For more than a century, visual artists have been inspired to expand their artistic practices by engaging in compelling collaborations with the ballet, theater, and opera. This impulse has given us the historic productions of the Ballets Russes under the direction of the Russian Serge Diaghilev in the teens and 1920s; the avant-garde approaches of Oskar Schlemmer and Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus in the 1920s and early 1930s; and the experimental cooperation between artists, composers, and dancers at Black Mountain College in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. More recently, contemporary artists have partnered with directors of international ballet and opera companies to create memorable interpretations of theatrical works. Chagall was at the forefront of interdisciplinary efforts among modern artists in creating inventive visual environments for the stage. Working with theatrical companies and opera houses in Russia, Mexico, New York, and Paris, Chagall created fantastical and innovative designs, marking an early chapter in the history of artists who have engaged in similar collaborations and immeasurably enriching the history of modern art.

Chagall’s lifelong engagement with the stage began in 1911, when he worked with Léon Bakst—Russian painter, scenic and costume designer, and Chagall’s teacher when he studied in St. Petersburg—on set designs for the Ballets Russes. Inspired by Richard Wagner’s theory of the gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), Diaghilev’s company revolutionized ballet by envisioning the medium as a vehicle for the convergence of music, dance, and art. In the early years of the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev frequently collaborated with painters; his success was primarily due to his ability to identify and bring together the most creative artists of his day. He reached outside of the circle of Russian artists with whom he had established the Ballets Russes’s reputation and made alliances with those based in Western Europe. Combining Russian and Western traditions with a healthy dose of modernism, the company thrilled and shocked audiences with its powerful fusion of choreography, music, design, and dance. By the time of his death in 1929, Diaghilev had engaged virtually every prominent artist in Paris to work as a designer for his company—among them Natalia Goncharova, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Joan Miró—making the Ballets Russes stage one of the chief venues for the development and exhibition of modernism.

Chagall moved to Paris in 1911, only a few months after the Ballets Russes premiered there. During Chagall’s four-year stay, he immersed himself in the international avant-garde world of artists, poets, writers, dancers, and musicians, and associated with fellow expatriate artists—among them Diaghilev and Bakst. Although Diaghilev never offered Chagall a commission, the artist’s connection to the theater was deeply linked to the Ballets Russes, and as a young artist the opportunity to work with Bakst and see famed Russian dancers such as Vaslav Nijinsky perform left a profound impression that helped to fuel his passionate engagement with music and dance.

Chagall was forced to return to his native Russia in 1914 due to the outbreak of World War I. In the years leading up to and immediately following the Russian Revolution of 1917, he played an important role within the avant-garde, and began to explore Jewish culture through the theater. In 1920 Chagall received his most important opportunity at that point in his career when Alexei Granovsky, director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater, hired him to create the sets and costumes for the inaugural production of An Evening of Sholem Aleichem, which premiered in 1921. A theater for the proletariat, the company offered daring productions of traditional and contemporary Yiddish dramas, transformed to accord with the ideas of the Russian Revolution. As evidenced in Chagall’s designs, in its early years the Yiddish theater cultivated an avant-garde approach which combined strikingly reductive, constructivist-inspired sets with an exaggerated, almost expressionistic acting style.

Chagall’s best known artistic contribution to the Jewish theater are the painted murals he created in 1920, which included four canvasses representing the arts—Music, Dance, Drama, and Literature, and a monumental work titled Introduction to the Jewish Theater. Covering the walls of the auditorium, Chagall’s work transformed the space into an immersive pictorial environment. Chagall’s work for the Moscow State Jewish Theater revealed his talent to create scenic space that he would continue to develop in his later theatrical productions.

Chagall left Russia in 1922, and following an 18-month stay in Berlin, he arrived back in Paris where he produced an extensive body of work—paintings, drawings, and prints most often employing a personal visual vocabulary filled with images from his native Russia, Yiddish folk tales, and drawing inspiration from the Old Testament. However, the Nazi occupation of France made it increasingly difficult for Chagall and his family to remain there safely, and thanks to an invitation from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and with the help of Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee, he and his wife Bella were able to emigrate to the United States, where they would remain for the duration of the war. The exile culture in New York offered the artist a heady mix of refugee intellectuals who had been displaced by the spread of Nazism in Europe, and Chagall found a receptive environment for his work there.

Early in his New York exile, the Ballet Theatre of New York (now the American Ballet Theatre) commissioned Chagall to design the scenery and costumes for Aleko, a new ballet based on an 1824 poem by Alexander Pushkin and set to Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Trio in A Minor. The ballet was choreographed by Léonide Massine, a fellow émigré and former member of the Ballets Russes, with Alicia Markova and George Skibine dancing the lead roles. Aleko was meant to debut in New York, but union rules would have prevented Chagall from painting the backdrops himself, so he, his wife Bella, and the Ballet Theatre completed work on the production in Mexico. Bella provided integral support—she sourced materials from Mexican markets, and supervised the fabrication of the costumes. Chagall hand-painted the Aleko costumes and backdrops, which have retained their vivid colors after more than 70 years. The artist drew inspiration from Mexican styles of dress and traditional textile motifs, as well as from the music, poetry, and art of his native Russia. Chagall’s work premiered at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City on September 8, 1942, before opening at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York a month later. In the summer of 1943 the ballet was performed at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

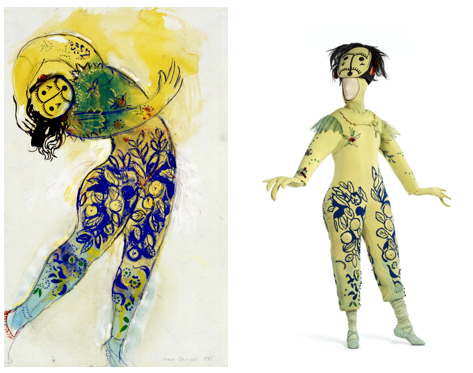

The success of Chagall’s Aleko led to his second commission from the Ballet Theatre. In 1945, the performing arts impresario Sol Hurok decided to restage Igor Stravinsky’s iconic ballet The Firebird, which had premiered in Paris in 1910 at the Ballets Russes. Chagall re-envisioned the stage curtain, sets, and costumes for the ballet, which debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on October 24, 1945 and was performed in Los Angeles in 1946. The more than 80 costumes Chagall made for the ballet were his most inventive to date, particularly those for the fantastical animals and monsters that abound in the ballet’s narrative. Working with his daughter, Ida—who was integral to the process—Chagall employed new materials and fabrication techniques, including a combination of diaphanous and heavy, richly colored fabrics, collage-like appliqués, and intricate embroidery.

In 1949 Hurok sold Chagall’s production of The Firebird to George Balanchine, co-founder and artistic director of the New York City Ballet. Balanchine revised the choreography and in 1970 asked Barbara Karinska to reconstruct Chagall’s costumes, which she did by closely referencing the artist’s sketches and with his guidance and approval. This production of The Firebird remains in the company’s repertoire, performed as recently as the 2016 season of the New York City Ballet.

Shortly after Chagall’s premiere of The Firebird and the end of World War II, the artist returned to France, where he lived until his death in 1985. In 1956 the Paris Opera Ballet commissioned him to design new sets and costumes for Maurice Ravel’s ballet Daphnis and Chloe, which was based on a story attributed to the second-century Greek poet Longus. The motifs and color palette of blues and earthy ochers of Chagall’s stage designs were inspired by two trips he took to Greece in 1952 and 1954, which is the setting for the ballet’s narrative. Chagall’s production of Daphnis and Chloe was choreographed by George Skibine (who also danced the role of Daphnis), and premiered at the Paris Opera on June 3, 1959. Chagall worked closely with Skibine and the other dancers to harmonize his costumes with their movements and gestures. His designs incorporated shimmering layered appliqués on sheer fabric, and he painted bold swaths of color directly onto the costumes while the dancers were wearing them in order to emphasize the fluid lines and dynamism of the dance. Chagall envisioned the dancers as mobile elements of his paintings, mirroring the figures he depicted in flight across his backdrops.

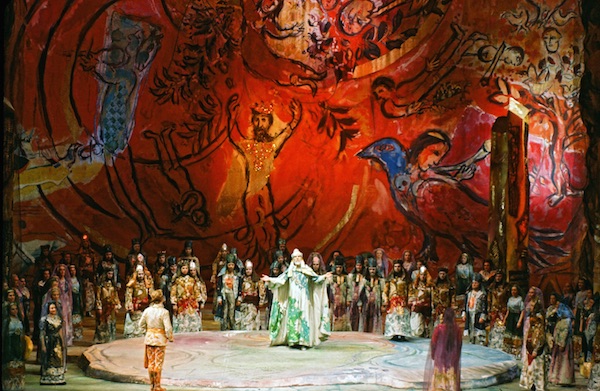

Chagall’s last stage adventure would be to create sets and costumes for a new production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera House for its inaugural season at Lincoln Center in New York in February 1967. Widely praised, this was Chagall’s only work for opera. He spent three years designing the 14 sets and 121 costumes, working in close collaboration with members of the Met’s costume and set design workshops. Challenged by the complexity of the opera’s numerous scene changes, stage machinery, and the large number of singers, Chagall conceived aesthetic solutions that emphasized strong color contrasts and striking geometric forms to construct scenic space and communicate the dramatic narrative.

Whimsical and highly imaginative creatures such as those Chagall created for Aleko and The Firebird—as well as in paintings throughout his oeuvre—populated the artist’s production of The Magic Flute. He sculpted each costume by layering richly dyed textiles with colorful fabrics and embroidered lines to highlight form and movement.

Chagall’s collaboration with the Metropolitan Opera was a fitting conclusion to his 50-year engagement with painting, music, and dance that sought to embody the principle of gesamtkunstwerk that had inspired him as a young man. Notably, Chagall set the stage for future artistic collaborations with music and dance. Today it is more commonplace for opera, symphonies, and dance companies to work with visual artists, and Mozart’s The Magic Flute in particular has attracted the creative attention of artists. Chagall was one of the first painters to design for Mozart’s masterpiece, and the opera has since provided inspiration for a diverse range of artists—David Hockney, Jun Kaneko, Maurice Sendak, William Kentridge, Jaume Plensa, and Frances Stark among them. Such collaborations bear witness to the lasting impression made by Chagall’s artistic engagement with music. Indeed, the artist’s enduring involvement with the stage—from his earliest work with the Jewish Theater in Moscow, to his collaborations with the ballet companies in New York and Paris, and finally with the Metropolitan Opera—has continued to prove influential, decades after his death.

Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage is now on view in the Resnick Pavilion through January 7, 2018.