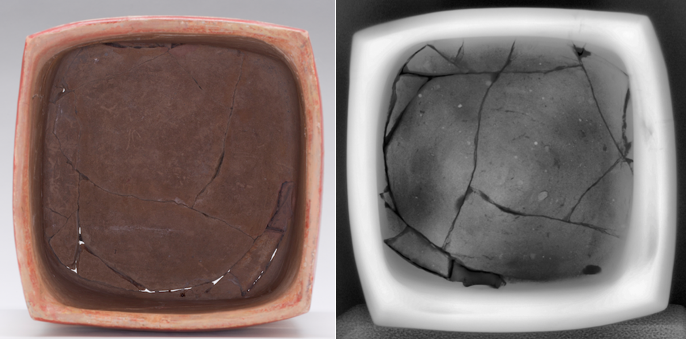

Megan: I remember the first time we met about the square vessel (the “Vase of the 11 Gods”). I think it was just after the elemental analysis, and the conservators and conservation scientists all said they didn’t like it, because it has a lot of modern repaint that was applied before it came to LACMA. So we thought, should we have picked another vessel? Can we still learn something from it? We had to break through that barrier and figure out what we could learn from radiographs as well as from visual and tactile analysis.

John: This square pot really threw me for a loop. It took me a long time to understand how it was made, because it wasn’t made the way I would make it. Usually, things that are round are made with some sort of a wheel or a turning operation. Things that are flat are usually made with slabs.

Megan: That was the assumption about this vessel for many years.

John: But this was made with coils, the way many other pots are made. It came about through all of Megan’s work in the end, this connection between culture and clayworking. The circular movement—the spiral—is important, including in the making of this square pot. This person, whoever made this, had to square something that was round. That was the struggle of this vessel, because everything I looked at, the radiographs and the pot, made me wonder, why is this pot so weird? Because the cosmic or cultural mind altered one way of working to make something that’s round in a square shape. Eventually, I started to get around to that idea because my ceramics professor threw round bowls, then she would smack them into squares. It’s called thrown and altered. It was her generation of clayworking—throwing a vessel, then doing something to deliberately alter it, to break a barrier between craft and art.

And once we realized it was coiled, we began to notice more evidence for that. This pot we’re talking about, they didn’t square the inside. Evidence for the coil is all over this thing. But never in a million years would I have expected it to be there. If we didn’t have the group assembled, I would never have questioned the vessel; it wasn’t something on my radar to question. Once it got on my radar, I thought, why does it look this way? That was when car epiphanies usually took over.

Will the project continue with other vessels?

Megan: As John said, we still have some questions with the 15 vases, and we want to publish the results of our research. But what else do we need to answer some of these questions? Do we need to look at other vessels in the collection? Yes, most likely. Do we need to look at vessels in Guatemala’s national collection, or Mexico’s national collection? Yes, we certainly hope so. We’re shaping what we can do now, continuing with more discussions, and figuring out our future research strategies.

What do you wish for visitors to take away from the show?

John: Once you have a look at those vessels, hopefully you won’t just walk past a pot anymore.

Megan: What I wanted to do for this exhibition was to have many ways for people to look at this material. People with interest in art—particularly in making art— can enter in one way, people with an interest in science, or culture, or archaeology can enter in other ways. The interdisciplinary nature of the project has been fun and rewarding; everybody’s contributing and everybody’s learning. This kind of project not only helps us learn more about the objects and the culture and the artists, but it also gives us more ways to reach out to our audiences. More people can understand Maya ceramics from different perspectives. It’s also important for me to balance this new knowledge—not necessarily privileging Western science, but using it to illuminate ancient Maya technologies.

Revealing Creation is ongoing in the Art of the Americas Building.