Next year, part of LACMA’s collection will fly across the vast Pacific to mainland China for a special exhibition, Forces of Nature: Ancient Maya Arts from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, curated by Dr. Megan E. O’Neil, associate curator of the art of the ancient Americas at LACMA. Representing around 200 artifacts from the ancient Americas, Forces of Nature is a singular exhibition, detailing the relationships that the ancient Maya had with the natural and supernatural realms. The exhibition also showcases some objects from neighboring cultures and those that thrived before and after the Classic-period Maya, while the catalogue features a discussion on how contemporary Maya practices relate to those of the past. This exhibition thus encompasses nearly three millennia of Mesoamerican history, from the Olmecs to the contemporary Maya. After a year of touring China, the exhibition will return to LACMA for display in Los Angeles.

In the summer of 2016, I was a Mellon Fellow in the Art of the Ancient Americas at LACMA as part of the UCLA-LACMA Mellon initiative. Toward the end of my tenure as a summer fellow, Megan invited me to stay on as the research assistant for Forces of Nature, and we worked closely together over the course of the following year. My job comprised of a number of vital experiences for an art history graduate student including object viewings, interdisciplinary research, and catalogue writing. At the onset, exhibition planning required us to survey the collection and view potential objects in LACMA storage. After numerous viewings (which included observing, photographing, and measuring all the pieces) and conservation assessments, Megan created a short list of objects to use in the exhibition, though this altered slightly with further examinations that determined whether or not objects could travel safely to and from China.

Once the checklist had been established, the real probing began. For each object, we completed extensive research to hone in on possible attributions for cultures, geographic origins, and periods of manufacture. No easy feat! What is so unique about this project and working with Megan is that I was encouraged to explore objects in an interdisciplinary fashion, looking at archaeological reports, ethnographies, material analyses, and texts on iconography. The interdisciplinary approach and rigor with which the objects are addressed makes this exhibition intellectually rich. Following the research, Megan and I wrote a number of texts to accompany sections of the exhibition that collated information on individual objects. I was given permission to pick sections that interested me, so I wrote on topics like agricultural harvest, animals, and the role of hallucinogens in art and ritual.

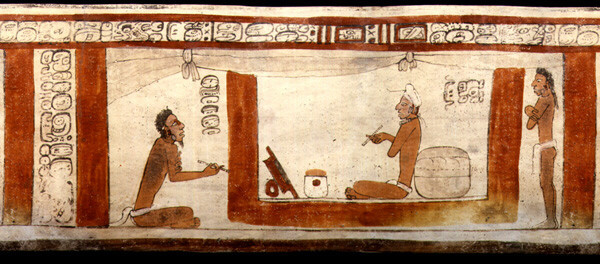

To provide an example of how our interdisciplinary research produces the actual museum texts, I will briefly highlight the section on tobacco and enema usage among the Maya. In the exhibition, there is a set of Classic-period Maya bottles that portray two aged, wrinkled faces, especially puckered because they are shown in the midst of inhaling tobacco. Relatively recently, residue analysis on a similarly sized Maya bottle from the Library of Congress revealed traces of nicotine on the inside. The LACMA bottles contain dark stains inside, likely an analogous tobacco residue, though it has not yet been tested. Based on iconographic studies, the faces of the bottles could represent God L, a toothless, aged deity who is typically depicted smoking a cigar and is often associated with tobacco use.

The ancient Maya and other Mesoamerican groups consumed tobacco either alone or mixed with hallucinogens to induce trances or provide healing. Given the close connection between our bottles and other residue and iconographical analyses, we can make strong claims about the function and cultural context of these objects and relay that information in the catalogue and didactics that will appear in the museums in China.

Overall, this experience taught me a great deal about how to produce a traveling exhibition in an expedited timeframe. Apart from learning the jargon of the museum world, I was also able to strengthen my abilities as a researcher and writer. It expanded my knowledge of Mesoamerica, both geographically and chronologically, and allowed me to explore my interests in the Maya outside of the classroom. Now that my position has come to an end, it will be a treat to see how the exhibition is received and how it impacts visitors halfway across the globe.

I would like to extend my gratitude to Megan O’Neil for inviting me to be a part of the enriching Forces of Nature project.

Anthony J. Meyer is a PhD student in the Department of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he specializes in the study of indigenous arts as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow of Distinction. His current research centers on Imperial Aztec artistic practice and early modern transatlantic exchange, probing the role of indigenous bodies and sculptures in both Mexican and 16th-/17th-century European spaces.

FOR FURTHER READING

Loughmiller-Cardinal, Jennifer A. and Dmitri Zagorevski. “Maya Flasks: The ‘Home’ of Tobacco and Godly Substances.” Ancient Mesoamerica 27 (2016): 1–11.

Miller, Mary M. and Megan E. O’Neil. Maya Art and Architecture. 2nd edition. World of Art series. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2014.

Smet, Peter A. G. M. de. Ritual Enemas and Snuffs in the Americas. Dordrecht: Foris Publications, 1985.